Email all work for the course to me at [email protected]

NO KNOWLEDGE OF FRENCH IS REQUIRED FOR THIS COURSE. A Desire to Learn Is Required for this Course.

Proust is often funny, really humorous:

“Everybody calls ‘clear’ those ideas which have the same degree of confusion as his own.”

Let's listen to the most famous passage in the novel:

Remembrance Of Things Past by Marcel Proust / Tom Hiddleston / Words and Music: Memory

Le petites madeleines / The little madeleines (a madeleine is a kind of cookie taken with tea)

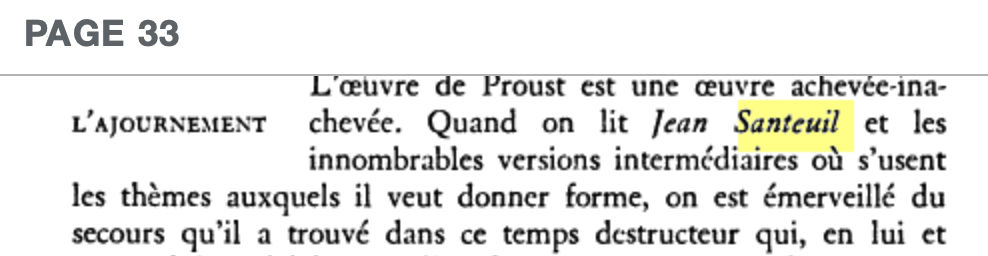

Now let's LISTEN to John Rowe's audiorecording on Audible.com

Some Questions:

1. What does "lost time" mean in the title In Search of Lost Time?

What is the final word of the novel? Can you guess? Time!

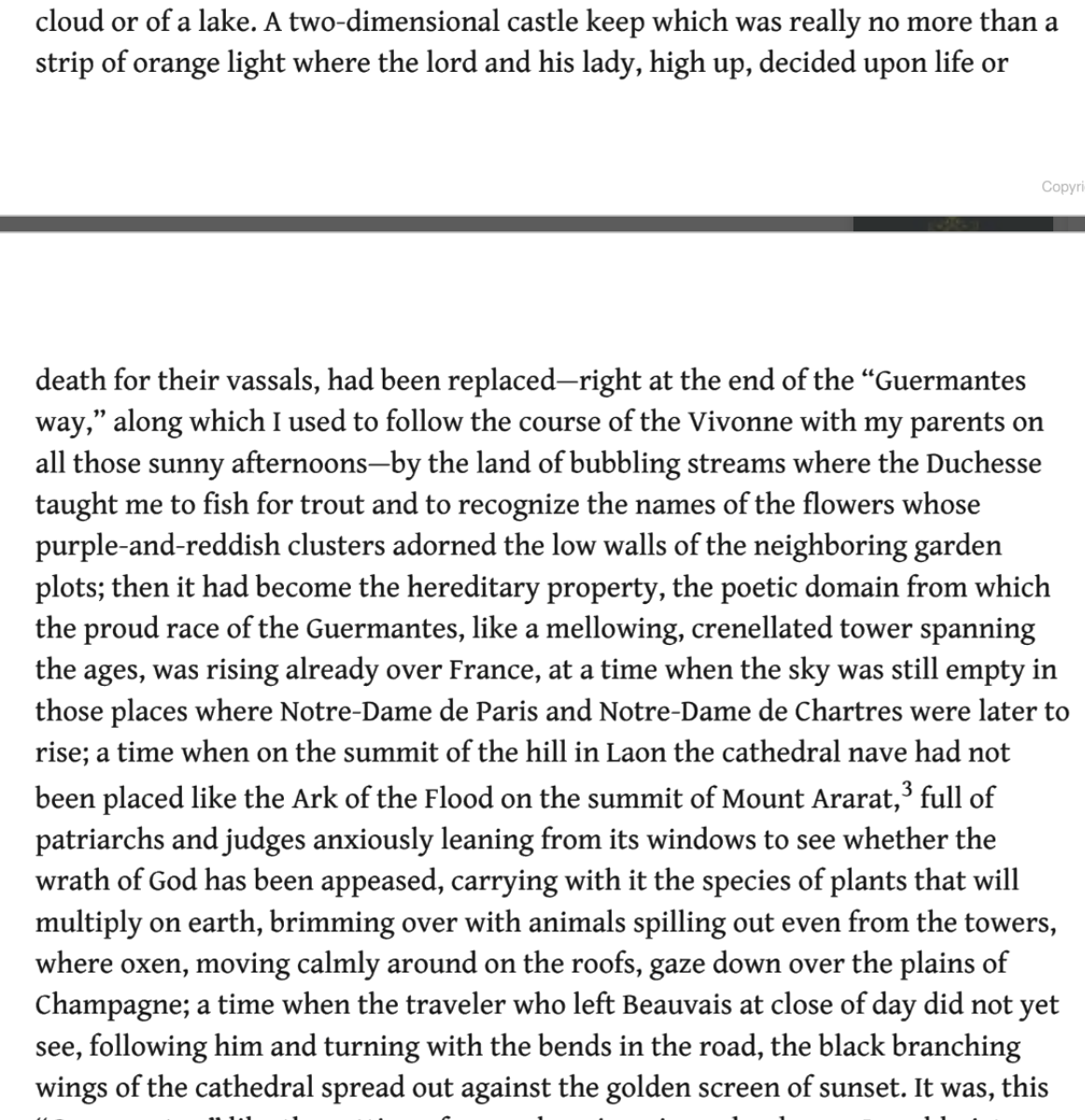

A character in Proust's novel, namely, the narrator says:

"And if, after so many years and so much lost time, I felt the stirring of this vital pool within humanity even in international relationships, had I not apprehended it at the very beginning of my life when I read one of Bergotte’s novels in the Combray garden and even if today I turn those forgotten pages, and see the schemes of a wicked character, I

cannot lay down the book until I assure myself, by skipping a hundred pages,

that towards the end the villain is duly humiliated and lives long enough to know

that his sinister purposes have been foiled. For I could no longer recall what

happened to the characters, in that respect not unlike those who will be seen this

afternoon at Mme de Guermantes’, the past life of whom, at all events of many

of them, is as shadowy as though I had read of them in a half-forgotten novel."

This is Proust recalling a passage in Swann's Way, the first novel, toward the end of Finding Time Again (aka Time Regained aka Time Recaptured), the last of seven novels that make up the Recherche.

Or you could follow an analogy or other kind of comparison such "as though." Or butterflies as metaphor and simile in Flaubert's Madame Bovary.

The novel as a palimpsest of the narrator's experiences, memories of them, involutary memories, forgotten memories, and so on.

The smallest facts, the most trivial happenings, are only the outward signs of an idea which has to be elucidated and which often conceals other ideas, like a palimpsest.

--Proust, The Guermantes Way

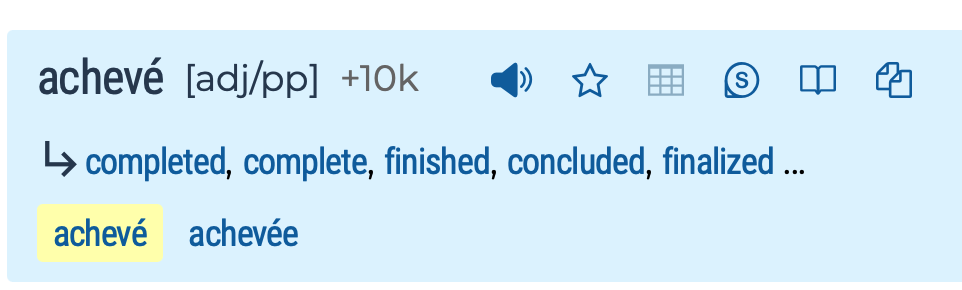

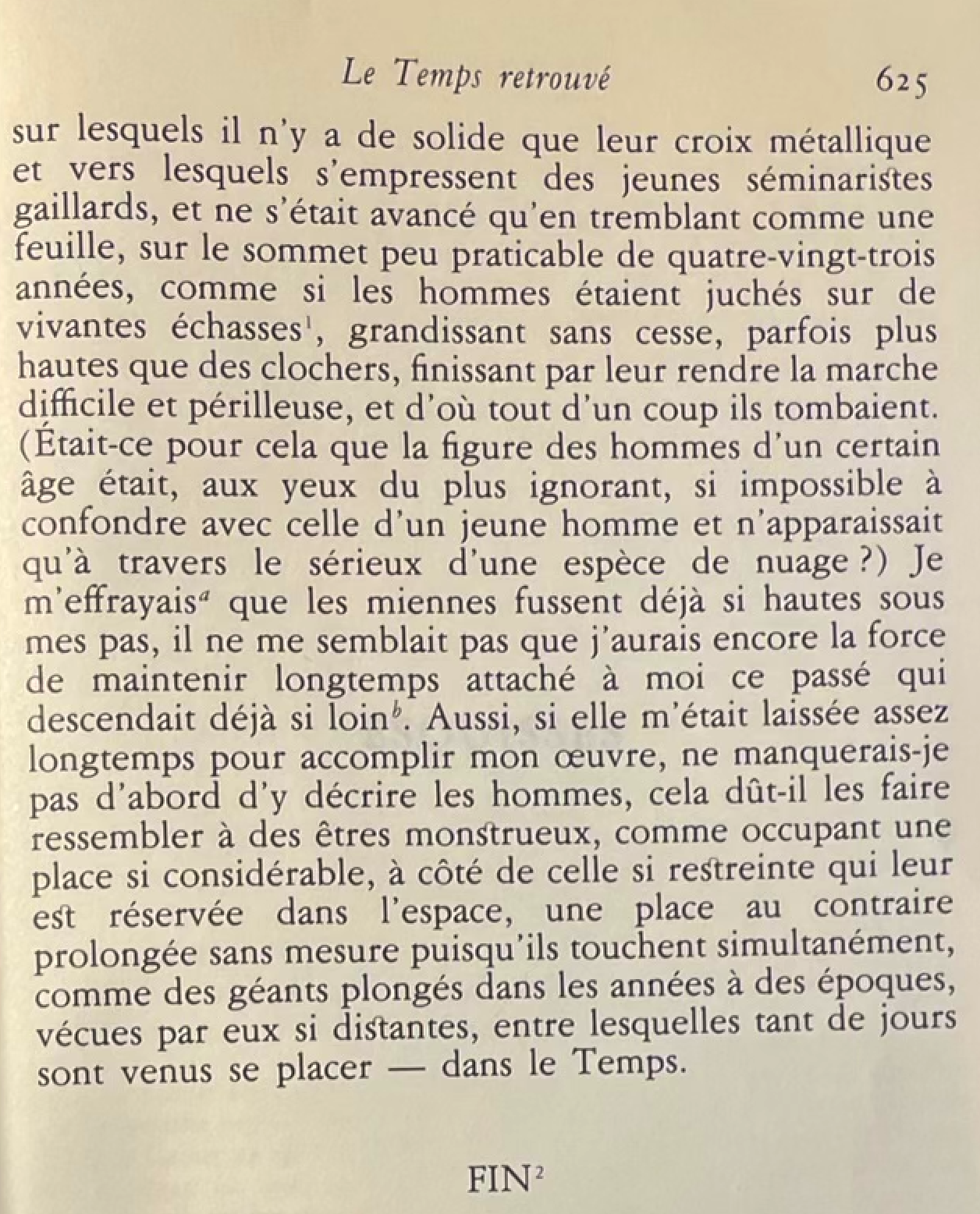

Here is the last sentence of the novel:

Therefore, if enough time was left to me to complete my work, my first concern would be to describe the people, even at the risk of making them colossal and unnatural creatures as occupying a place in far larger than the very limited one reserved for them in space, a place in fact almost infinitely extended, since they are in simultaneous contact, like giants immersed in the years, with such distant periods of their lives, they have lived through—between which so many days have taken their place—in Time.

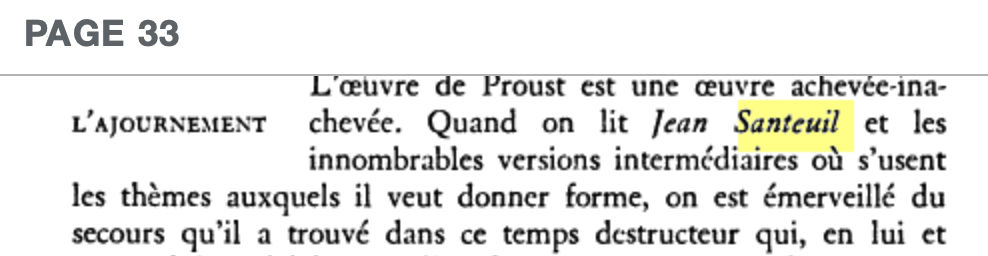

2. What does a "complete incomplete" novel mean?

Proust on the incompleteness of the work of art in The Prisoner

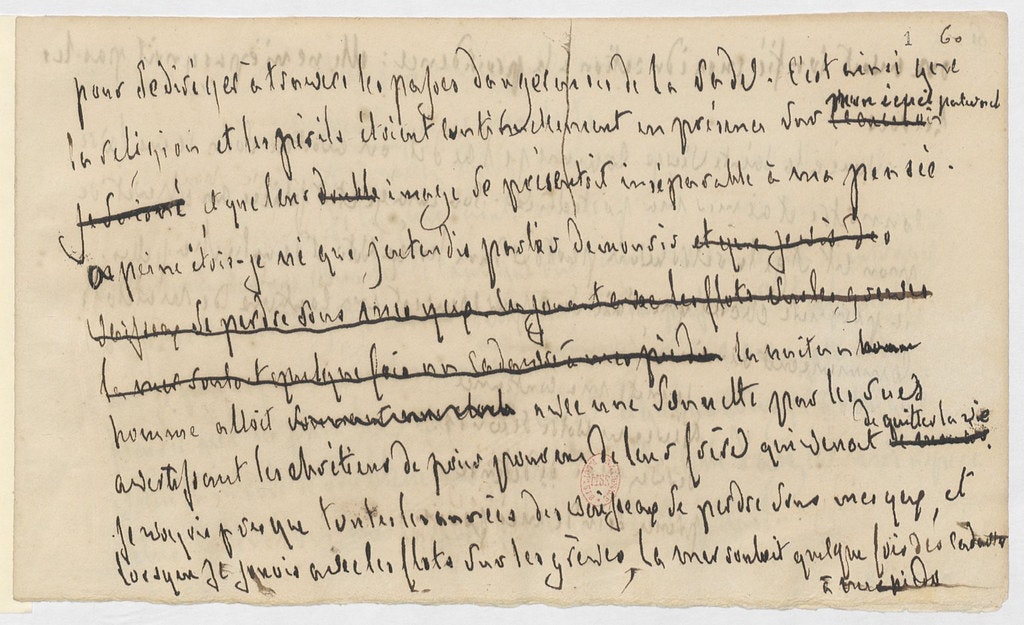

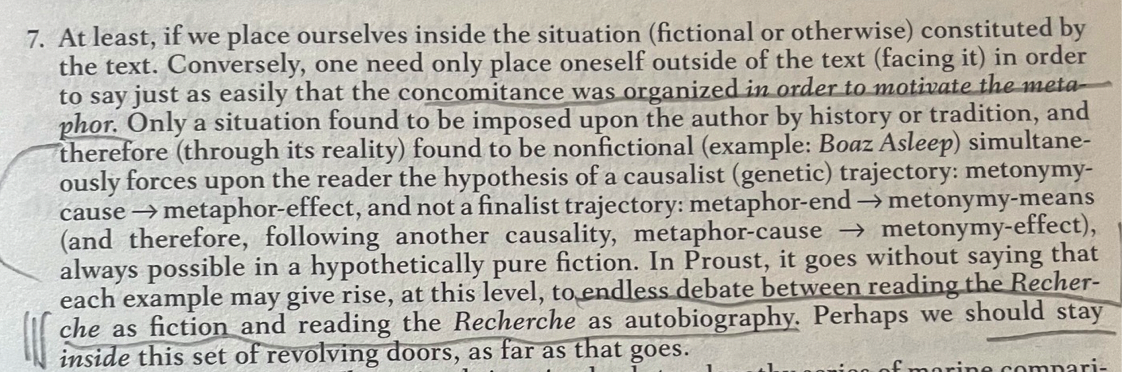

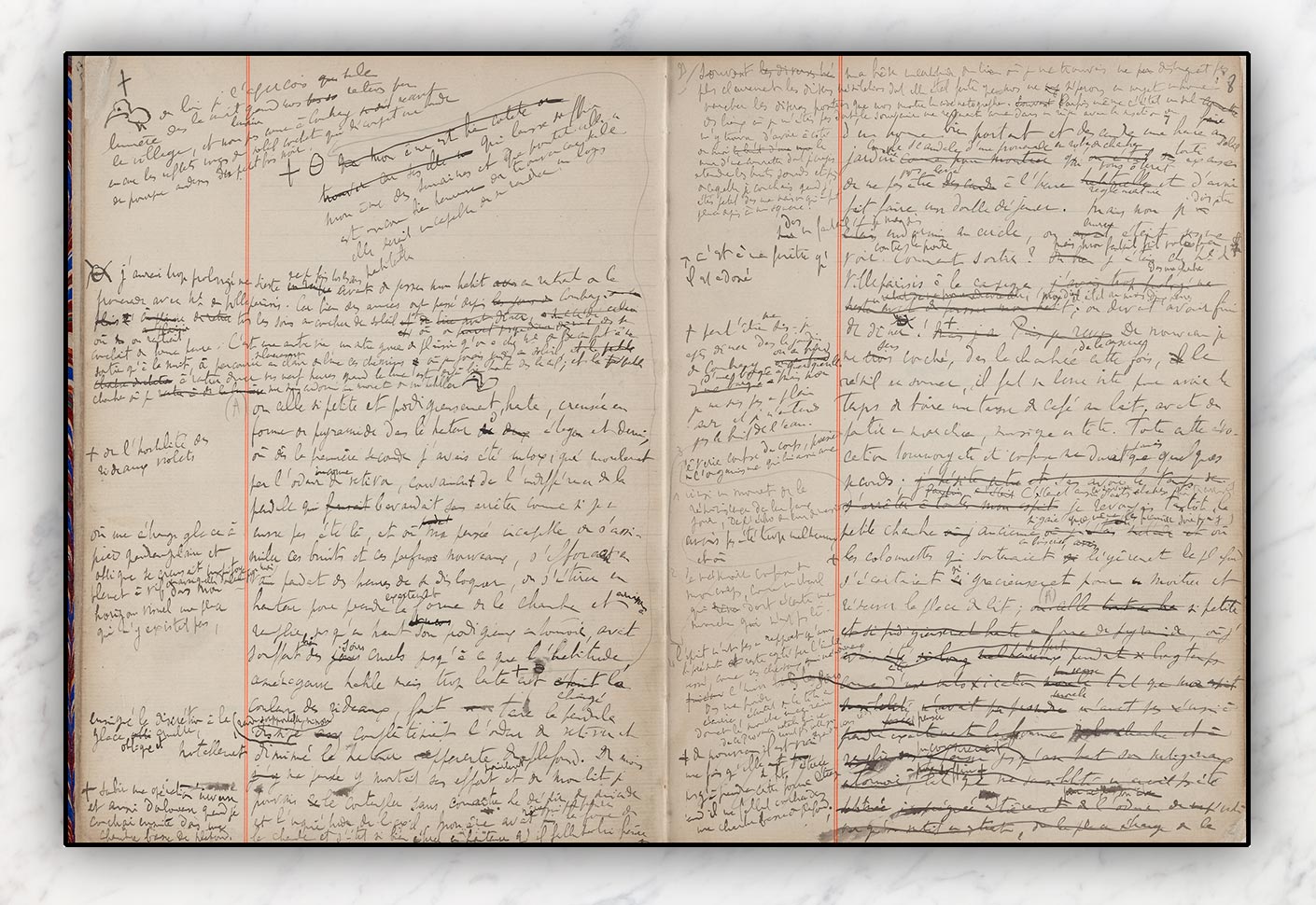

Here's another question: Can you finish Proust's novel? And here's yet another: Is the novel complete? Did Proust finish it? (No. He died before he could.) Would Proust have ever finished it? Galley Sheets of Swann's Way.

Proust on the incompleteness of the work of art

Thus, not only is the Recherche, as Blanchot says, a "completed-incompleted" work, but its very reading is completed in completion, forever in suspense, forever "to be taken up again," since the object of that reading is constantly thrown into a dizzy rotation."

--Gérard Genette, "Proust's Palimpsest," Figures of Literary Discourse, p. 222

What is a palimpsest?

Palimpsest / Die Wand (The Wall)

Leo Bersani, “Proust and the Art of Incompletion.” in Balzac to Beckett: Center and Circumference in French Fiction.New York: Oxford UP, 1970. 192–239.

Thomas De Quincey, The Palimpsest of the Human Brain in Suspiria de Profundis

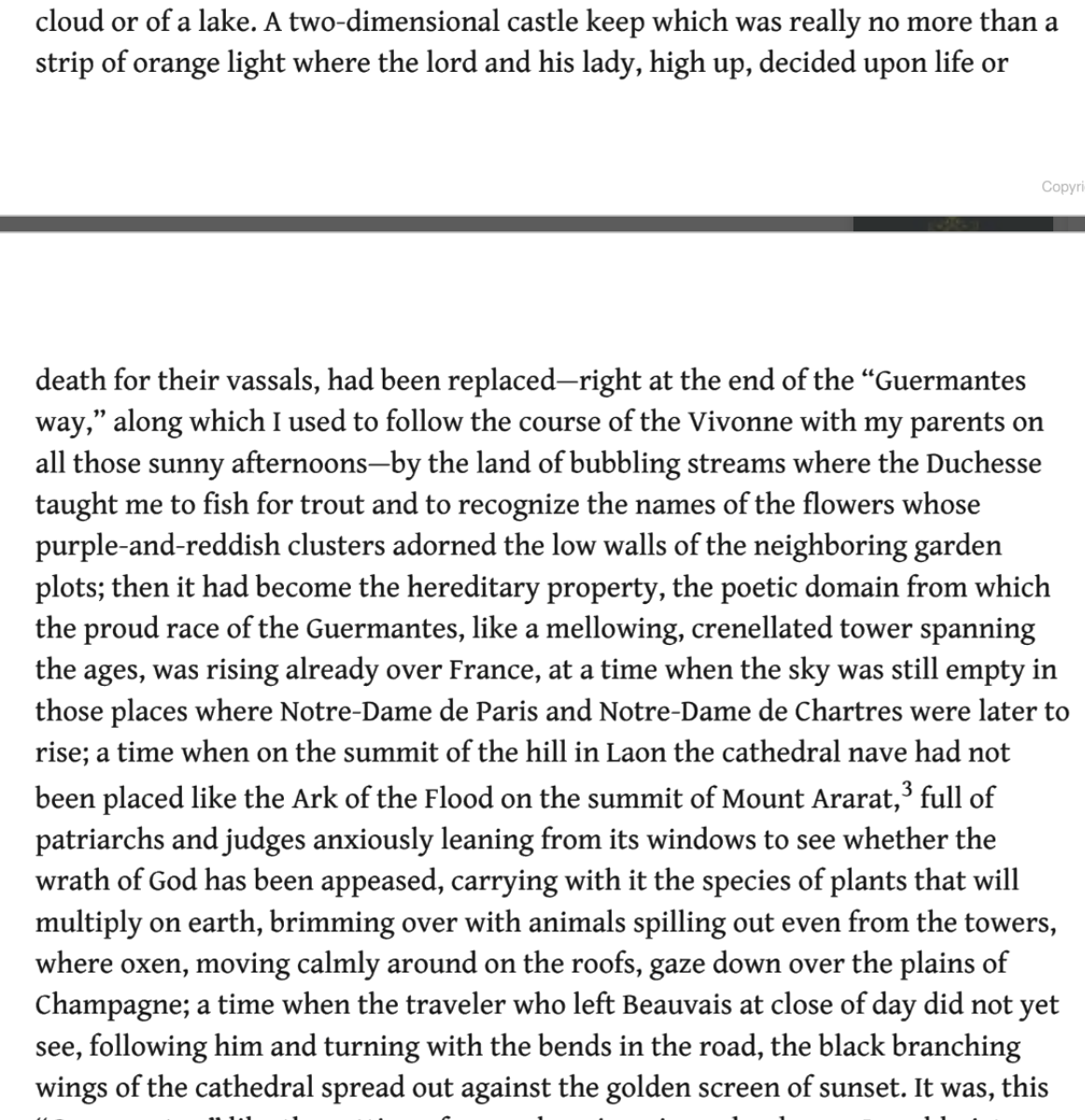

Who is Marcel Proust, what is In Search of Lost Time like, and how should we read it? Here's what Proust's narrator says in the Finding Time Again:

It is only through a custom which owes its origin to the insincere language of prefaces and dedications that a writer says “my reader.” In reality, every reader, as he reads, is the reader of himself. The work of the writer is only a sort of optic instrument which he offers to the reader so that he may discern in the book what he would probably not have seen in

himself. The recognition of himself in the book by the reader is the proof of its

truth and vice-versa, at least in a certain measure, the difference between the two

texts being often less attributable to the author than to the reader. Further, a book

may be too learned, too obscure for the simple reader, and thus be only offering

him a blurred glass with which he cannot read. But other peculiarities (like

inversion) might make it necessary for the reader to read in a certain way in

order to read well; the author must not take offence at that but must, on the

contrary, leave the reader the greatest liberty and say to him: “Try whether you

see better with this, with that, or with another glass.”

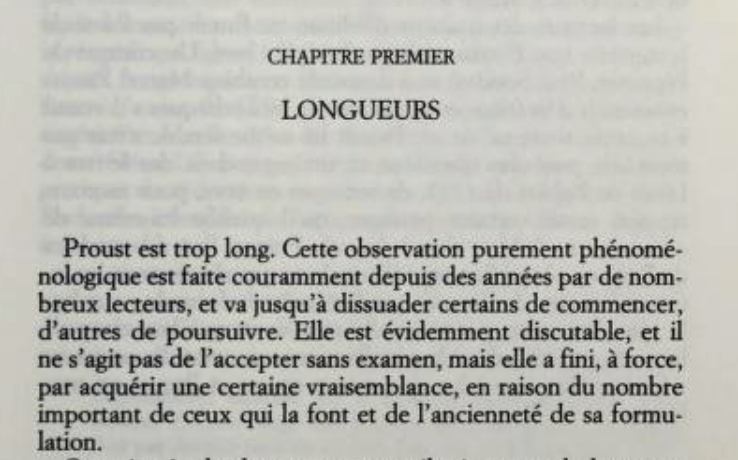

3. Why is Proust so long?

The use of three options Proust's author gives the reader in that last sentence above--

"with this, with that, or with another glass”

--is very Proustian. (However, notice that in this example, Proust doesn't differentiate between the three glasses.)

Proust uses phrases like "or perhaps" several times in one sentence.

"Since [Leo] Spitzer, critics have often noted the frequency of those

modalizing locutions (perhaps, undoubtedly, as if, seem, appear). . . .

When the narrative offers us, introduced by three perhaps's, three explanations to

choose from for the brutality with which Charlus answers Mme.

de Gallardon, or when the silence of the elevator operator at

Balbec is ascribed with no preference to eight possible causes,

we are not in fact any more "informed" . . . .

--Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse, p. 203

Look for syntatic repetition; Proust will repeat the same words at the beginning. “Perhaps it was because . . . . ; or perhaps . . . . ; or perhaps . . . ; or perhaps . . . . These are syntatic patterns any writer knows. The repeated words and the words repeated in the same place create a structure, kind like a clothesline, and the words each "or perhaps"that follow are like pieces of the clothing you hang on the line. Proust doesn’t stop. He keeps going. He adds a lot, but he also rewrites and cuts a lot.

As I recall, the narrator imagines eleven "or perhaps"s in one sentence about the bell boy operating the lift in a hotel at Balbec.

But most of the time, Proust does not repeat nouns and verbs. He’ll use a noun one time in the entire novel. That’s it.

Characters will appear only oncw for just one or two pages.

How Best to Read In Search of Lost Time?

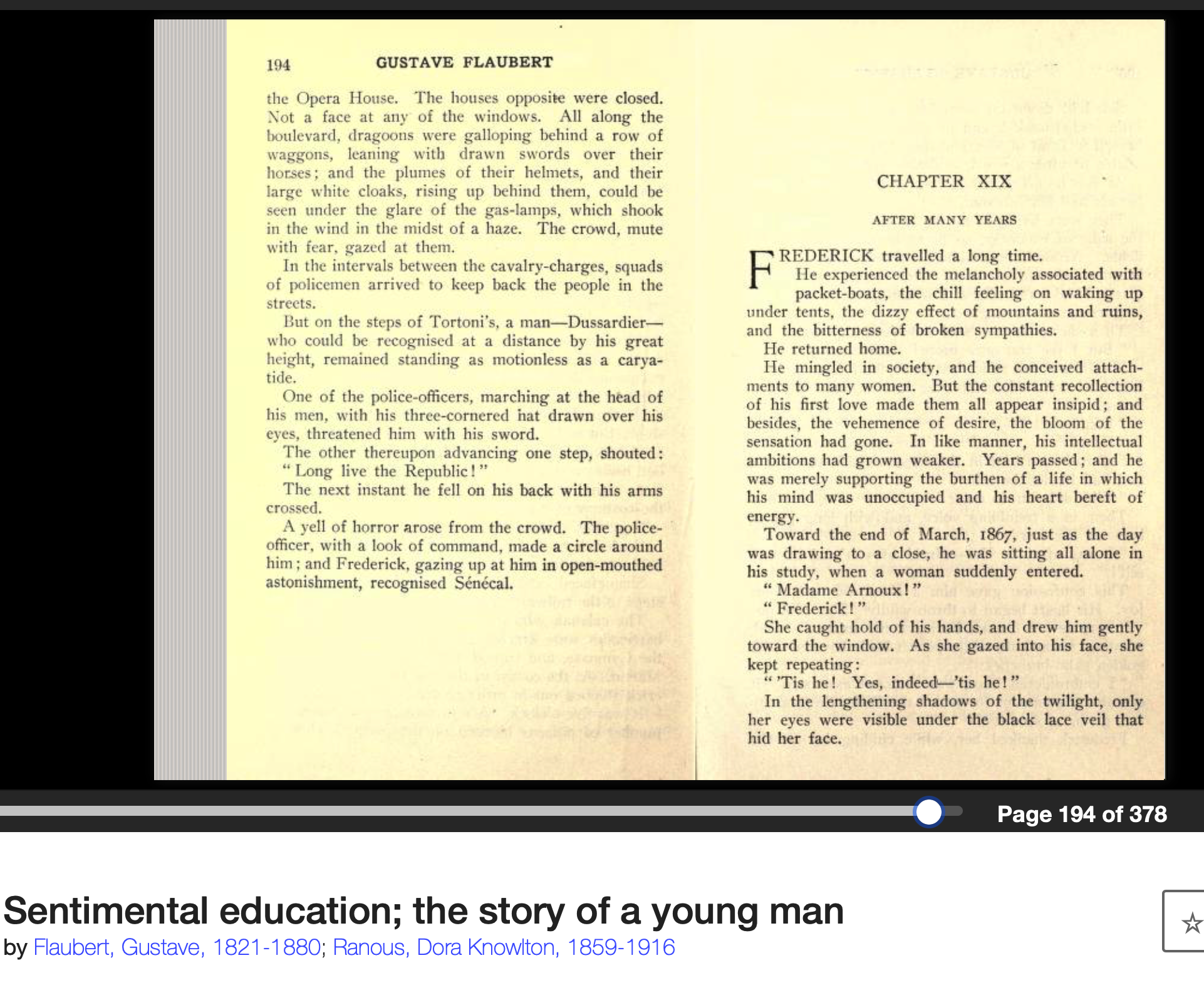

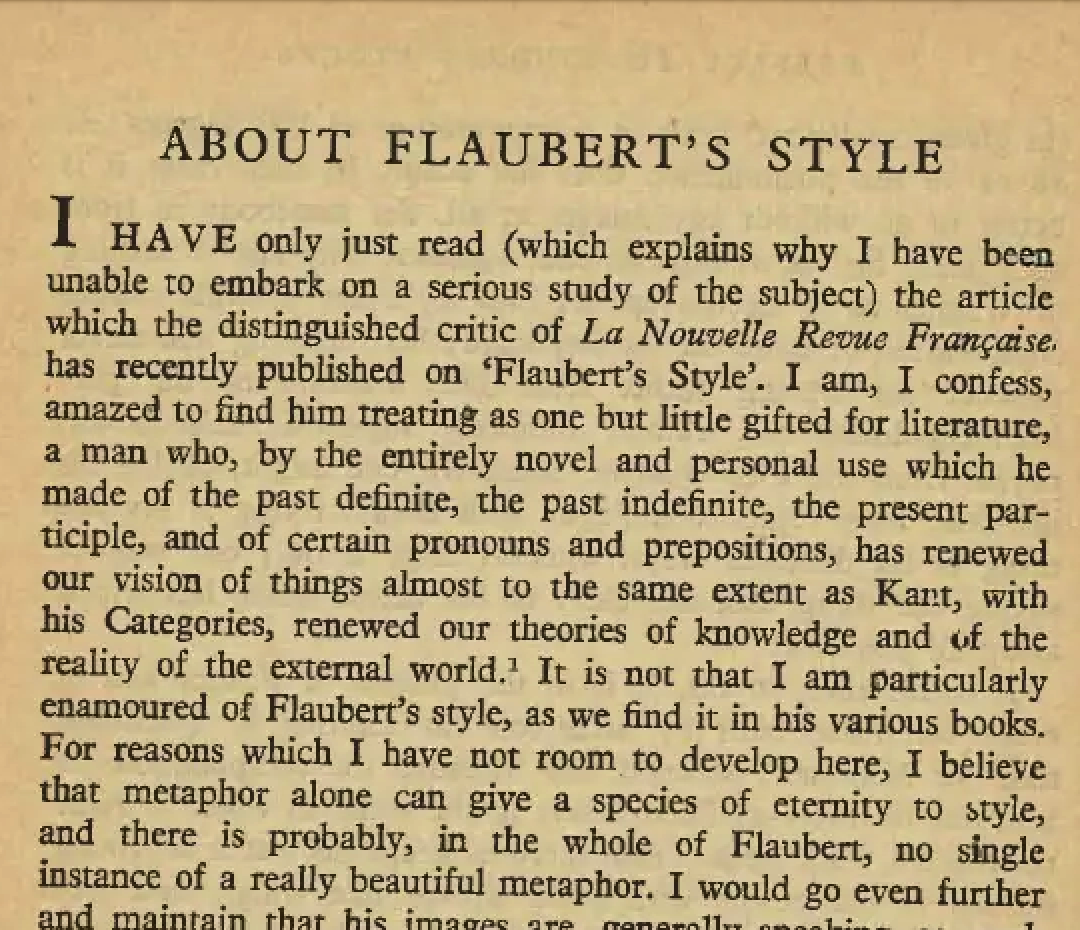

You can read the writer's literary criticism. For example, you can see very clearly what Proust cares about as a writer--grammar (especially tense) and metaphor--by reading the first few sentences of his essay "About Flaubert's Style."

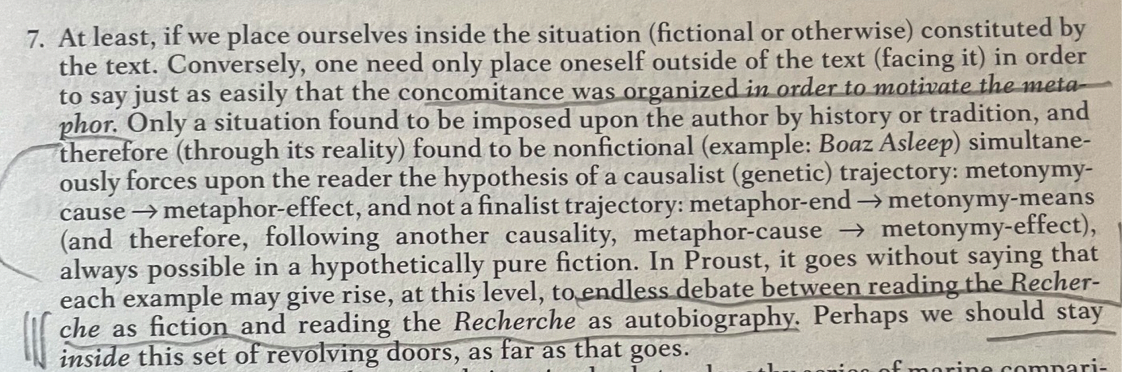

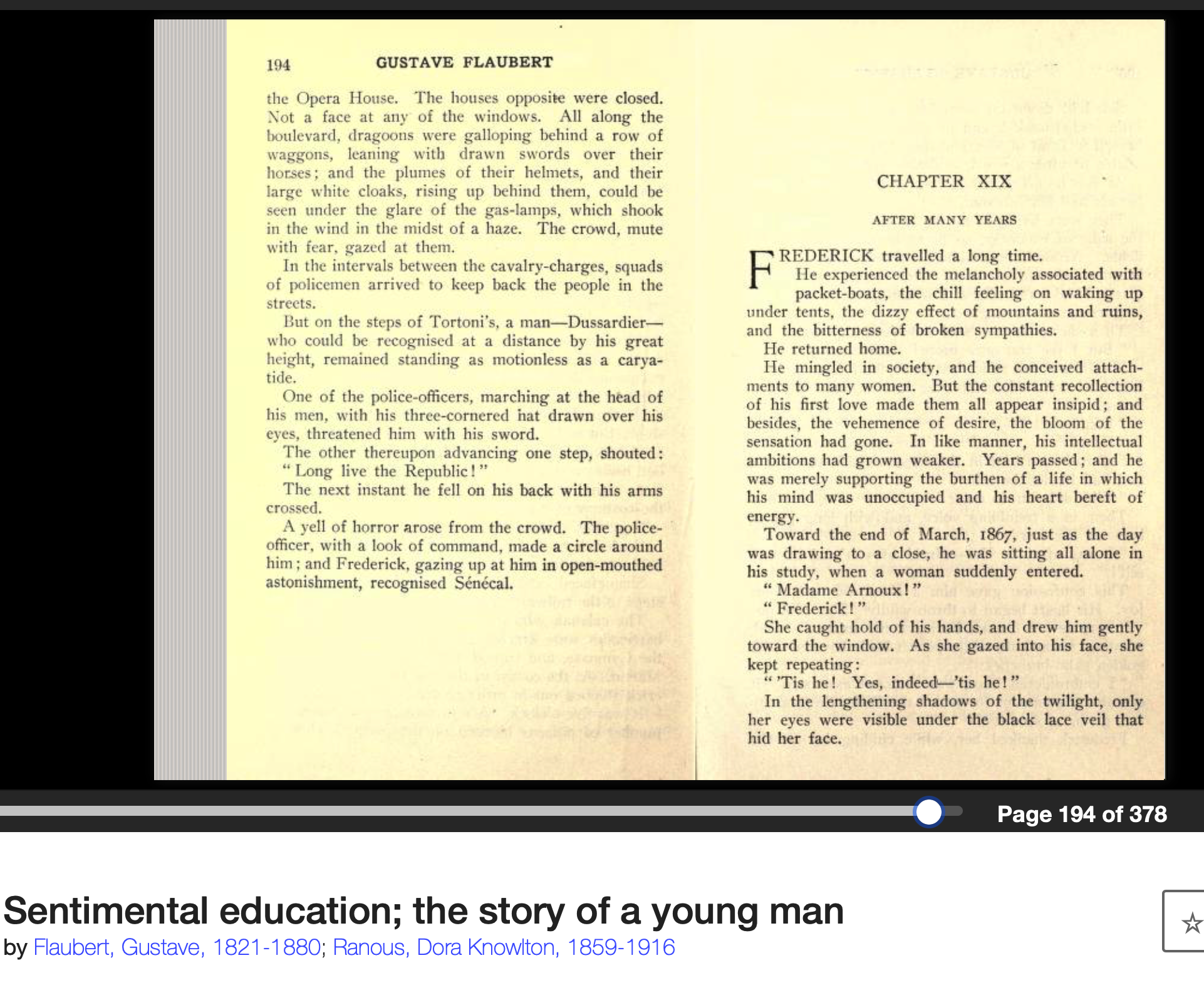

The example of Proust on Flaubert's silence, p. 234. One misremembered moment in A Sentimental Education sheds light on a huge achievement by Flaubert. (Proust forgets the chapter break and chapter title, and so accidentally improves on Flaubert by imagining more continuous narrative rather than the discontinuous narrative there in fact is, lol.) Proust is a great writer because he reads so closely and because he misreads so creatively.

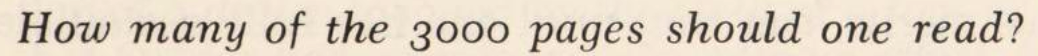

Go to an introduction to the book. Usually, you'll get a biography and some commentary on the book, like in Ian Patterson's introduction to Proust's Finding Time Again. Or you could skip the introduction and go to the first sentence of the book. Or . . . you could begin not with the book but with the writer's own thoughts about biography. Or by reading the writer's comments on what they read. So you can appreciate how the writer reads. Or . . . try reading the writer imitating other writers. Or read a great book someone wrote about reading the book you are going to read. Then go back to the book. Or you could keep going and never get back to the book. Or perhaps never finish it if your do go back.

Biographical Criticism

You Could Read the Writer Commenting on Biography (Don't cancel. It's dumb. Ad hominem denunication is not criticism)

"Sainte-Beuve championed a form of biographical criticism that saw texts as morally and intellectually inseparable from their writers. Here is Sainte-Beuve, as quoted by Proust:

So long as one has not asked an author a certain number of questions and received answers to them, though they were only whispered in confidence, one cannot be sure of having a complete grasp of him, even though these questions might seem at the furthest remove from the nature of his writings. What were his religious views? How did he react to the sight of nature? How did he conduct himself in regard to women, in regard to money? Was he rich, was he poor?[1]

Such queries led Sainte-Beuve to rank Bernard, Vinet, Molé, Verdelin, Meilhan, and Azyr among the great writers of his time, to dismiss Baudelaire and Balzac as vulgar and Hugo as overly political. History has not been on Sainte-Beuve’s side, and neither was Proust. À la recherche, the novel that grew out of this early piece of literary criticism, persuasively refutes Sainte-Beuve’s method by bringing into contrast the sometimes sordid lives of its characters and the emotional nuance of their experiences of the world. At the time Proust wrote Contre Sainte-Beuve, however, this refutation was still taking shape."

--Michael Shapiro, Contre Saint-Beuve

You Could Read How the Author Writes by [Mis]Reading Another Writer Who Wrote on How He Read [What] that Author [Didn't Write].

Nina Companeez tackles À la recherche du temps perdu

Or You Could Read a Great Book Someone Else Wrote about Reading the Even Greater Book You Are Going to Read.

Or You Could Read It for Wisdom:

"One should never bear grudges against people, never judge them by the memory of one unkind act, for we can never know all the good resolves and effective actions of which their souls may have been capable at another time. And so, even from the simple point of view of foresight, we make mistakes. For no doubt the bad pattern we observed on that one occasion will recur. But the soul is richer than that, has many other patterns which will also recur in the same man, yet we refuse to take pleasure in them because of one piece of bad behavior in the past."

The Prisoner, trans. Carol Cook, p. 311

Or you could wait to discover an introduction in the novel.

Here is what Proust writes about fictional introductions:

Novelists sometimes pretend in an introduction that while travelling

in a foreign country they have met somebody who has told them the

story of a person's life. They then withdraw in favour of this casual

acquaintance, and the story that he tells them is nothing more or less than

their novel. Thus the life of Fabrice del Dongo was related to Stendhal by

a Canon of Padua. [See also Abbé Prévost's Manon Lescaut; Denis Diderot's

The Nun; The Arabian Nights / 1,001 Nights] How gladly would we, when

we are in love, that is to say when another person's existence seems to us mysterious, find some such well-informed narrator! And undoubtedly he exists. Do we not

ourselves frequently relate, without any trace of passion, the story of

some woman or other, to one of our friends, or to a stranger, who has

known nothing of her love-affairs and listens to us with keen interest?

The person that I was when I spoke to Bloch of the Duchesse de Guermantes,

of Mme. Swann, that person still existed, who could have

spoken to me of Albertine, that person exists always… but we never

come across him. It seemed to me that, if I had been able to find women

who had known her, I should have learned everything of which I was

unaware. And yet to strangers it must have seemed that nobody could

have known so much of her life as myself. Did I even know her dearest

friend, Andrée? Thus it is that we suppose that the friend of a Minister

must know the truth about some political affair or cannot be implicated

in a scandal. Having tried and failed, the friend has found that whenever

he discussed politics with the Minister the latter confined himself to

generalisations and told him nothing more than what had already appeared

in the newspapers, or that if he was in any trouble, his repeated attempts

to secure the Minister's help have ended invariably in an: "It is not in my

power" against which the friend is himself powerless. I said to myself: "If

I could have known such and such witnesses!" from whom, if I had

known them, I should probably have been unable to extract anything

more than from Andrée, herself the custodian of a secret which she refused

to surrender. Differing in this respect also from Swann who, when

he was no longer jealous, ceased to feel any curiosity as to what Odette

might have done with Forcheville, even after my jealousy had subsided,

the thought of making the acquaintance of Albertine's laundress, of the

people in her neighbourhood, of reconstructing her life in it, her

intrigues, this alone had any charm for me.

--Proust, The Fugitive trans. C K Scott Moncrieff

Or perhaps you could read the way an author mimics another's style so well you're not sure who wrote it. Flaubert imitated many famous French writers in this book:

Marcel Proust, The Lemoine Affair. Here is the linked pdf; read for free online here with "look inside." (TRANSLATOR CHARLOTTE MANDELL)

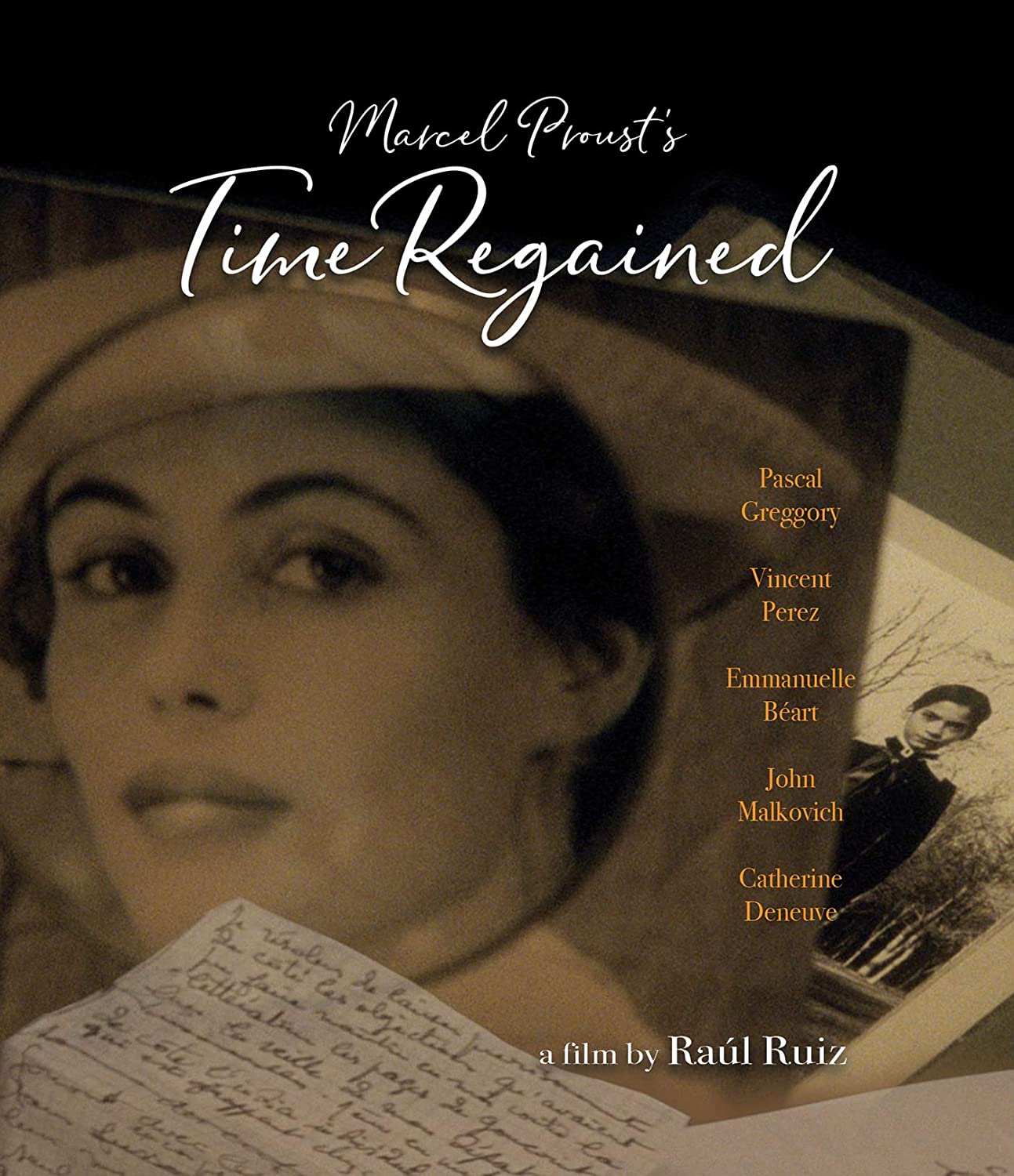

Or perhaps you could watch the trailer to a film adaptation.

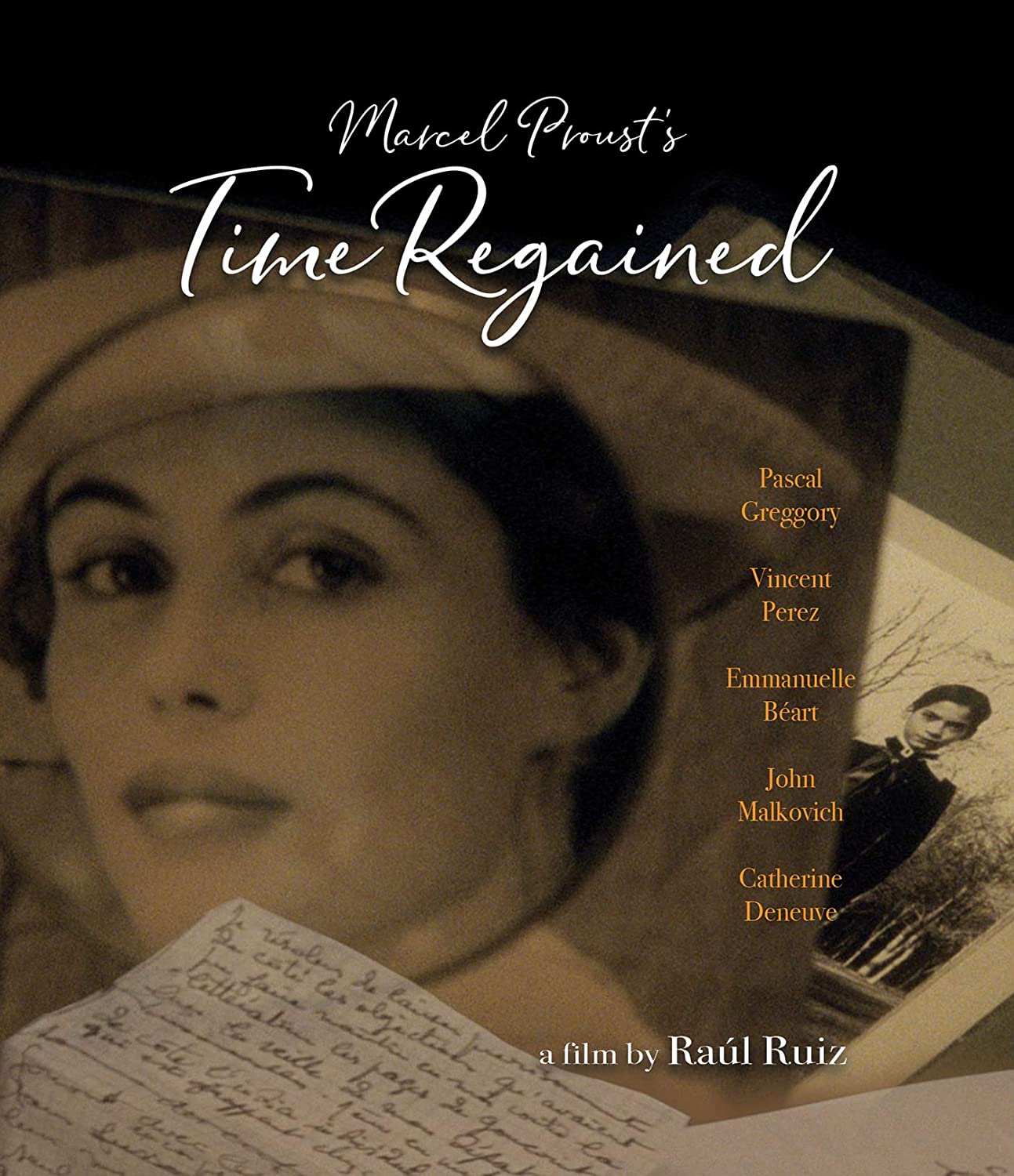

Time Regained (dir. Raul Ruiz, 1999)

Or you could watch a clip from a French TV (2011) adaptation.

https://www.editionsmontparnasse.fr/p1937/A-LA-RECHERCHE-DU-TEMPS-PERDU-2-DVD-DVD

Time Regained (dir. Raul Ruiz, 1999) / Trailer (2018)

Trailer (2018)

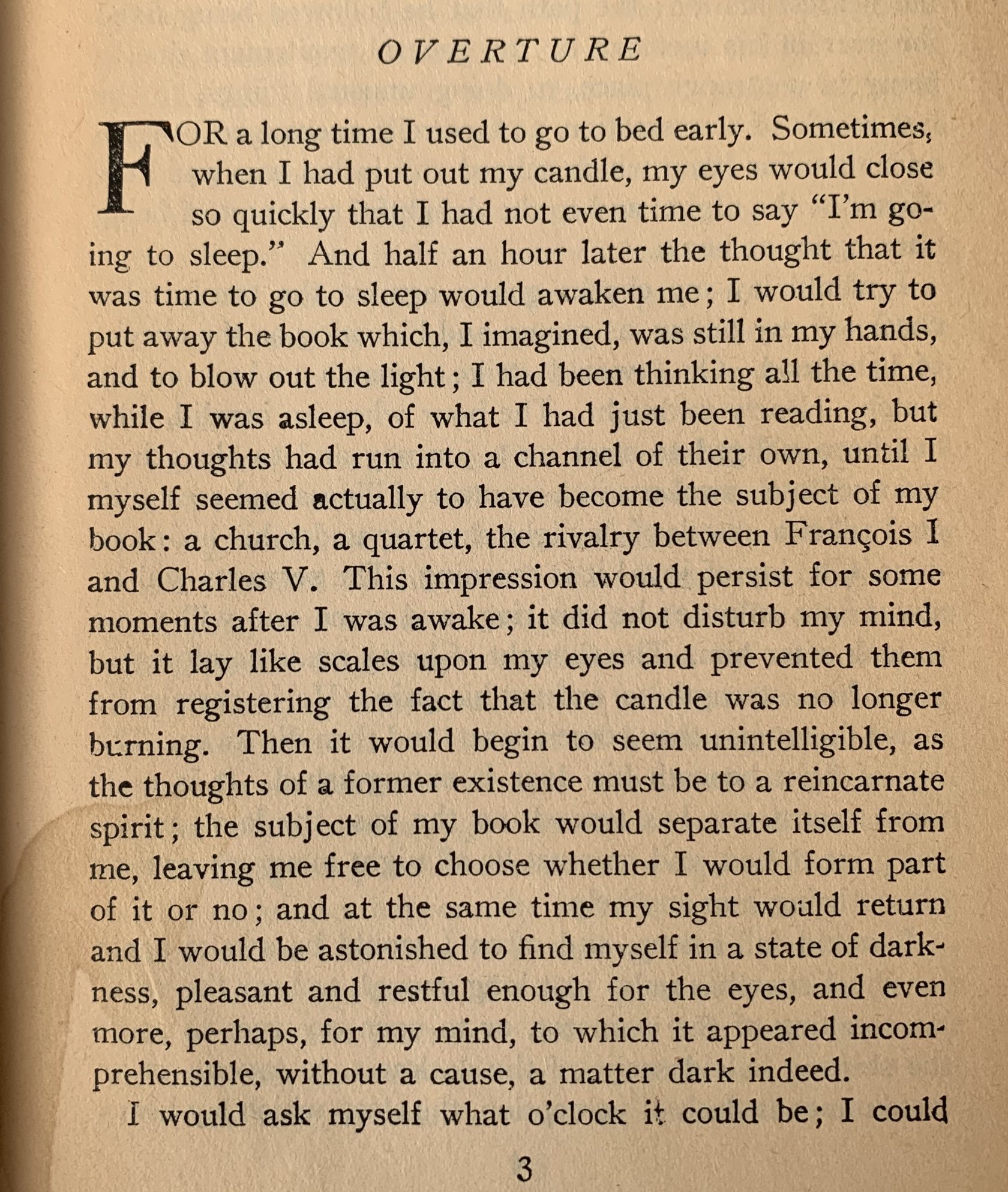

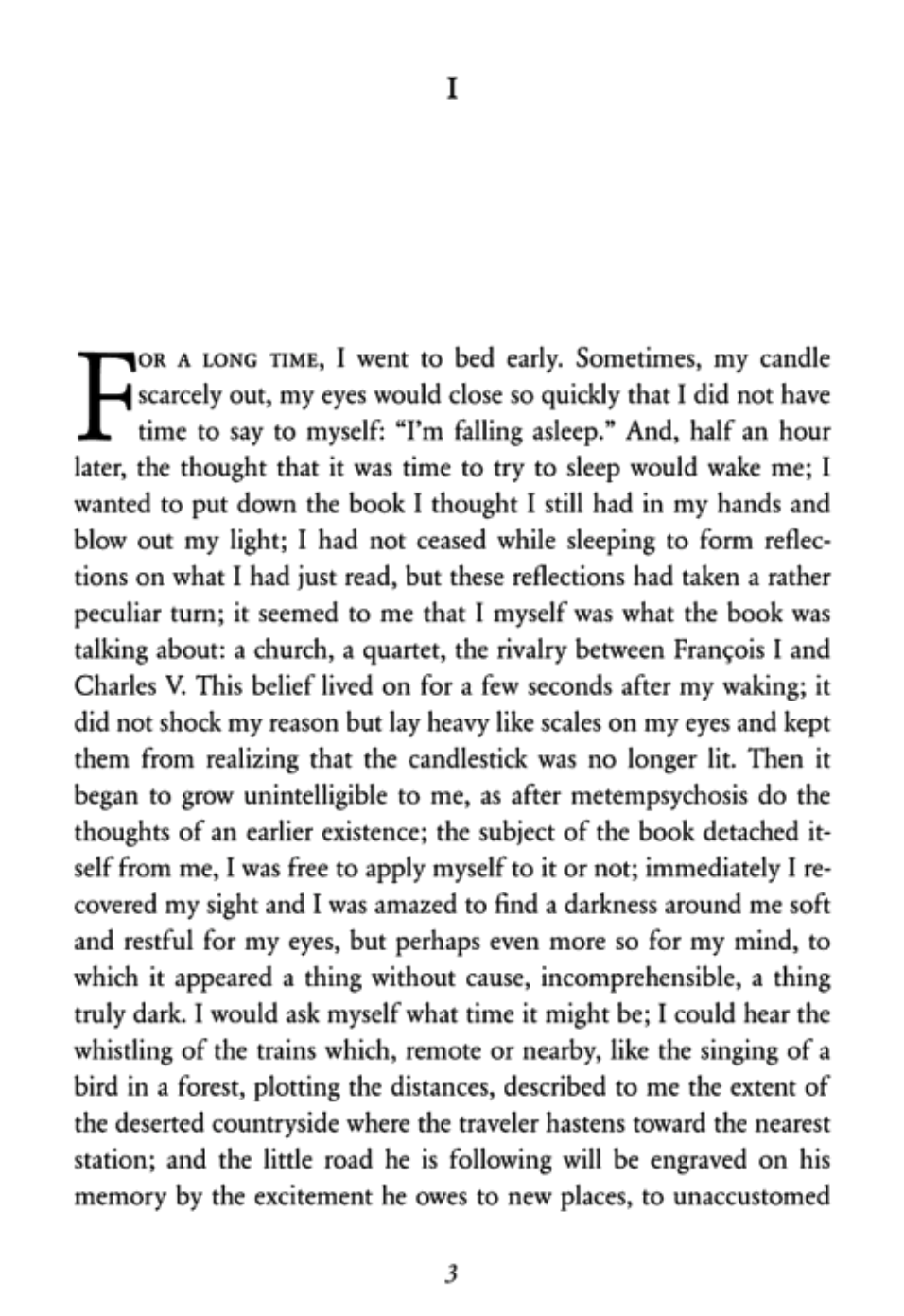

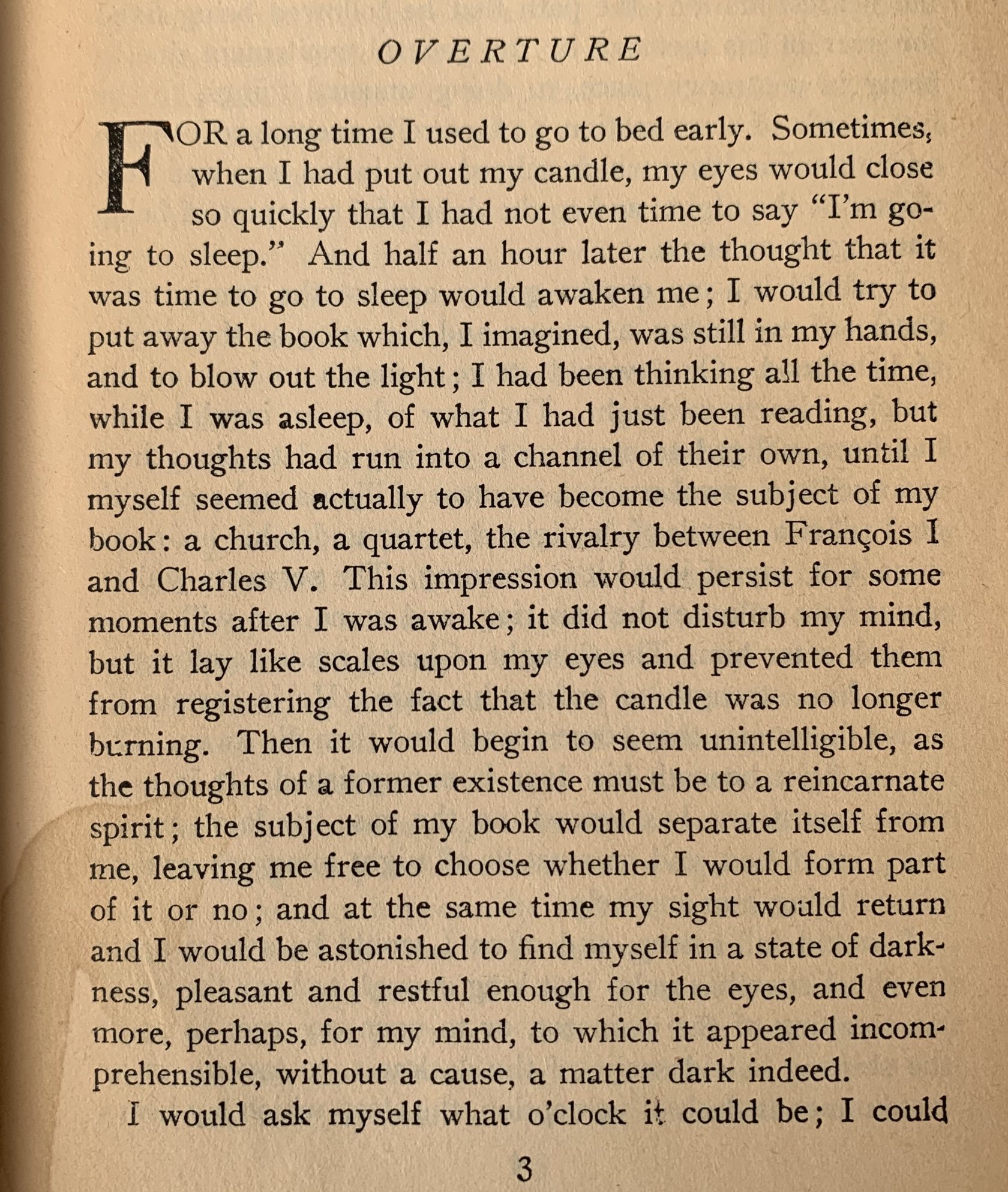

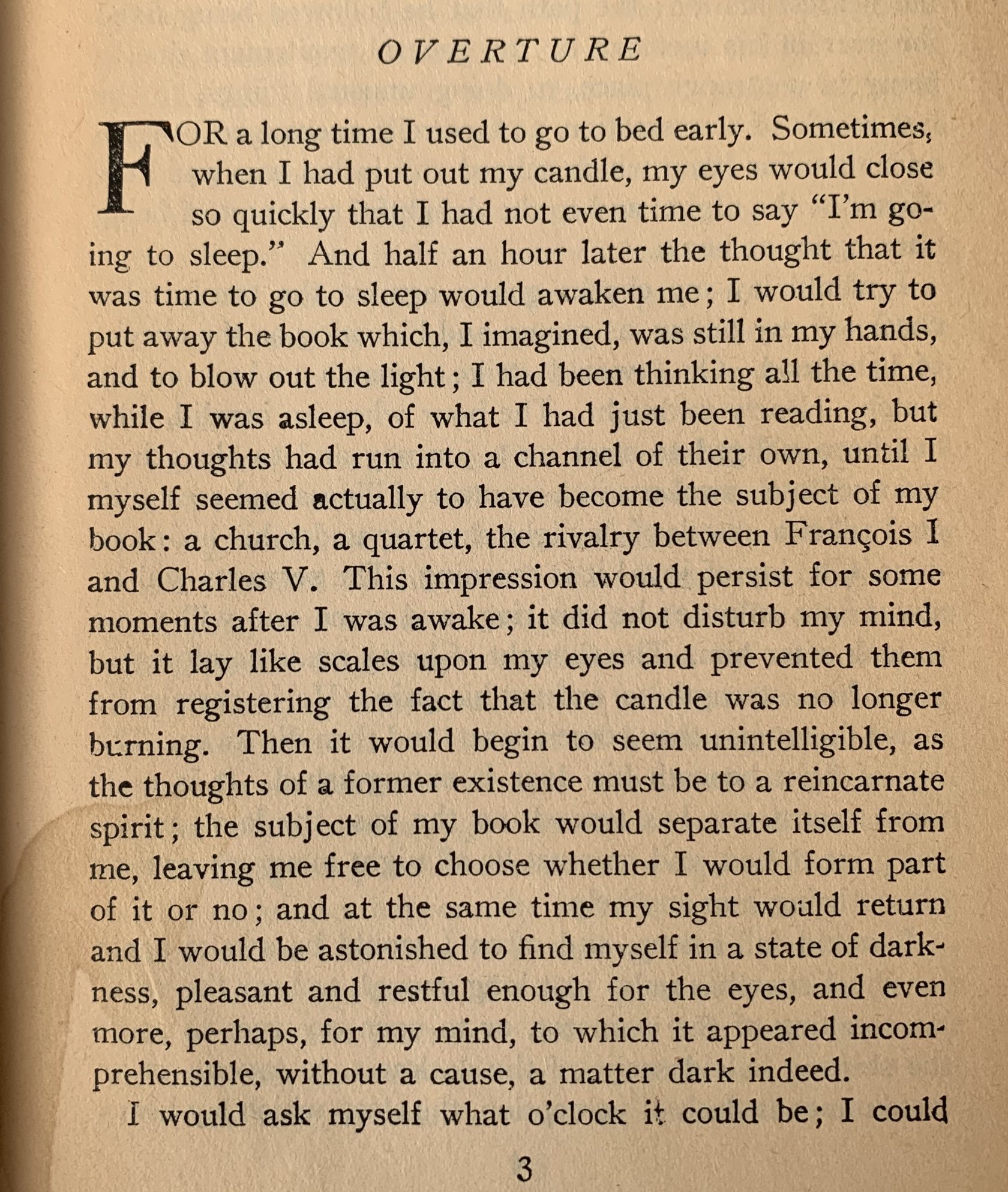

“Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure."

“For a long time I used to go to bed early.” Scott Moncrieff-Terence Kilmartin

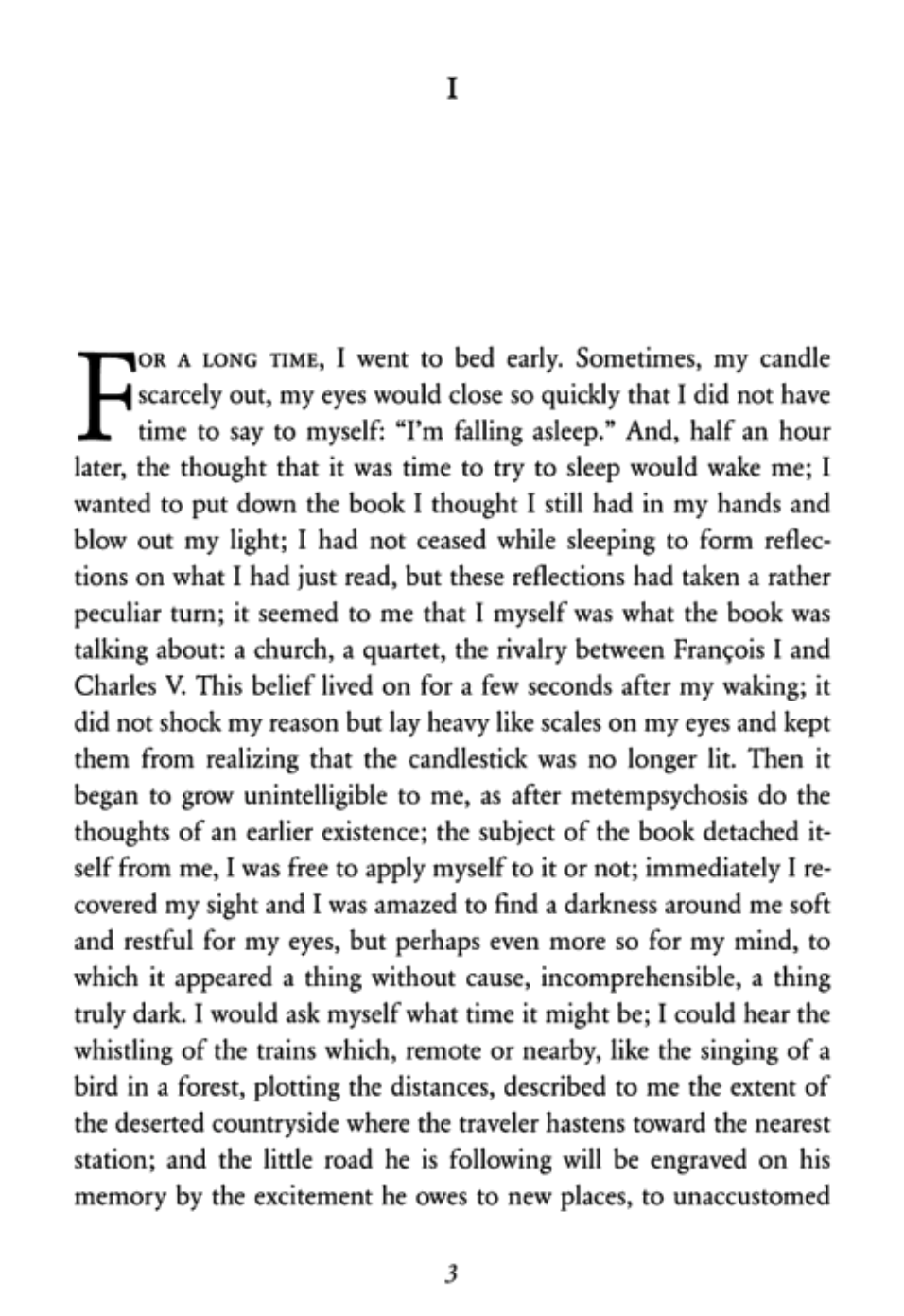

"For a long time, I went to bed early." Lydia Davis

"For a long time I would go to bed early."

“Time was when I always went to bed early." James Grieve; Richard Howard (translating Roland Barthes' "Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.")

“Time and again, I have gone to bed early.” Richard Howard

The recurrence of the word "time"

The first sentence of Swann's Way

The hilarious scene of Baron Charlus expressing his dissatisifaction with the gigolo who is whipping him in Time Found Again

Albertine's refusal of a kiss from the narrator at the end of In the Shadow of Young Girls

Albertine's invitation to the narrator to kiss her in The Guermantes Way.

Who is Gerard Genette?

What does "lost time" mean in the title In Search of Lost Time?

"Proust's work is a complete-incomplete work."

--Maurice Blanchot, "The Experience of Proust," in The Book to Come, p. 24.

Thus, not only is the Recherche, as Blanchot says, a "completed-incompleted" work, but its very reading is completed in completion, forever in suspense, forever "to be taken up again," since the object of that reading is constantly thrown into a dizzy rotation."

--Gérard Genette, "Proust Palimpsest," Figures of Literary Discourse, p. 222

"The Recherche, more than all other works, must not be considered closed. . . .

If the Recherche was complete once, it is not so anymore, and the way in which it

admitted the extraordinary later expansion perhaps proves that

that temporary completion was, like all completion, only a retro-

spective illusion. We must restore this work to its sense of un-

fulfillment, to the shiver of the indefinite, to the breath of the

imperfect. The Recherche is not a closed object: it is not an object.

Here again, no doubt Proust's (involuntary) practice goes be-

yond his theory and his plan — let us say at least that it corre-

sponds better to our desire."

-Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse An Essay on Method Translated by Jane E. Lewin Foreword by Jonathan Culler (Cornell University Press), 21; 268. facsimile / html

In fact each moment of the Recherche appears in a sense twice over: first in the Recherche as the birth of a vocation and second in the Recherche as the exercise of this vocation: but these two are not given to the reader together, and it is the lot of the reader informed in extremis that the book he has just read remains to be written and that this book is more or less (but only more or less) the one he has just read --to go back to those distant pages, to the childhood at Combray, the evening at the Guermantes, the death of Albertine, which he had read as safely deposited, gloriously embalmed in a finished work, and which he must now read again, identical in fact but a little different, as if in abeyance, still unburied, anxiously stretching forward an as yet unfinished work, and conversely, forever. Thus, not only is the Recherche du temps perdu, as Blanchot says, a 'completed-uncompleted' work, but its very reading is competed in incompletion, forever in suspense, forever 'to be taken up again' since the object of that reading is constantly thrown into a dizzying rotation."

Thus, not only is the Recherche, as Blanchot says, a "completed-incompleted" work, but its very reading is completed in completion, forever in suspense, forever "to be taken up again," since the object of that reading is constantly thrown into a dizzy rotation."

--Gérard Genette, "Proust Palimpsest," Figures of Literary Discourse, pp. 203-28; to p. 222

"But for me it was enough if, in my own bed, my sleep was so heavy as completely to relax my consciousness; for then I lost all sense of the place in which I had gone to sleep, and when I awoke at midnight, not knowing where I was, I could not be sure at first who I was; I had only the most rudimentary sense of existence, such as may lurk and flicker in the depths of an animal’s consciousness; I was more destitute of human qualities than the cave-dweller . . . . "

--Marcel Proust, Swann's Way

Third Question:

Readers may already have observed that neither the title nor the subtitle of this book mentions what I have just designated as its specific subject. The reason is neither coyness nor deliberate inflation of the subject. The fact is that quite often, and in a way that may exasperate some readers, Proustian narrative will seem neglected in favor of more general considerations; or, as they say nowadays, criticism will seem pushed aside by "literary theory," and more precisely by the theory of narrative or narratology. I could justify and clarify this ambiguous situation in two very different ways. I could either—as others have done elsewhere—frankly put the specific subject at the service of the general aim, and critical analysis at the service of theory: in that case the Recherche would be only a pretext, a reservoir of examples, and a flow of illustration for a narrative poetics in which the specific features of the Recherche would vanish into the transcendence of "laws of the genre." Or, on the other hand, I could subordinate poetics to criticism and turn the concepts, classifications, and procedures proposed here into so many ad hoc instruments exclusively intended to allow a more precise description of Proustian narrative in its particularity, the "theoretical" detour being imposed each time by the requirements of methodological clarification.

I confess my reluctance—or my inability—to choose between these two apparently incompatible systems of defense. It seems to me impossible to treat the Recherche du temps perdu as a mere example of what is supposedly narrative in general, or novelistic narrative, Or narrative in autobiographical form, or narrative of God knows what other class, species, or variety. The specificity of Proustian narrative taken as a whole is irreducible, and any extrapolation would be a mistake in method; the Recherche illustrates only itself. But, on the other hand, that specificity is not undecomposable, and each of its analyzabie features lends itself to some connection, comparison, or putting into perspective. Like every work, like every organism, the Recherche is made up of elements that are universal, or at least transindividual, which it assembles into a specific synthesis, into a particular totality. To analyze it is to go not from the general to the particular, but indeed from the particular to the general: from that incompa- rable being that is the Recherche to those extremely ordinary elements, figures, and techniques of general use and common cur- rency that I call anachronies, the iterative, localizations, paralipses, and so on. What I propose here is essentially a method of analysis; I must therefore recognize that by seeking

the specific I find the universal, and that by wishing to put theory at the service of criticism I put criticism, against my will, at the service of theory. This is the paradox of every poetics, and doubtless of every other activity of knowledge as well: always torn between those two unavoidable commonplaces—that there are no objects except particular ones and no science except of the general—but always finding comfort and something like attrac- tion in this other, slightly less widespread truth, that the general is at the heart of the particular, and therefore (contrary to the common preconception) the knowable is at the heart of the mysterious.

--Gérard Genette, "Preface," Figures of Literary Discourse,

Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse An Essay on Method Translated by Jane E. Lewin Foreword by Jonathan Culler (CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS) facsimile / html

Genette, Narrative Discourse on the seven beginnings of Swann's Way

https://15orient.com/files/genette-on-narrative-discourse.pdf

All that is left is for the narrator to treat that element of the Sabbath ritual like the others, that is, in the iterative mode, in order to "iteratize," as it were, the deviant event in its turn, in accord with this irresistible process: singular event—repetitive narrating—iterative narrative (of that narrating)

p. 127

An example of the second is the episode of the steeples of Martinville, plainly presented as a deviation from habit: ordinarily, once he was back from his outing, Marcel for-got the impressions he had experienced and did not try to cipher their significance; "Once, however," he goes further and writes down immediately the descriptive piece that is

first work and the sign of his vocation.

pp. 139-40

And if in some cases—where we are dealing, for instance, with the inaccurate language of our own vanity—the rectification of an oblique interior discourse which deviates gradually more and more widely from the first and central impression, so that it is brought back into line and made to merge with the authentic words which the impression ought to have generated, is a laborious undertaking which our idleness would prefer to shirk, there are other circumstances—for example, where love is involved—in which this same process is actually painful. Here all our feigned indifferences, all our indignation at the lies of whomever it is we love (lies which are so natural and so like those that we perpetrate ourselves), in a word ail that we have not ceased, whenever we are unhappy or betrayed, not only to say to the loved one but, while we are waiting for a meeting with her, to repeat endlessly to ourselves, sometimes aloud in the silence of our room, which we disturb with remarks like: "No, really, this sort of behavior is intolerable," and: "I have consented to see you once more, for the last time, and I don't deny that it hurts me," all this can only be brought back into conformity with the felt truth from which it has so widely diverged by the abolition of all that we have set most store by, all that in our solitude, in our feverish projects of letters and schemes, has been the substance of our passionate dialogue with ourselves.

--Proust quoted By Genette, pp. 178-89

Unité ultérieure, non factice, sinon elle fût tombée en poussière comme tant de systématisations d'écrivains médiocres qui à grand renfort de titres et de sous-titres se donnent l'apparence; d'avoir poursuivi un seul et transcendant dessein.

-The Prisoner

Ebooks for the Modern Library and Penguin editions may be found here. They may be available for less at other online vendors.

Marcel Proust | A la recherche du temps perdu | Texte intégral

The Five Longest Proust Sentences

Cleanth Brooks, "The Heresy of Paraphrase," in The Well Wrought Urn (1947)

How do we understand another mind? (Time Regained) What is Proustian? (involuntary memory; madeleine dipped it tea; Chris Marker, Rememory) What is Proustian about Proust?

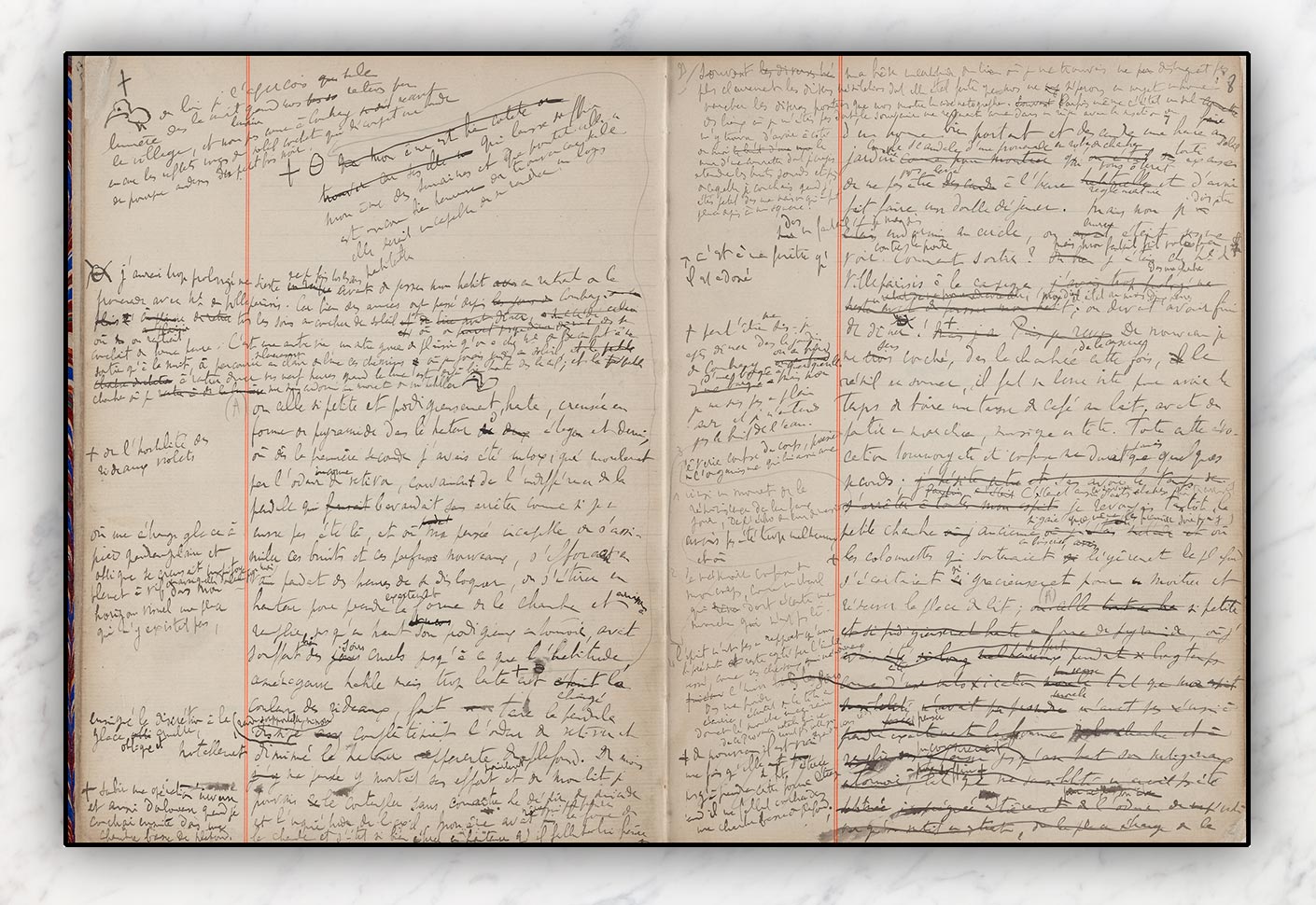

Galley Sheets for Swann's Way

"Proust is too long."

--Pierre Bayard, Le hors-sujet : Proust et la digression (1996)

Georges Poulet, Proustian Space (1977)

Gerald Prince, "On Narratology"

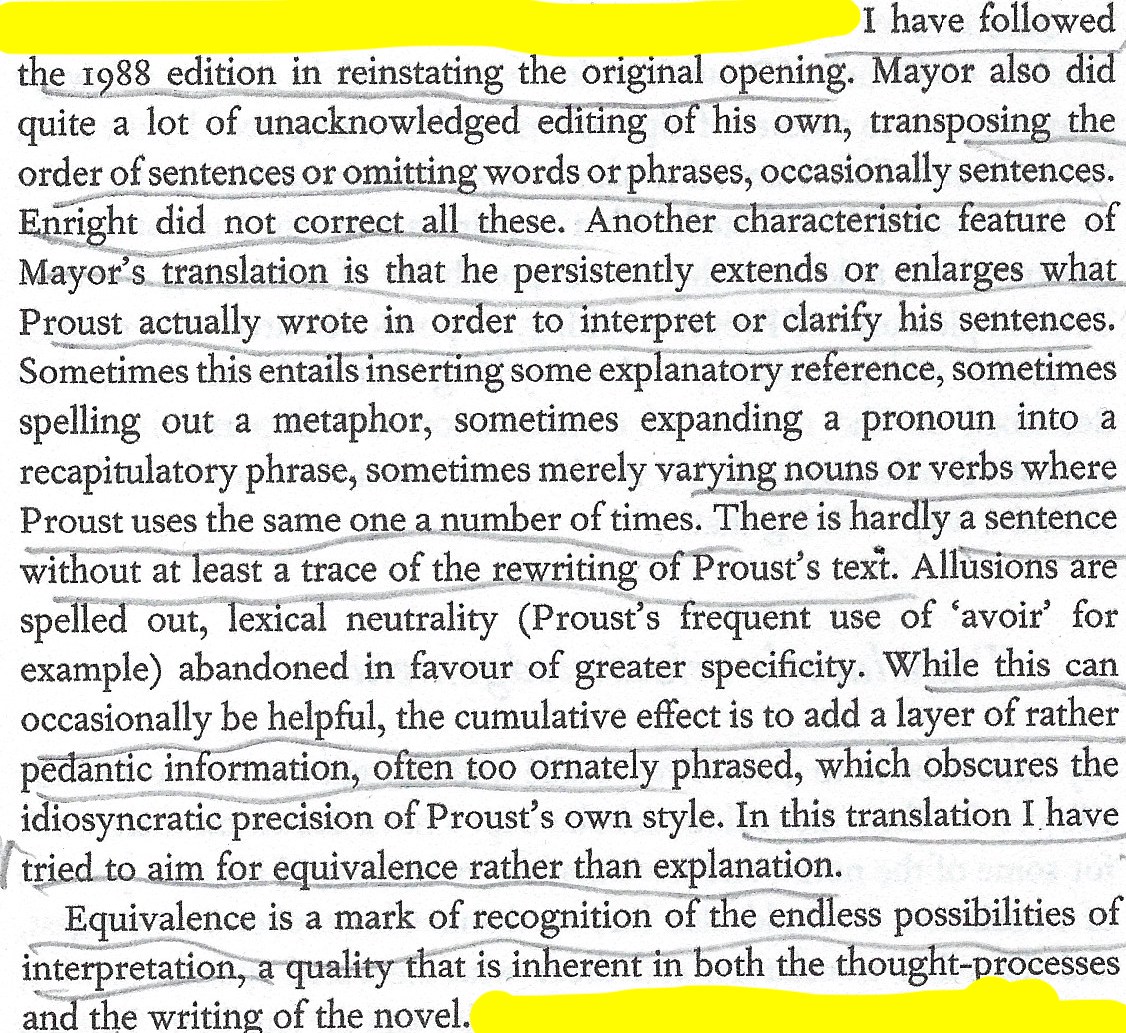

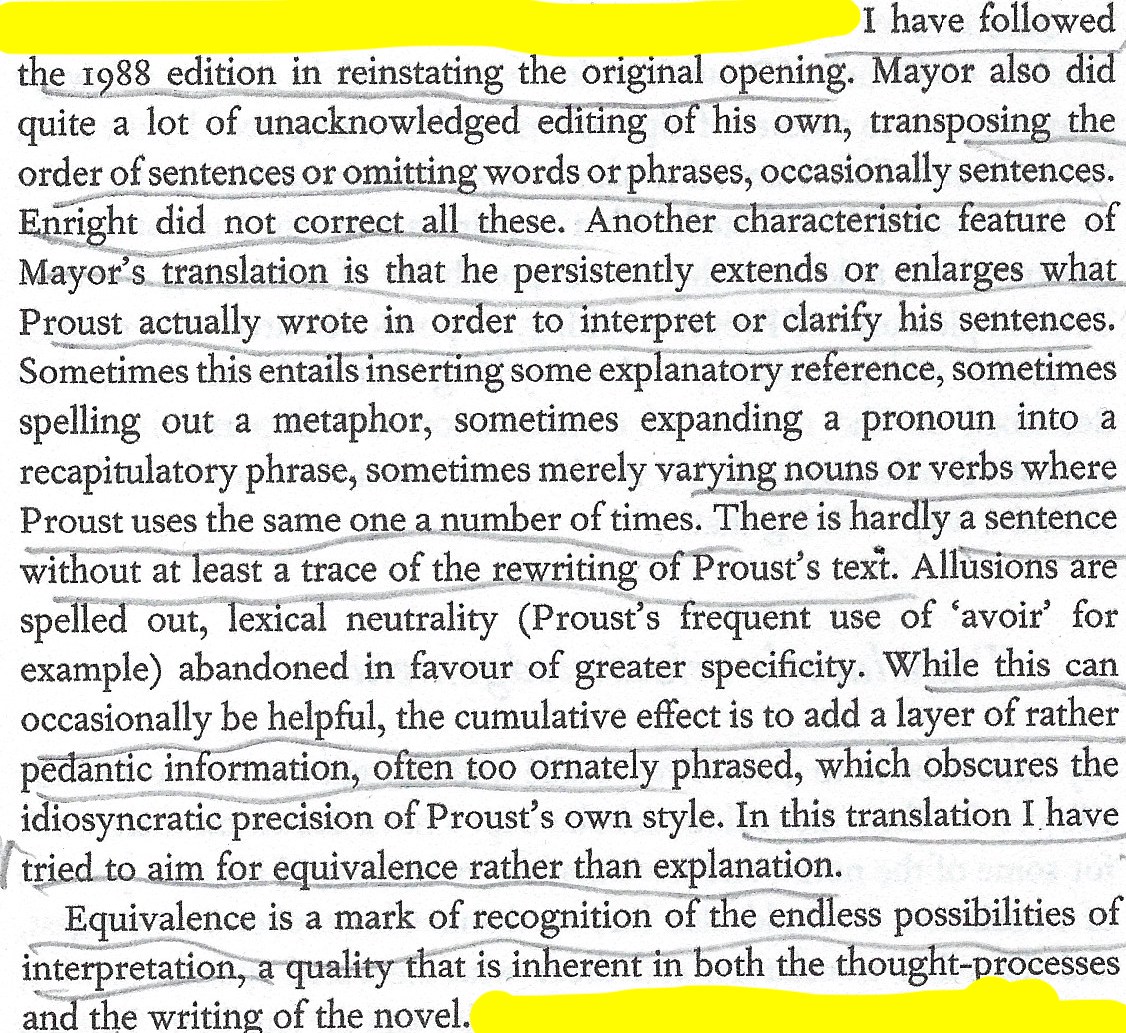

"In the end, one is prompted to ask who this translation is for. It's a question addressed neither by Prendergast in his general introduction nor by the individual translators in the brief prefatory essays they have provided to each volume (excellent though some of them are, notably those to The Guermantes Way and The Prisoner, as thumbnail critical sketches of the novels). Certainly, the Penguin Proust, as compared with Moncrieff/Kilmartin/ Enright, establishes a new benchmark of fidelity; but, since it does so at the price of much oddly un-English prose, what sort of reader will stay the whole course? Perhaps one adept in French but not quite up to the task of scaling Proust unaided, who might keep the Penguin open alongside his French text to help him over craggy sections of the original. Yet readers willing to toil through the 3,300 pages of the novel in this sort of do-it-yourself parallel text will surely be few and far between. For those without French considering setting out on the Proustian journey, the Moncrieff/ Kilmartin/Enright translation, remains, in my view, the best available reading text. "

--Paul Davis, "Reviving the Dread Deity," Swann's Way: A Search for Lost Time. Translation James Grieve 1982. Proust and Genette can both be melancholic and humorous, sometimes at the same time. How can we understand other minds? Problems include not listening or paying attention; not looking but radiographing other people (Finding Time Again, pp. 24-25)

"One should never bear grudges against people, never judge them by the memory of one unkind act, for we can never know all the good resolves and effective actions of which their souls may have been capable at another time. And so, even from the simple point of view of foresight, we make mistakes. For no doubt the bad pattern we observed on that one occasion will recur. But the soul is richer than that, has many other patterns which will also recur in the same man, yet we refuse to take pleasure in them because of one piece of bad behavior in the past."The Prisoner, p. 311 We will return to this passage later in the semester and reread it in relation to what follows a few sentences later.

Is Proust's Recherche, a novel? Or a philosophical essay? Proust himself could not decide which.

A favorite talking point of establishment, so-called progressives who support de-platforming and social media censorship by Silicon Valley tech giants is "free speech doesn't mean speech free from consequences." That is a typically vague, but also threatening neoliberal content free statement. What consequences follow from exercising your First Amendment right to free speech other than more speech? Doxxing? Getting fired from your job? If you are against free speech, that is your right. But the consequence is that I will think you are really dumb. And ignorant. And morally under-developed. And figure that you are probably white. Ditto if you are against due process. The First Amendment protects minorities and those with minority opinions from being de-platformed and censored. "Hate speech," otherwise known as "speech I don't like," is constitutionally protected speech. Guess what happens to Palestinian student activists if they organize a boycott of Israel. The Fifth Amendment guarantees due process, meaning someone is presumed innocent until proven guilty. Guess how many black men have been falsely accused and convicted of raping a white woman only to be exonerated decades later because DNA evidence proved their innocence. Have you ever seen To Kill a Mockingbird? Guess how many people convicted of murder and then executed were posthumously exonerated. Guess how many black people have been lynched. Google it. Educate yourself. Know your civil liberties. Don't be dumb, be a smartie. Universal Rights protect racial and sexual minorities. "Representation," perhaps the most cynical notion of politics ever to emerge from the elites in the history of the United States, does not. The National Security State wants your identitification papers. Authoritarianism, censorship, Big Tech demonitization and deplatforming of social media, policing who can say what where, the pre-school politics of twitter are antithetical to the thought and imaginative freedom which creating literature involves.

"Proust's work is a complete-incomplete work."--Maurice Blanchot, "The Experience of Proust " in "The Experience of Proust," in The Book to Come, pp. 11-24; to p. 24.

If you are here at UF to get an education, you will probably do well in this course. If you want to learn, I can help you learn. If you took this course because it fills a slot in your schedule, you probably will not do well. You may even fail. If you have "senioritis," you might want to take another course. Sadly, I have occasionally had to fail graduating seniors who didn't attend the course or do the work. It's not over til it's over.

Roland Barthes and Gille Deleuze roundtable on Proust in "Two Regimes of Madness" Semiotext(e)

"But I was incapable of seeing a thing unless a desire to do so had been aroused in me by reading; unless it was

a thing of which I wanted a previous sketch to confront later with reality."--Proust, Finding Time Again

Full text of In Search Of Lost Time ( Complete Volumes) dipliomatic transcription in html

In Search Of Lost Time (Complete Volumes) digital facsimile

Who's Who in Proust? Ordre d’entrée en scène des personnages

Deepl Translator

Proust, ses personnages (the editions and English translations)

Proust First Day of Class / Resources / Translations

Merriam-Webster / Oxford English Dictionary (you'll need to log-in through UF.)

How To Pronounce Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust and Swann's Way: 100th Anniversary (2013)

Vera A. Klekovkina, "Proust's souvenir visuel and Ruiz's clin d'œil in Le Temps retrouvé," L'Esprit Créateur Vol. 46, No. 4, Proust en devenir (Winter 2006), pp. 151-163

David Ellison, A Reader's Guide to Proust's 'In Search of Lost Time' 2010

'How full of meaning and significance the language of music is we see from the repetition signs, as well as from the Da capo which would be intolerable in the case of works composed in the language of words. In music, however, they are very appropriate and beneficial; for to comprehend it fully, we must hear it twice.'

Arthur Schopenhauer, "On the Metaphysics of Music"

The First Confidential Report of Swann's Way

Honoré de Balzac's novella The Girl with the Golden Eyes comes up in Time Regained.

What is Balzacian about Balzac? How does he tell the story? "This is the story of . . . " What saves the novella from being merely the product of an angry, misanthropic, dyspeptic old man?

Title: The Girl with the Golden Eyes Honore de Balzac Translator: Ellen Marriage (digital auto-dramatization vs. dramatic reading by a real person)

Alfred de Musset

London Grammar - Rooting For You

Still Corners - Black Lagoon

Chris Isaak - Wicked Game

Lana Del Rey - Summertime Sadness

CHROMATICS "SHADOW"

“Many people will disagree with what I have to say now, but I shall confine myself to those who have been, shall I say, unhappy enough to love passionately for many years, unrequitedly and against hopeless odds.”

----Gérard Genette, "Proust Palimpsest," Figures of Literary Discourse, p. 164

"Proust's work is a complete-incomplete work."

--Maurice Blanchot, "The Experience of Proust," in The Book to Come, p. 24.

Thus, not only is the Recherche, as Blanchot says, a "completed-incompleted" work, but its very reading is completed in completion, forever in suspense, forever "to be taken up again," since the object of that reading is constantly thrown into a dizzy rotation."

--Gérard Genette, "Proust Palimpsest," Figures of Literary Discourse, p. 222

Complete? or Completed? Blanchot's sentence in French is below.

IPA/French / English pronunciation of French / Deepl French to English Translator / Cambridge French to English translator (don't rely on just one. Sometimes a nonsensical English word appears; that's because it's a bad translation. Try "préséance," for example. "Preset"? Or "precedence?")

“Many people will disagree with what I have to say now, but I shall confine myself to those who have been, shall I say, unhappy enough to love passionately for many years, unrequitedly and against hopeless odds.”

----Gérard Genette, "Proust Palimpsest," Figures of Literary Discourse, p. 164

Le Temps retrouvé, 1954 Pléiade edition

The word "longtemps," near the beginning of the last sentence, recalls the first word of the novel. English translations lose this repetition, a word that occurs many times across the Recherche, including the second to last sentence. Translators are forced to adopt variations of "long enough" or "time enough" since the adjective that modifies "longtemps," "assez" means "enough."

I was terrified that my own were already so high beneath me and I did not think I was strong enough to retain for long a past that went back so far and that I bore within me so painfully. If at least, time enough were alloted to me to ac-complish my work, I would not fail to mark it with the seal of Time, the idea of which imposed itself upon me with so much force to-day, and I would therein describe men, if need be, as monsters occupying a place in Time infinitely more important than the restricted one reserved for them in space, a place, on the, contrary, prolonged immeasurably since, simultaneously touching widely separated years and the distant periods they have lived through—between which so many days have ranged themselves—they stand like giants immersed in Time.

--Time Regained

Journalism; Reading the Goncourt brothers journal

"And, when snuffing out the candle before I read the passage I transcribe below. . . So I closed the Goncourts' journal." Finding Time Again, pp. 15-23

"Here are the pages that I read before fatigue closed my eyes . . . There I stopped," Time Regained, pp. 27-38

The aged but still randy Baron and Jupien at the matinée at the House of the Princesse de Guermantes.

How to Pronounce Charlus - PronounceNames.com

How to Pronounce Marcel Proust? (CORRECTLY)

Time Regained (dir. Raul Ruiz, 1999)

Trailer (2018)

-

Three involuntary memories the narrator has in Time Regained:

1. The narrator's involuntary memory of stumbling over a cobblestone (taking him to Venice, in the film)

2. The narrator's involuntary memory of the sound of a train wheel being tapped by a train engineer when the narrator hears the sound of a spoon stirring a cup of tea in the Guermantes library.

3. The narrator's involuntary memory of a stiff napkin he used in a hotel at Balbec when he uses a similar napkin to wipe his mouth after drinking the cup of tea:

"Lost Time" is not the past.

"Lost Time" (p. 185) in the title does not mean the past. It means "extratemporal," or eternity, a fleeting, joyous, something one can experience outside of time (chronological or clock time) through involuntary memory (combining a moment from the past to an analogous moment in the present) and reading books, an experience that "resurrects" and puts death out of mind is a way to find it. See the library scene in Finding Time Again (Viking / Penguin, Trans. Ian Patterson, pp. 173-88) In the Montrieff translation linked below, the passage begins with "I got out of the carriage again" and ends with "sweetness of a mystery which is but the twilight through which we have passed. " "Of a truth, the being within me which sensed this impression, sensed what it had in common in former days and now, sensed its extra-temporal character, a being which only appeared when through the medium of the identity of present and past, it found itself in the only setting in which it could exist and enjoy the essence of things, that is, outside Time."

Lost time is not only extra-temporal, outside of linear time, for Proust, but omni-temporal.

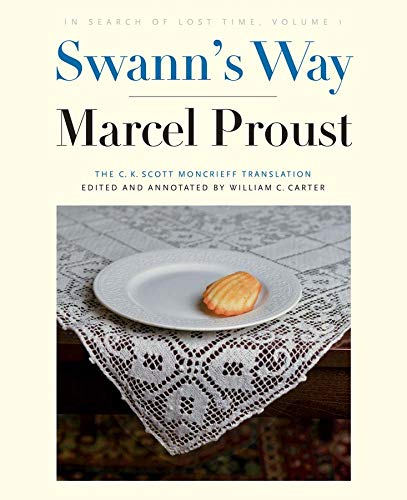

Marcel Proust, SWANN'S WAY Remembrance Of Things Past, Volume One

Translated From The French By C. K. Scott Moncrieff NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 1922

Vera A. Klekovkina, "Proust's souvenir visuel and Ruiz's clin d'œil in Le Temps retrouvé," L'Esprit Créateur Vol. 46, No. 4, Proust en devenir (Winter 2006), pp. 151-163

Key concepts of narratology: focalization / free indirect style / narrative voice: who is speaking? / narrative and discourse

MARCEL PROUST / Modernism Lab

-

- Proust, Marcel, A la recherche du temps perdu [Paris, Gallimard] 1954

Georges Poulet, L'espace proustien. pp. 47-51

Georges Poulet, Proustian Space. pp 30-32

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice Vol. 1

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice Vol. II

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Vol III

Henri Bergson, Matter And Memory

Henri Bergson, Time And Free Will

Vittore Carpaccio

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

RECOMMENDED READING:

Richard Howard, in his introduction to Time Regained (Modern Library), says the translation has completed the novel in a way Proust could not (Proust died while revising the three posthumously published novels). Yet the no one knows how the Fugitive was supposed to end. The source texts for the Modern LibraryThe Fugitive and for Time Regained the Montrieff (et al) translations differ from the more the source texts of the more recent Penguin translations. The last nine pages of the Penguin Fugitive has the first nine pages of the Modern Library Time Regained. The Penguin translator follows more recent French single volume editions of la Fugitive aka Albertine disparu and ends in the novel in the same place they do.

E-BOOKS:

In Search of Lost Time, Volume I Swann's Way (A Modern Library E-Book)

Swann's Way In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1 (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition E-Book)

LISTEN to the original, unrevised Montcrieff translation of Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time Complete Volumes read by John Rowe on Audible.com)

FREE ONLINE:

Marcel Proust, Swann's Way Trans Montcrieff, Kilmartin, Enright

In Search of Lost Time: Volume 1 Swann's Way

on archive.org: "Full text of In Search Of Lost Time ( Complete Volumes)," a dipliomatic transcription in html

In Search Of Lost Time (Complete Volumes), a digital facsimile. Both are searchable.

E-books are available for both

the Modern Library

and the more recent and more expensive

Penguin editions,

except for the Penguin translation of Finding Time Again. It is not available as an ebook, but I strongly recommend you get the print paperback of the Penguin edition of Finding Time Again trans. Ian Patterson. I ordered copies through the UF bookstore, but you may have to order a copy through an online vendor.

KEY IDEAS for the FIRST THREE WEEKS of class: complete versus incomplete; metaphor; metonymy; time as a succession of discontinuous moments, not continuous, not duration (past plus present equals eternity); lost time as not past time; essences (vision); (involuntary) memory; parapraxis (Freudian slip); published (posthumously) and unpublished; paradox; the work of art / related vocabulary people, and concepts: Western metaphysics; Plato's allegory of the cave; Henri Bergson; John Ruskin; Richard Wagner; Honoré Balzac; Gustave Flaubert . . .

--Ian Patterson , "Introduction" (and Sample Pages) Marcel Proust, Finding Time Again

You may compare some pages from Patterson's translation to the Modern Library translation (on google books) or Amazon.

Some of the Modern Library editions are available on Kindle for as low as 99 cents.

William C. Carter has translated the first four volumes of In Search of Lost Time for Yale UP and trashed both the Penguin translations and the original Montcrieff translations:

William C. Carter "Lost in Translation" Modernism/modernity Johns Hopkins University Press Volume 12, Number 4, November 2005 pp. 695-704

William C. Carter, "Lost in Translation: Proust and Scott Moncrieff"

This scholar has in turn trashed Carter's translations: "Style Over Substance," Boston Review. William Carter revisits the original C.K. Scott Moncrieff translation.

Kinky Proust: Mlle Vinteuil and her friend; the narrator ripping up Charlus' hat in Guermantes

RECOMMENDED READING:

Richard Howard, in his introduction to Time Regained (Modern Library), says the translation has completed the novel in a way Proust could not (Proust died while revising the three posthumously published novels). Yet the no one knows how the Fugitive was supposed to end. The source texts for the Modern LibraryThe Fugitive and for Time Regained the Montrieff (et al) translations differ from the more the source texts of the more recent Penguin translations. The last nine pages of the Penguin Fugitive has the first nine pages of the Modern Library Time Regained. The Penguin translator follows more recent French single volume editions of la Fugitive aka Albertine disparu and ends in the novel in the same place they do.

A Thousand and One Nights are also known as the Arabian Nights. New Arabian Nights (1882) is a collection of short stories by R. L. Stevenson. / New_Arabian_Nights

"In many of his comments on Proust, Barthes seems to warn against

an excess of seriousness. Good readings, of this author at least, he suggests,

are light, partial and tangential. Getting the book right is a matter

of seeing the mighty body of the text aslant and askew.“D’une lecture

à l’autre, on ne saute jamais les mêmes passages” (From one

reading to another, one never skips the same passages), he writes in Le

Plaisir du texte (1979). Besides, Proust’s entire undertaking is in a sense

an exercise in idling, he adds in one of the interviews collected

posthumously as Le Grain de la voix (1981), and it would not be in

keeping with the book’s delicious associative textures to read it in an

other than idly pleasure-seeking frame of mind. Repudiating the notion

that he might be thought a Proust “specialist,” he writes, again in

Le Plaisir du texte, “Proust, c’est ce qui me vient, ce n’est pas ce que

j’appelle; ce n’est pas une ‘autorité’” (Proust is that which comes to

me, not that which I call forth; he is not an “authority”). Only scholars

and specialists would want to turn the reading of Proust prematurely

towards long labour and goal-directed linearity. “Je ne suis pas

‘proustien’” (I am not a “Proustian”), he repeats elsewhere in Le Grain

de la voix."--Malcolm Bowie, "Barthes on Proust," The Yale Journal of Criticism, Volume 14, Number 2, Fall 2001, pp. 513-518; to p. 513.

You can find plot summaries or overviews on wikipedia and in these guide books. In some cases, the guide book is longer than Proust's novel.

Patrick Alexander, Marcel-Proust's-Search-for-Lost-Time A-Readers-Guide-to-Remembrance-of-Things-Past (Vintage 2009)

In Search of Lost Time, Volume VI: Time Regained Reader’s Guide

Terence Kilmarten, A Reader's Guide to Proust, available either as a stand alone or compiled and revised by Joana Kilmartin included in the fourth and last volume, Time Regained, of the Modern Library edition

What Happens In Proust

The truth is that the great change brought about by

the war was in inverse ratio to the value of the minds it touched, at all

events, up to a certain point; for, quite at the bottom, the utter fools, the

voluptuaries, did not bother about whether there was a war or not; while

quite at the top, those who create their own world, their own interior life,

are little concerned with the importance of events. What profoundly

modifies the course of their thought is rather something of no apparent

importance which overthrows the order of time and makes them live in

another period of their lives. The song of a bird in the Park of Montboissier,

or a breeze laden with the scent of mignonette, are obviously matters

of less importance than the great events of the Revolution and of the

Empire; nevertheless they inspired in Chateaubriand's Mémoires d'outre

tombe [Memoirs from Beyond the Grave: 1768-1800 ] pages of infinitely greater value.

--Time Regained

Here is the passage from Chateraubriand that Proust is alluding to:

I was roused from my reflections by the warbling of a thrush perched on the highest branch of a birch. This magic sound brought my father’s lands back before my eyes in an instant. I forgot the disasters I had only recently witnessed and, abruptly transported into the past, I saw again those fields where I so often heard the thrushes whistling. When I listened then I was sad, as I am today; but that first sadness was born of a vague desire for happiness: a privilege of the inexperienced. The sadness that I experience presently comes from the knowledge of things weighed and judged. The bird’s song in the woods of Combourg spoke to me of a bliss I was sure I would attain; the same song in the park here at Montboissier reminds me of the days I have lost in pursuit of that old, elusive bliss. There is nothing more for me to learn…. Let me profit from the few moments that remain to me; let me hasten to describe my youth while I can still recall it. A sailor, leaving his enchanted island forever, writes his journal in sight of the land as it slowly slips away. It is a land that will soon be lost.

Memoirs of Chateaubriand, Vol 1

Genette notes that Proust uses the word "palimpsest" twice in the Recherche.

The smallest facts, the most trivial happenings, are only the outward signs of an idea which has to be elucidated and which often conceals other ideas, like a palimpsest.

--The Guermantes Way

My father spoke to him of it again, as often as we met him, and tortured him with questions, but it was labor in vain: like that scholarly swindler who devoted to the fabrication of forged palimpsests a wealth of skill and knowledge and industry the hundredth part of which would have sufficed to establish him in a more lucrative — but an honorable occupation, M. Legrandin, had we insisted further, would in the end have constructed a whole system of ethics, and a celestial geography of Lower Normandy, sooner than admit to us that, within a mile of Balbec, his own sister was living in her own house; sooner than find himself obliged to offer us a letter of introduction, the prospect of which would never have inspired him with such terror had he been absolutely certain — as, from his knowledge of my grandmother’s character, he really ought to have been certain — that in no circumstances whatsoever would we have dreamed of making use of it.

--Swann’s Way

Swann in Love the Vinteuil Sonata; the carriage trip with Odette and her camelias.

Place Names: the Name

The people who frequent the Champs-Élysées

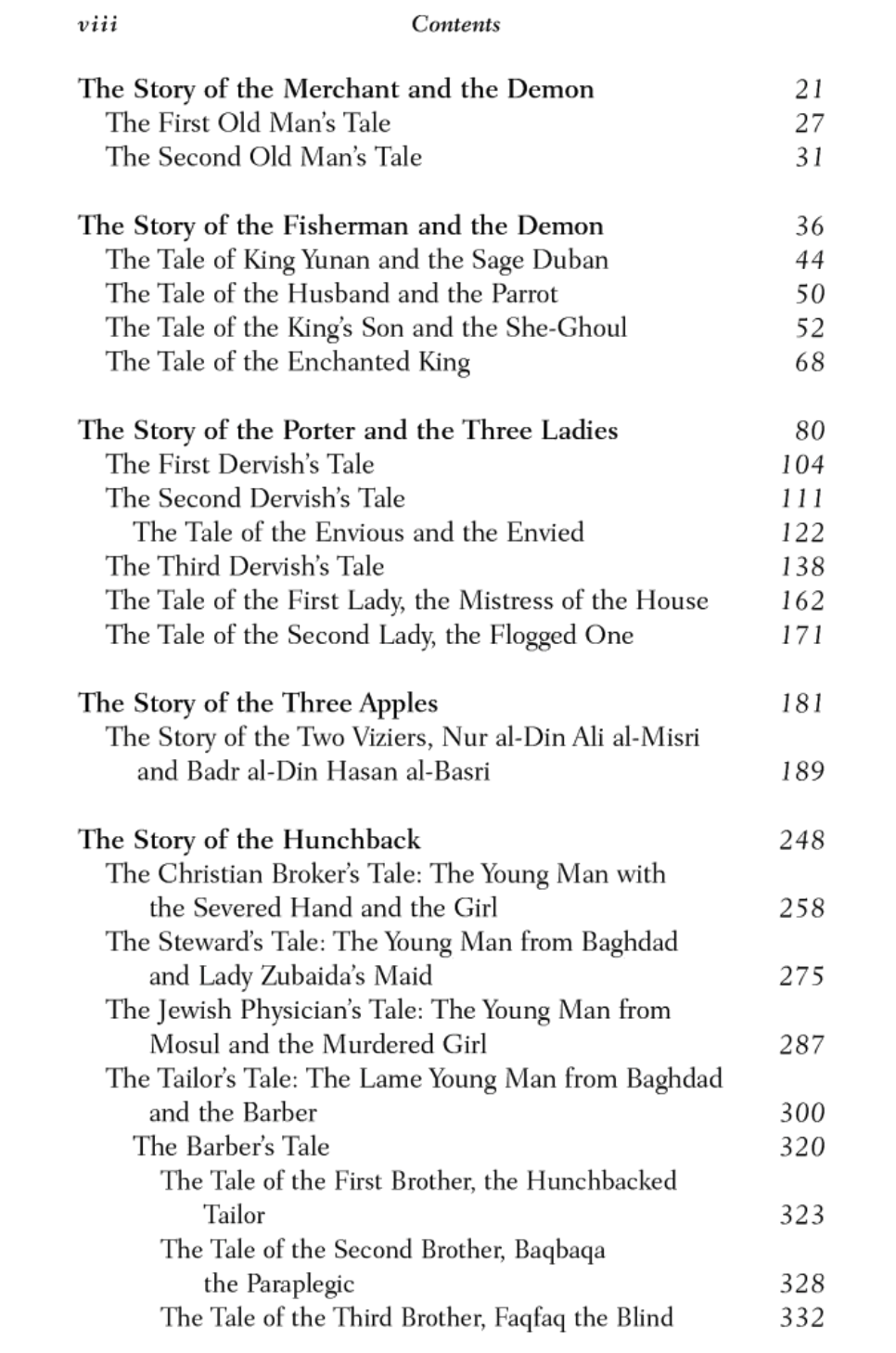

The particular characteristic of the exordium of the Recherche is obviously its multi-

plication of memory-created instances, and consequently its

multiplication of beginnings, among which each (except the last)

can seem afterward like an introductory prologue. First begin-

ning (absolute beginning): "For a long time I used to go to bed

early ..." Second beginning (ostensible beginning of the au-

tobiography), five pages later: "At Combray, as every afternoon

ended ..." Third beginning (appearance on stage of involun-

tary memory), twenty-six pages later: "And so it was that, for a

long time afterwards, when I lay awake at night and revived old

memories of Combray ..." Fourth beginning (resumption after

the madeleine, real beginning of the autobiography), four pages

later: "Combray at a distance, from a twenty-mile radius ..."

Fifth beginning, one hundred and seven pages later: ab ovo,

Swann in love (an exemplary novella if there ever was one, ar-

chetype of all the Proustian loves), conjoint (and hidden) births

of Marcel and Gilberte ("We will confess," Stendhal would say

here, "that, following the example of many serious authors, we

have begun the story of our hero a year before his birth." Is not

Swann to Marcel, mutatis mutandis and, I hope, with nothing

untoward in mind, what Lieutenant Robert is to Fabrice del

Dongo?) 16 — fifth beginning, thus: "To admit you to the 'little

nucleus,' the 'little group,' and 'little clan' at the Verdurins' ..."

Sixth beginning, one hundred and forty-nine pages later:

"Among the rooms which used most commonly to take shape

in my mind during my long nights of sleeplessness. . ." im-

mediately followed by a seventh and thus, as it should be, a final

beginning: "And yet nothing could have differed more utterly,

either, from the real Balbec than that other Balbec of which I had

often dreamed ..." This time, the movement is launched: after

this it will never stop.

--Gérard Genette on the seven beginnings of Swann's Way

The first page of Swann's Way

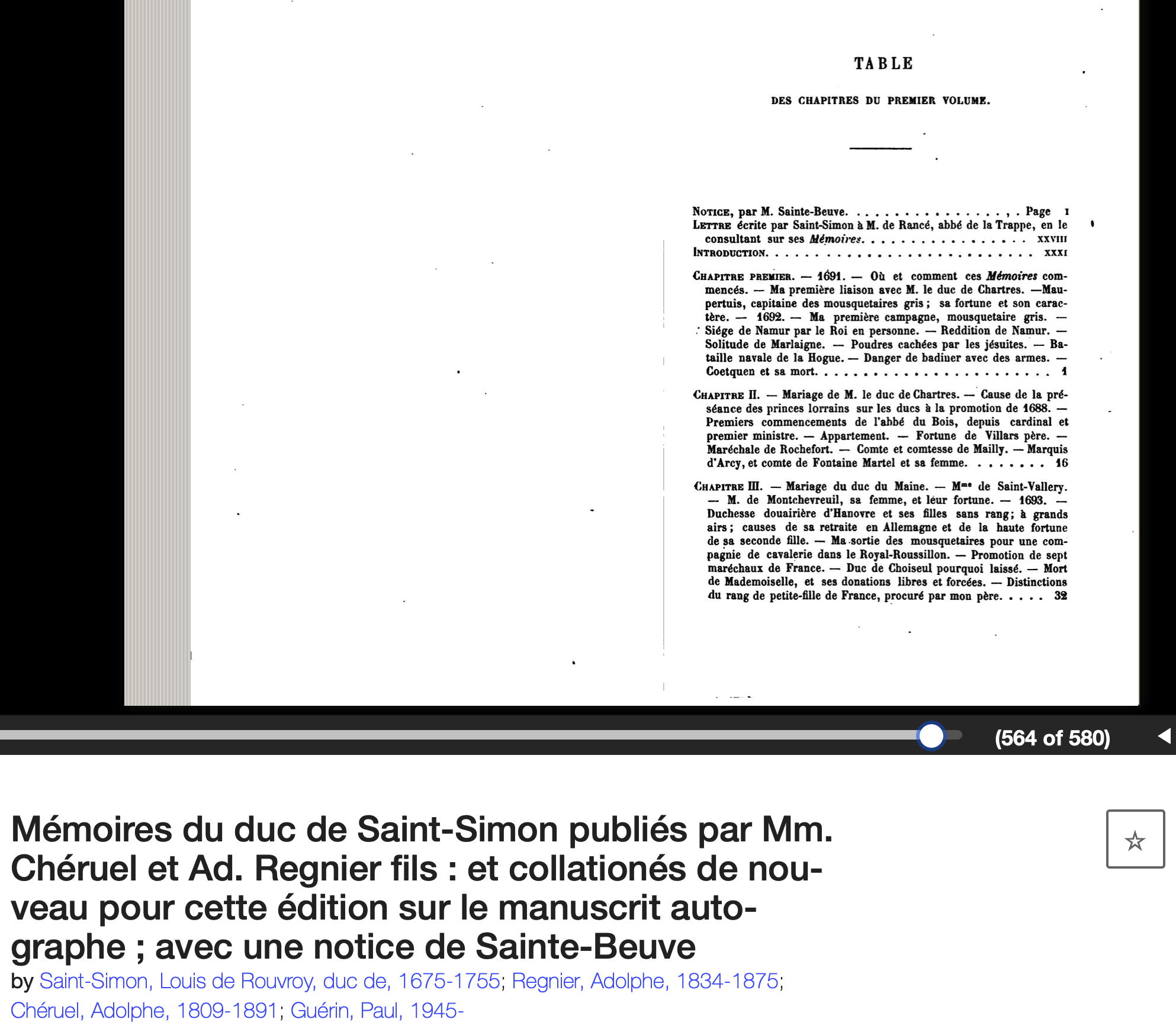

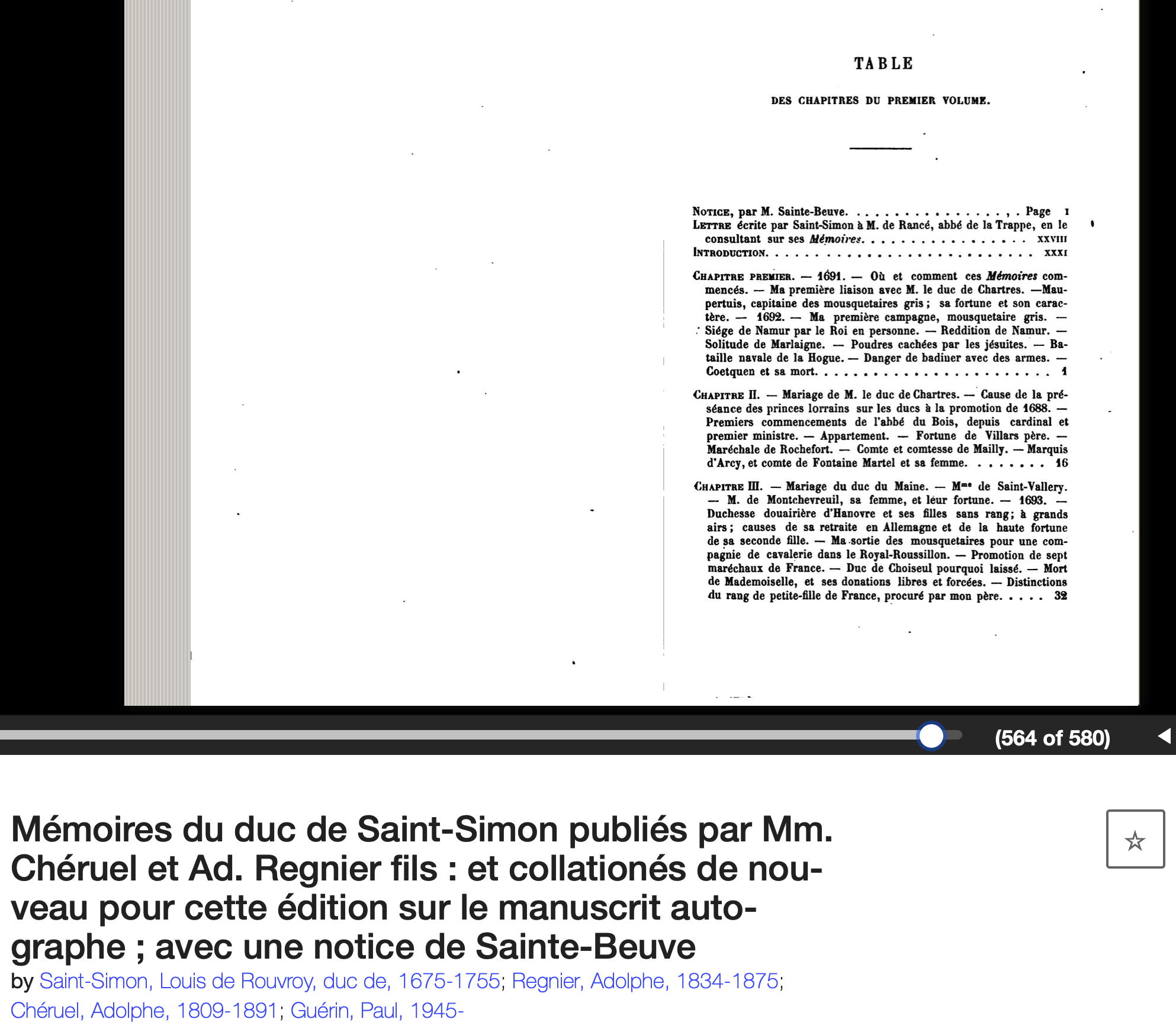

MARCEL PROUST, PASTICHES ET MÉLANGES

- JOURNÉES

DE LECTURE TABLE DES MATIÈRES PASTICHES

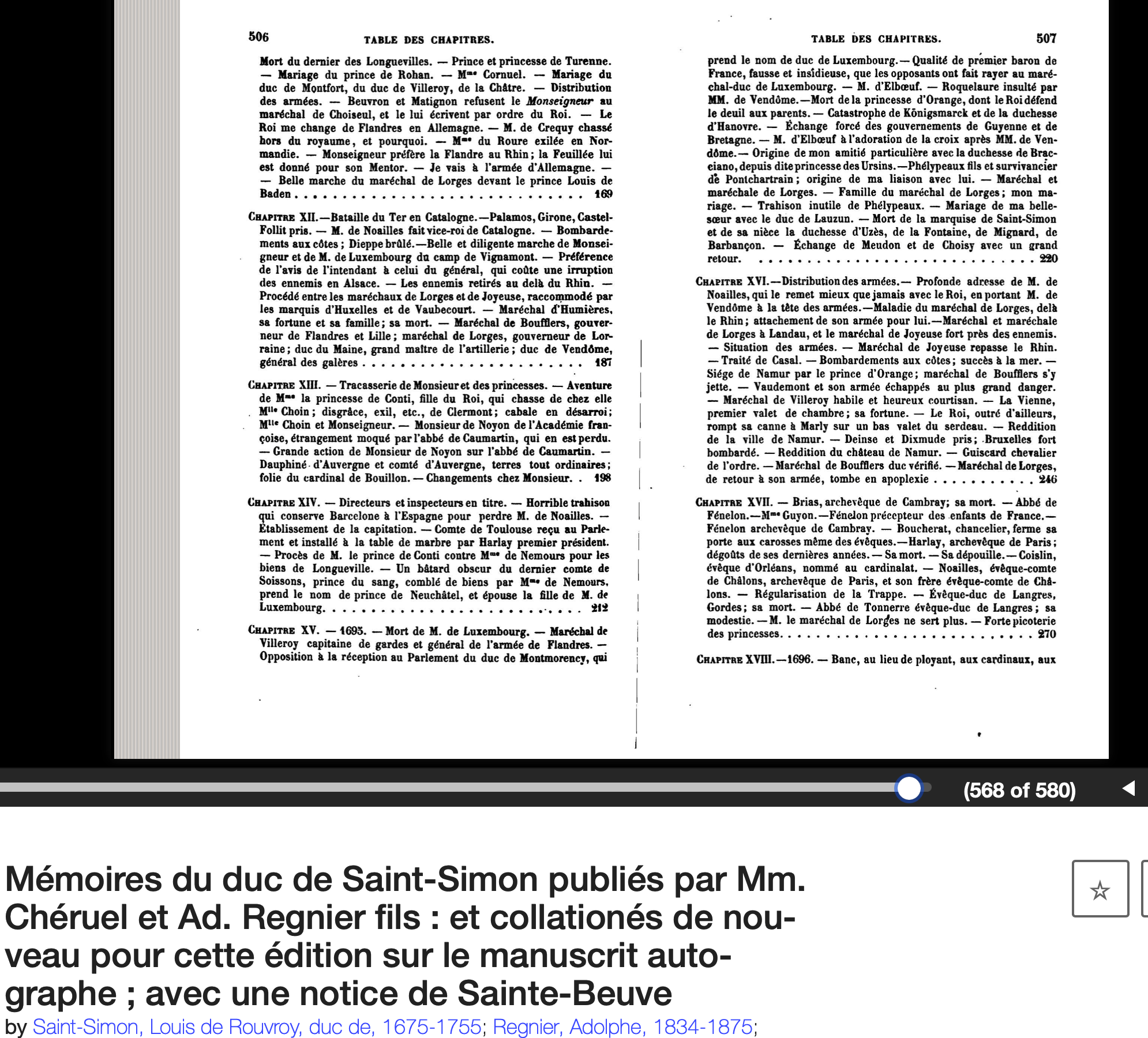

L'AFFAIRE LEMOINE I. Dans un Roman de Balzac II. L'«Affaire Lemoine», par Gustave Flaubert III. Critique du roman de M. Gustave Flaubert sur l'«Affaire Lemoine», par Sainte-Beuve, dans

son feuilleton du Constitutionnel IV. Par Henri de Régnier V. Dans le «Journal des Concourt» VI. L'«Affaire Lemoine», par Michelet VII. Dans un feuilleton dramatique de M. Émile Faguet VIII. Par Ernest Renan IX. Dans les Mémoires de Saint Simon MÉLANGES EN MÉMOIRE DES ÉGLISES ASSASSINÉES I. Les Églises sauvées. Les Clochers de Caen. La

Cathédrale de Lisieux.

Journées en Automobile II. Journées de Pèlerinage.

Ruskin à Notre-Dame d'Amiens, à Rouen, etc. III. John Ruskin

La Mort des Cathédrales SENTIMENTS FILIAUX D'UN PARRICIDE

JOURNÉES DE LECTURE

Montcrieff translation on the left (the title "Overture" is his) and Davis translation on the right.

"In many of his comments on Proust, Barthes seems to warn against

an excess of seriousness. Good readings, of this author at least, he suggests,

are light, partial and tangential. Getting the book right is a matter

of seeing the mighty body of the text aslant and askew.“D’une lecture

à l’autre, on ne saute jamais les mêmes passages” (From one

reading to another, one never skips the same passages), he writes in Le

Plaisir du texte (1???). Besides, Proust’s entire undertaking is in a sense

an exercise in idling, he adds in one of the interviews collected

posthumously as Le Grain de la voix (1???), and it would not be in

keeping with the book’s delicious associative textures to read it in an

other than idly pleasure-seeking frame of mind. Repudiating the notion

that he might be thought a Proust “specialist,” he writes, again in

Le Plaisir du texte, “Proust, c’est ce qui me vient, ce n’est pas ce que

j’appelle; ce n’est pas une ‘autorité’” (Proust is that which comes to

me, not that which I call forth; he is not an “authority”). Only scholars

and specialists would want to turn the reading of Proust prematurely

towards long labour and goal-directed linearity. “Je ne suis pas

‘proustien’” (I am not a “Proustian”), he repeats elsewhere in Le Grain

de la voix."

Malcolm Bowie, "Barthes on Proust," The Yale Journal of Criticism, Volume 14, Number 2, Fall 2001, pp. 513-518; to p. 513.

Roland Barthes, "Proust Longtemps . . . "

Roland Barthes, "Proust and Names"

Many people try to read Swann's Way presumably because it is such a famous novel. Most of them fail. Why? Partly because the novel is very difficult. It has famously long sentences. There is little by way of plot. Pages and pages are devoted to a small incident. For descriptions of examples, see this humorous report:

I think it is safe to say that every reader will share this critic's experience, though not his exasperated response. What is going on?

In most classes on a novel, students are told to read the novel the same way they would read any book, namely, from beginning, starting on the first page, and ending on the last. A critical edition would supply annotations, and guides to the Recherche include summaries, quotations, and commentaries. Everything is directed toward basic reading comprehension. This kind of reading is criticism at it its most basic, and although limited, it has the benefit of being very close to the text. we will be doing what Gérard Genette calls "structured reading." Instead of reading the Recherche head on by reading it in order, we will overcome its difficulty by reading it out of order, breaking up Swann's Way with digressions, so to speak, into literary theory (mostly essay and boook chapters by Genette), and leaping ahead to the last novel, Time Found Again, aka Time Regained. We will read also read scenes from other novels related to the title of this course that bear on the novel's completion and incompletion. By proceeding in this eccentric manner, we will be able to read the Recherche in two ways, attending not only to any one of the seven novels we are reading but also gaining a sense of that novel relates to the Recherche as a whole. And we will then be in a positition to ask not only what is Proustian but the more interesting and challenging question, What is Proustian about Proust?

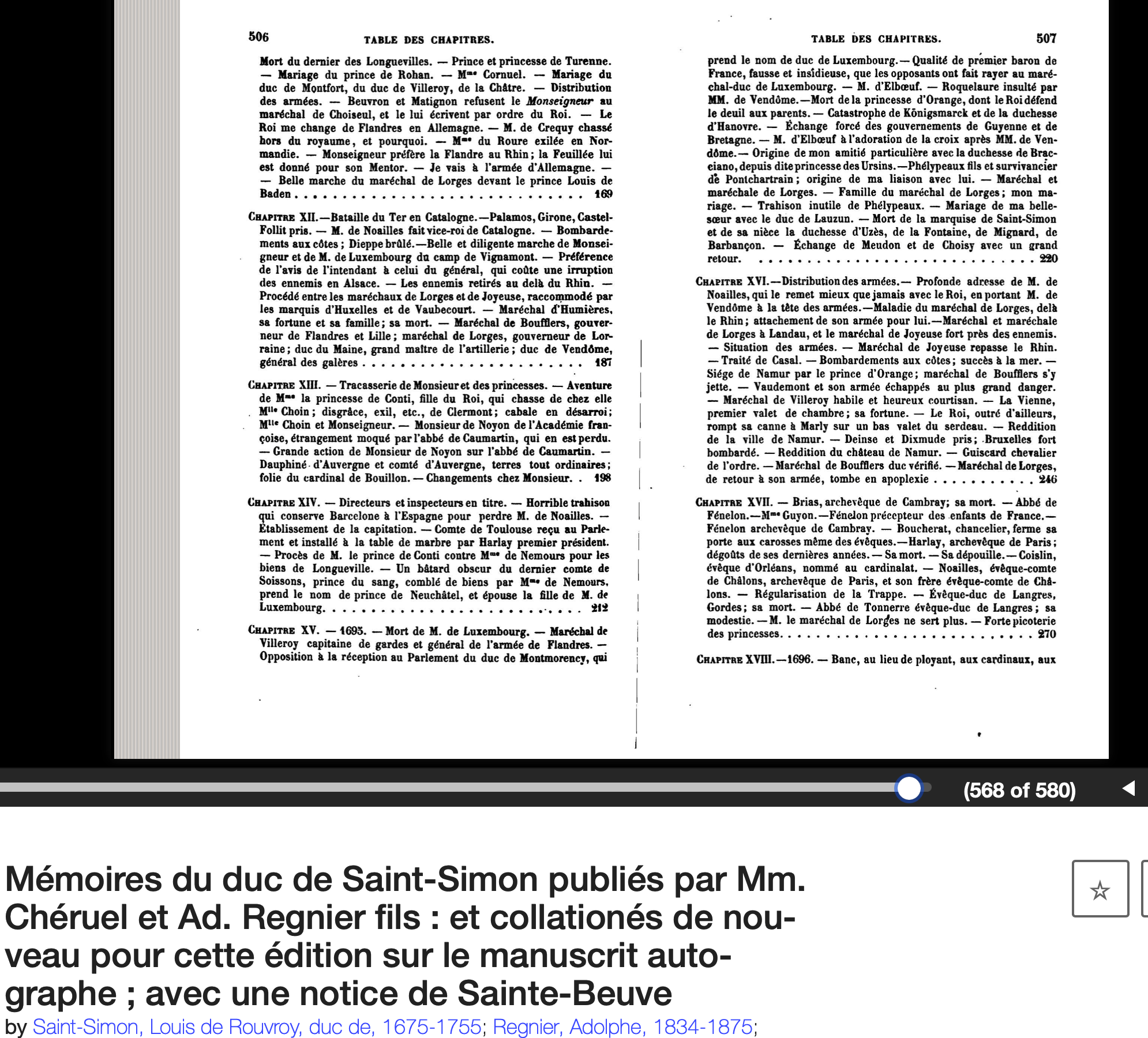

At the end of the semester I’ll have each trace a character through all of the novel including the parts we skipped and give a synopsis in class. They’ll also have to provide a table of contents to their synopsis like the Proust does at the end of each volume. And I’ll assign different plot summaries for each volume. Take maybe the last four weeks. And in the two hour block I would present previously unread passages we can read aloud and then close read.

NOTE BENE: THIS IS LARGELY AN IMMERSIVE COURSE IN MONOTASKING, READING THREE VOLUMES OF MARCEL PROUST'S FAMOUS NOVEL IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME, ONE OF THE GREATEST OF ALL NOVELS, FROM THE VIEWPOINT OF GéRARD GENETTE'S WORK ON NARRATOLOGY. READING PROUST WILL BE DEEPLY REWARDING. IT WILL ALSO BE A LABOR INTENSIVE, TIME CONSUMING PROCESS THAT DEMANDS YOUR TOTAL CONCENTRATION FOR LONG PERIODS OF TIME. WORK WILL BE DUE BEFORE EACH CLASS MEETING. To do the assigned listenings, pass the quizzes at the beginning of each class, and write thoughtful discussion questions on the readings, you will have to spend five to six hours a week OUTSIDE of class preparing for class discussion. YOU WILL ALSO HAVE TO READ THE TEXT CLOSELY, PAYING ATTENTION TO CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT, SENTENCE STRUCTURE, VOCABULARY, THE FLUID MODERNIST STRUCTURE OF THE NOVEL. (It's known as a roman-fleuve, or series of novels that make up a single, larger novel; "fleuve" in French means "river" or "stream.") INFORMATION ABOUT THE AUTHOR OR THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDOF THE NOVEL MAY BE FOUND ON WIKIPEDIA. ALTHOUGH WE WILL CONSIDER FROM TIME TO TIME WHAT MAY HAVE BEEN PROUST'S (INVOLUNTARY) BLUNDERS, WE WILL PRIMARILY DISCUSS THE NOVEL AND ONLY THE NOVEL IN ORDER TO UNDERSTAND IT AND Gérard Genette's WORK ON NARRATOLOGY that is primarily devoted to Proust. See Genette's Narrative Discourse, p. 124; 184.

Novel of ideas / philosophy as experience

C'était, en effet, sous cette forme trop simple que je jugeais mon aventure avec Albertine, maintenant que je ne voyais plus cette aventure que en dehors.

Le Temps retrouvé (Pléiade edition) Vol. 4, p. 285

"It was in this too simple form that I judged my affair with Albertine at a time when I only

saw it from the outside."

----Time Regained, Trans. Stephen Hudson

"This was the excessively simple light in which I regarded my adventure with Albertine, now that I saw it only from outside."

Time Regained, Trans. C. K. Montcrieff et al p. 23

"It was, indeed, in this over-simplied form that I regarded my adventure with Albertine, now that I could only

see it from the outside."

--Finding Time Again, Trans. Ian Patterson, p. 13

Learning French Pronunciation (Proust translated English into French and was very sensitive to the sounds of words.)

Remembrance of Things Past V 2. The Guermantes way. Cities of the plain (1981)

Trans. Scott Montcrieff; Terence Kilmartin

https://www.deepl.com/translator

Key concepts of narratology: focalization / Genette, Gérard (1972). "Discours du récit." G. Genette. Figures III. Paris: Seuil, 67–282 / Narrative Discourse: An Essay on Method, pp. 189-94; Gérard Genette on narrative and discourse in "Boundaries of Narrative," Trans. Ann Levonas. New Literary History, Autumn, 1976, Vol. 8, No. 1, Readers and Spectators: Some Views and Reviews (Autumn, 1976), pp. 1-13; to pp. 8-12; free indirect style / narrative voice: who is speaking? "Voice in Narrative Discourse: An Essay on Method, pp. 212-62.

Gérard Genette, "Fictional Narrative, Factual Narrative," Trans. Nitsa Ben-Ari, Brian McHale. Poetics Today, Vol. 11, No. 4, Narratology Revisited II (Winter, 1990), pp. 755-774.

"In arguing against short commentaries on individuall passages from Remembrance of Things Past,

one might say that with Proust's bewilderingly rich and intricate creation the reader is more in need of an orienting

overview than of something that entangles him still more deeply in

details-from which the path to the whole is in any case difficult and

laborious. This objection does not seem to me to do justice to the matter.

We are no longer lacking in grand surveys of Proust. In Proust, however,

the relationship of the whole to the detail is not that of an overall

architectonic plan to the specifics that fill it in: it is against precisely that,

against the brutal untruth of a subsuming form forced on from above,

that Proust revolted.

. . . I do not want merely to point out the ostensible high points

of his work, nor to advance an interpretation of the whole that would at

best simply repeat the statements of intention which the author himself

inserted into his work. Instead, I hope through immersion in fragments

to illuminate somethi ng of the work's substance, which derives its unforgettable

quality solely from the coloring of the here and now. I believe I

will be more faithful to Proust's own intention by proceeding in this way

than by trying to distill it and present it in abstract form.

--Theodor Adorno, "On Proust," Notes to Literature Vol 2, 317

"One should never bear grudges against people, never judge them by the memory of one unkind act, for we can never know all the good resolves and effective actions of which their souls may have been capable at another time. And so, even from the simple point of view of foresight, we make mistakes. For no doubt the bad pattern we observed on that one occasion will recur. But the soul is richer than that, has many other patterns which will also recur in the same man, yet we refuse to take pleasure in them because of one piece of bad behavior in the past."

The Prisoner, trans. Carol Cook, p. 311

Swann in Love (Oxford World's Classics, 2018) Bryan Nelson (Translator)Marcel Proust, Swann in Love, Swann's Way: In Search of Lost Time, Vol. 1 (Penguin, 2004) Lydia Davis (Translator )

REQUIRED LISTENING: (Listen to chapters 5-6 of the original, unrevised Montcrieff translation of Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time Complete Volumes read by John Rowe) Proust, Swann's Way, Modern Library editionMarcel Proust, Combray, Swann's Way (the original Montcrieff translation: Susanna Lee, Ed. Norton Critical Editions, 2013)

Proust, Swann's Way, Modern Library editionMarcel Proust, Combray, Swann's Way (the original Montcrieff translation: Susanna Lee, Ed. Norton Critical Editions, 2013)

In Class Exercises: Listening comprehension: transcribe what you hear and punctuate it as well as you can.Reading Comprehension: copy what you read word for word.Marcel Proust, The Overture, Swann's Way (Montcrieff invented the "Overture," combining the opening about Marcel's insomnia and the famous madeleine episode.)Where does one passage end and another begin?Marcel Proust, Swann's Way, Ch1_2 Trans. Lydia DavisRecommended Reading:Marcel_Proust, On_Reading

Marcel Proust, The Lemoine Affair. Read the linked pdf and read for free pp. 9-22 online here with "look inside." (TRANSLATOR CHARLOTTE MANDELL)The narrator's involuntary memories of life at Combray, the most notable being his insomnia anda madeleine dipped in a cup of tea. But see Samuel Beckett (pp. 32-35) on listening to the Venteuil Sonata as more central than the madeleine episode. "Intermintencies of the Heart" (in n is the most important part of the novel, according to Beckett. It includes an involuntary memory of the grandmother. Who is speaking? The "I" that is not "me." Free Indirect Dicourse"The number of pawns on the human chessboard being less than the number of combinations that they are capable of forming, in a theatre from which all the people we know and might have expected to find are absent, there turns up one whom we never imagined that we should see again and who appears so opportunity that the coincidence seems to us providential, although no doubt some other coincidence would have occurred in its stead had we been not in that place but in some other, where other desires would have been born and another old acquaintance forthcoming to help us to satisfy them.”

The Guermnates Way

Proust and the Past and Imperfect Tenses:

The first sentence is one of the very few sentences written in the past tense (passé composé)

“Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure."

“For a long time I used to go to bed early.” Scott Moncrieff-Terence Kilmartin

"For a long time, I went to bed early." Lydia Davis

"For a long time I would go to bed early."

“Time was when I always went to bed early." James Grieve; Richard Howard (translating Roland Barthes' "Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.")

“Time and again, I have gone to bed early.” Richard Howard

See Samuel Beckett on listening to the Vinteuil Sonata as being more central than the madeleine episode. "Intermintencies of the Heart" (in Sodom and Gomorrah) is the most important part of the novel, according to Beckett. It includes an involuntary memory of the grandmother.

Inspirations for the imaginary Vinteuil sonata:

César Franck-Violin Sonata in A Major (Complete)

A la recherche de la sonate de Vinteuil - Julie Depardieu

Franck, Debussy, Fauré, Wagner, Saint-Saens, Gabriel Pierné, Renal Duan

A Proust Playlist

Antoine Compagnon, "Proust Between Two Centuries"

In Search of Last Time considered as a Bildungsroman--the narrator discovers his vocation as a writer; autobiography; fiction (Marcel the "I," or narrator is not Marcel the "me," or the writer; a soap opera (scheming and social climbing); a satire of the Belle Époque, French High Society (circa. 1880-1914), and more.

Journal entries: I will ask you to keep a journal of your listening / readings of Swann's Way. Keep all entries in one word docoument. Cut and paste three passages from the assigned reading and put them into your document by 5:00 p.m. You will see that Proust's "Synopsis" breaks the novel up into small parts and gives them each a short description, kind of like a cross between a table of contents and an index. Break up the novel your own way based on either the sentence or the narrative structure and provide brief desriptions of your own for them. Each journal entry is due each Friday by 5:00.

DQs are due Mondays and Wednedays by 5:00 p.m. along with three BIG WORDS. Email all work for the course to me at [email protected] I want you to learn how to write your DQs in a Proustian style over the semester. As you write about the novel, imagine you are writing an autobiography and a novel about your memories of reading in the style of the novel. When we finish the semester, you will have a collection of quotations, fragments of your search for time you lost reading the three assigned volumes of Proust's seven volume novel.

First Paper Topic

What is a typo? What is a Freudian Slip?

--Jacques Derrida, "De Tout," in The Post Card

What is an author's blunder?

--Richard Peavar, "The Translator's Inner Voice," in Translating Music, pp. 31-3.

"Every reader is, while he is reading, the reader of his own self."

Recherche

As well as being famously long, Proust is also often thought of as boring. Is this true, and will we get through this first volume?

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B085DQB8YQ/

Georges Bataille, Proust

Roland Barthes, "Longtemps . . . "

Gérard Genette Fiction and Diction

Did Gide Read Proust? NY Times

Gilles Deleuze, Proust and Signs

Gérard Genette, Essays in Aesthetics

Gérard Genette, Mimologics

Gérard Genette, "Proustian Paratexte"

Gérard Genette, "Boundaries of Narrative," trans. Ann Levonas New Literary History, Autumn, 1976, Vol. 8,

Gérard Genette, Figures III

Emmanuel Levinas "The Other in Proust"

Leslie Hill, "Reading Proust "

Paul_Valery, Monsieur Teste

Marcel Proust, On Reading

Barthes, Proust

Auerbach, Mimesis Proust

Adorno, On Proust

Adorno, Proust Commentaries

Gérard Genette, "Paul Valery Literature as Such"

TENTATIVE SCHEDULE (Please expect minor adjustments to be made in the schedule from time to time; all changes will be announced both in class and on the class email listserv.)

AUGUST 24: No Writing Off the Writer, However Bad

Sainte-Beuve championed a form of biographical criticism that saw texts as morally and intellectually inseparable from their writers. Sainte-Beuve . . . rank[ed] Bernard, Vinet, Molé, Verdelin, Meilhan, and Azyr among the great writers of his time, . . . dismiss[ed] Baudelaire and Balzac as vulgar and Hugo as overly political. History has not been on Sainte-Beuve’s side, and neither was Proust. A la recherche, the novel that grew out of [Contre Sainte-Beuve] this early piece of literary criticism, persuasively refutes Sainte-Beuve’s method by bringing into contrast the sometimes sordid lives of its characters and the emotional nuance of their experiences of the world.

Marcel Proust, Contre Saint-Beuve

Diaectical contradiction of Proust's criticism of Saint-Beuve, Walter Benjamin's "The Image of Proust":

Walter Benjamin, "On the Image of Proust, in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings Volume 2 part 1 1927-1930, 237-47

"Read as the straightforward discursive text it pretends to be, the essay falls short of the demands currently made on literary criticism. It presents itself as a loose succession of biographical anecdote and casual commentary, which attempts to penetrate 'to the heart of the Proustian world' (p. 365), by giving the reader apparent access, through the literary work, to the society, the philosophical thought, and the author behind the text. Yet the repeated contradiction and discrepancy that arise from these attempts at penetration offer no sure key to the mastery of Proust's work, and the hermeneutic rigor which the reader of criticism has come to expect remains conspicuously lacking.

It would be of the text to its own self contradiction. Yet if one writes oneself into the logic of Benjamin's metaphorical web, the text itself accounts for the discrepancies which seem to unfold. The theoretical statement which arises out of such a reading, as oblique and self-negating as it may have to be, may violate the conventional notions of the literary text, the critical text and the basis for their distinction, but violates them with rigor. Benjamin, like others before him, dissolves an old genre (literary criticism) in order to found a new one, which combines fiction and commentary."

Carol Jacobs, "Walter Benjamin: Image of Proust," MLN Vol. 86, No. 6, Comparative Literature (Dec., 1971), pp. 910-932

Note: Don't go with dogma, just way. Be on the look out for the dialectical contradiction that enables you to rethink your earlier take.

Consider the narrator's account of Morel in Sodom and Gomorrah. Morel is not "wicked through and through" but "full of contradictions," a phrase the narrator uses twice. The narrator compares Morel to a book from the Middle Ages and to sheets of papers. Morel's cultural literacy is the measure of his contradictions: he can quote a line from a letter to Chateaubriand--"work, work, and achieve reknown" and a "stupid" maxim.

Moral imagination is not just cancel (stupid) don't cancel (smart) but exploring ways knowledge of a person (character) registers the range and limits of that character's morality. Morel is dirven by money but is not entirely evil. But his contradictions hardly excuse him. They are a kind of weak excuse that allows the narrator to enjoy telling us how bad Morel is. The narrator's own moral imagination, its range and its limit are defined by the narrator's account of Morel. Several characters know one or two expressions. That's a recurrent joke the narrator uses.

After the radio broadcast of "Short Commentaries on Proust," I received

letters of protest about my allegedly excessive use of foreign words

for the first time since my youth . I looked through the text of the talk

and found no unusual number of foreign words in it, although people

may have held some French expressions that arose in connection with the

French subject matter against me. Thus I can hardly explai n the outraged

correspondence except through the contrast between literary texts and

their interpretation . With great narrative prose, interpretation easily

takes on the coloration of the foreign word. The syntax may sound more

foreign than the vocabulary. Attempts at formulation that swim against

the stream of the usual linguistic splashing in order to capture the

intended matter precisely, and that take pains to fit complex conceptual

relationships into the framework of syntax, arouse rage because they

require effort. The person who is naive about language will ascribe the

strangeness of such writing to the foreign words, which he holds responsible

for everything he doesn't understand even when he is quite familiar

with the words. Ultimately, what is going on is largely a defense against

ideas, which are imputed to the words; the blame is misdi rected. I once

tested this in America when I gave a disconcerting lecture to an emigre

association to which I belonged, a lecture from which I had carefully

eliminated every foreign word. Nevertheless, the lecture met with precisely

the same opposition I am now encountering in Germany. I have

had this kind of experience si nce my childhood , when old Dreibus, a

neighbor who lived on my street, attacked me in a rage as I was

conversing harmlessly with a comrade in the streetcar on my way to

school: "You goddamned little devil! Shut up with your High German

and learn to speak German right. " I had scarcely recovered from the

fright Herr Dreibus gave me when he was brought home in a pushcart

not long afterwards, completely i ntoxicated, and it was probably not

much later that he died. He was the first to teach me what Ra"cu"e [from

the French , meaning rancor or spite] was, a word that has no proper

native equivalent in German, unless one were to confuse it with the word

Resenttiment [resentment], a word currently enjoying an unfortunate

popularity in Germany but which was likewise imported rather than

invented by Nietzsche. In short, it is a case of sour grapes: outrage over

foreign words is to be explained in terms of the psychic state of the one

who is angry for whom some grapes are hanging too high up. .. .

I have chosen the examples for this analysis from a text of my own, not

because I consider the text exemplary but because I am more aware of the decisive considerations and can explain them better

than those of other authors. I will refer intentionally to the "Short

Commentaries on Proust" that brought the protests.

Adorno, "Words from Abroad," in Notes to Literature

In arguing against short commentaries

on individuall passages from Remembrance of Things Past, one might say that

with Proust's bewilderingly rich and intricate creation the reader is more in need of an orienting

overview than of something that entangles him still more deeply in

details-from which the path to the whole is in any case difficult and

laborious. This objection does not seem to me to do j ustice to the matter.

We are no longer lacking in grand surveys of Proust. In Proust, however,

the relationship of the whole to the detail is not that of an overall

architectonic plan to the specifics that fill it in: it is against precisely that,

against the brutal untruth of a subsuming form forced on from above,

that Proust revolted. Just as the temperament of his work challenges

customary notions about the general and the particular and gives aesthetic

force to the dictum from Hegel's Logic that the particular is the general

and vice versa, with each mediated through the other, so the whole,

resistant to abstract outlines, crystallizes out of intertwined individual

presentations. Each of them conceals within itself constellations of what

ultimately emerges as the idea of the novel. Great musicians of Proust's

era, like Alban Berg, knew that living totality is achieved only through

rank vegetal proliferation. The productive force that aims at unity is

identical to the passive capacity to lose oneself in details without restraint

or reservation. In the inner formal composition of Proust's work, however-

and it was not only on account of its long, obscure sentences that

Proust's work struck the Frenchmen of his time as so German-there

dwells, Proust's primarily optical gifts notwithstanding and with no

cheap analogy to composition intended, a musical impulse. It is evi

denced most emphatically in the paradox that Proust's great theme , the

rescue of the transient, is fulfilled through its own transience, time. The

durle the work investigates is concentrated in countless moments, often

isolated from one another. At one point Proust extols the medieval

masters who i ntroduced ornaments into their cathedrals so hidden that

they must have known that no human being would ever set eyes on them.

Such unity is not one arranged for the human eye but rather an i nvisible

unity in the midst of dispersion, and it would be evident only to a divine

observer. Proust should be read with the idea of those cathedrals in

mind, dwelling on the concrete without grasping prematurely at something

that yields itself not directly but only through its thousand facets.

This is why I do not want merely to point out the ostensible high points

of his work, nor to advance an interpretation of the whole that would at

best simply repeat the statements of intention which the author himself

inserted into his work. Instead, I hope through immersion in fragments

to illuminate somethi ng of the work's substance, which derives its unforgettable

quality solely from the coloring of the here and now. I believe I

will be more faithful to Proust's own intention by proceeding in this way

than by trying to distill it and present it in abstract form.

The process by which the novel unfolds is the description of the path traveled by these images.

That path has stations, like the three passages about Oriane Guermantes: the first confrontation

of her image with empirical reality in the church at Combray, then her rediscovery

and modification while the narrator's family is living in the Duchess' house in Paris, in her immediate proximity, and

finally the fixing of her image in the photograph the narrator sees at the home of his friend Saint-Loup.

Theodor Adorno, "Short Commentaries on Proust," in Notes to Literature Vol 1.

The story Proust tells is that of happiness unattained or endangered.

At the top of the list of his psychological subjects stands jealousy,

whose rhythm is recurrent and establishes the unity within the multiplicity.

To the question of the possibility of happiness Proust responds by

depicting the impossibility of love. Being fully oneself, absolutely differentiated,

means at the same time isolation and profound alienation.

The unfettered potential, and readiness, for happiness hinders one's own

fulfillment.

Thus in Proust, whom the French, with good reason, frequently experience

as German, everything individual and transient becomes null,

as in Hegelian philosophy. The polarity of happiness and transience directs

him to memory. Undamaged experience is produced only in memory,