-

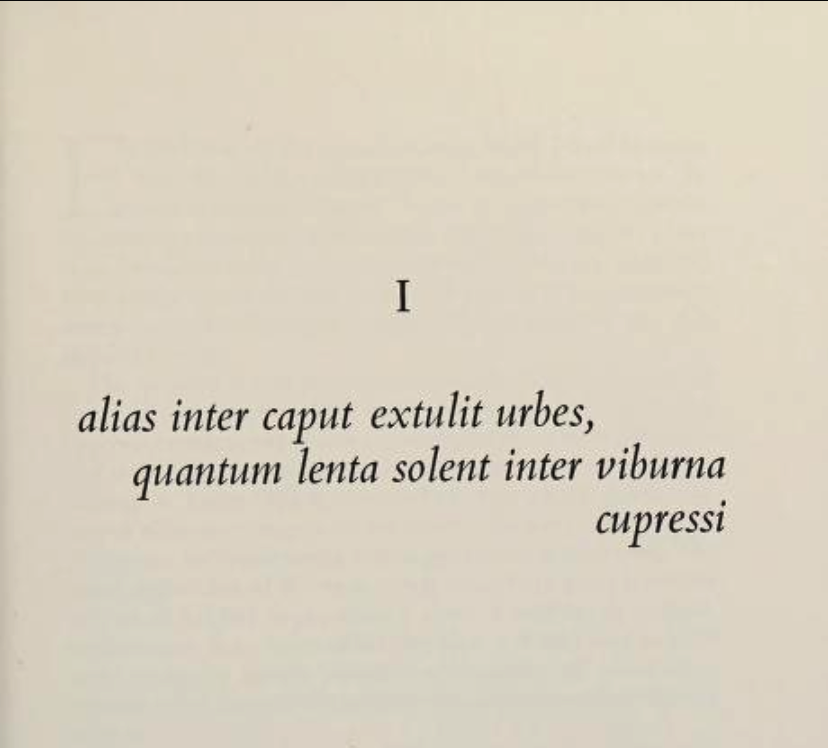

Susan J. Wolfson, Chapter 6 "Still Romancing: The Eve of St. Agnes; a dream-sonnet; Labelle dame" Reading John Keats, Princeton University, New Jersey, pp. 72-86

I designed this course myself and am looking forward to teaching it this semester. If you have a question or a problem in urgent need of resolution, please contact me in class or at [email protected]. (I am the manager.)

Post Your DQs and BIG WORDS BOTH on Canvas AND on this google document.

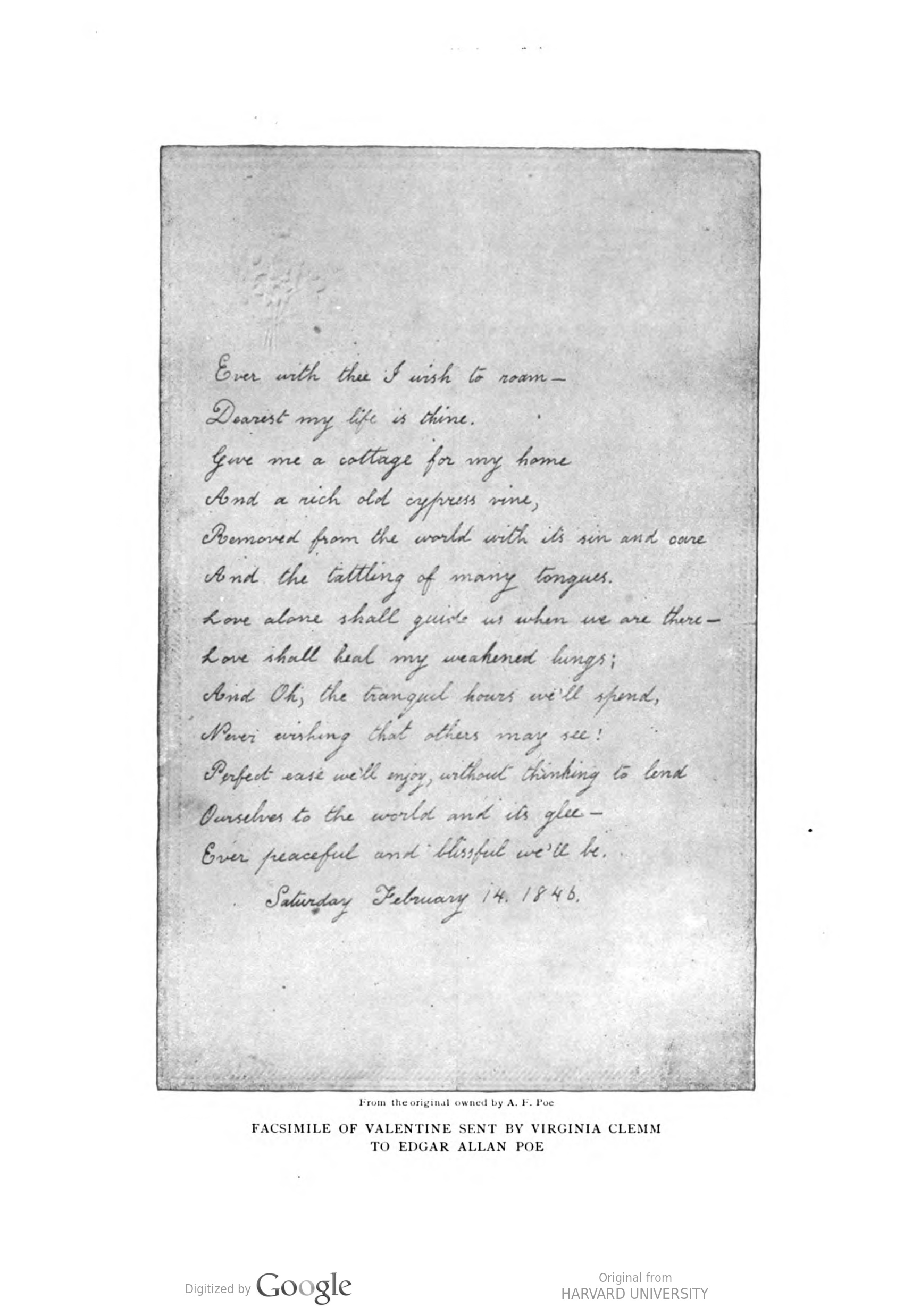

“But not to the degree to contaminate—”

“To contaminate?”—my big word left her at a loss. I explained it. “To corrupt.”

--Henry James, The Turn of the Screw (1892)

Albert Camus, "Appendix: Hope and the Absurd in the Work of Franz Kafka from The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays"

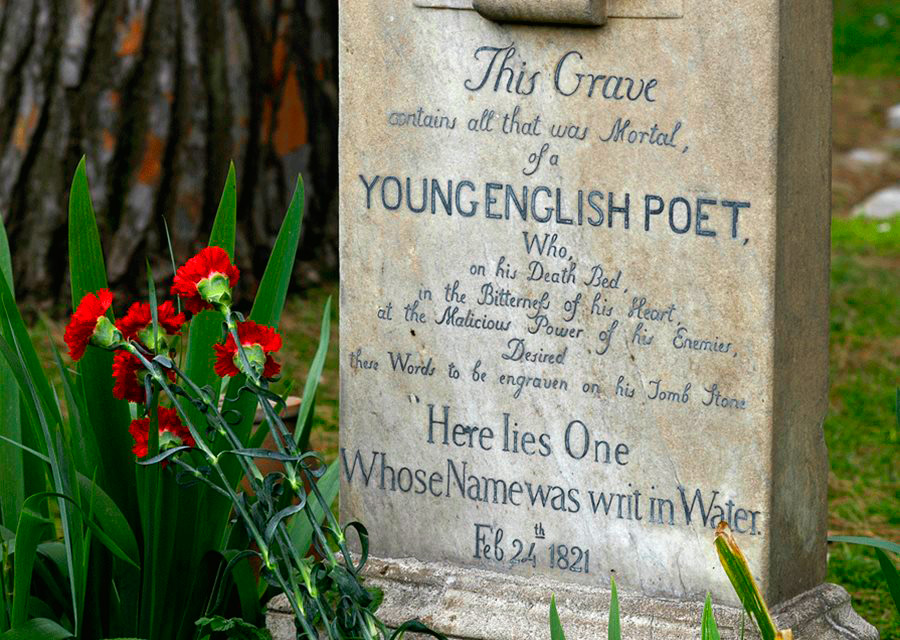

All recommended readings are optional. First day of class. Let's read Keat's Romantic poem "Bright Star" aloud and then discuss it to discover what kind of formal attention a close reading involves. Then let's watch Abbie Cornish, playing Fanny Brawne, deliver "Bright Star" very emotionally, Brawne's heart broken into a thousand pieces by Keats' death (he was just 25), at the end of Jane Campion's wonderful film, Bright Star (2009). If we are moved, moved perhaps even to weep, how does Cornish tap in the language and form of the poem to move us so deeply? What is Keats doing with words to leave us his poem as a resource for living?

JOHN KEATS Bright Star Soundtrack- 06--Bright Star-Abbie Cornish / "Bright Star" (2009) ending

“Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art”

Susan Wolfson's comments, p. 140

TENTATIVE SCHEDULE (Please expect minor adjustments to be made in the schedule from time to time; all changes will be announced both in class and on the class listserv.)

YOUR FIRST ASSIGNMENT:

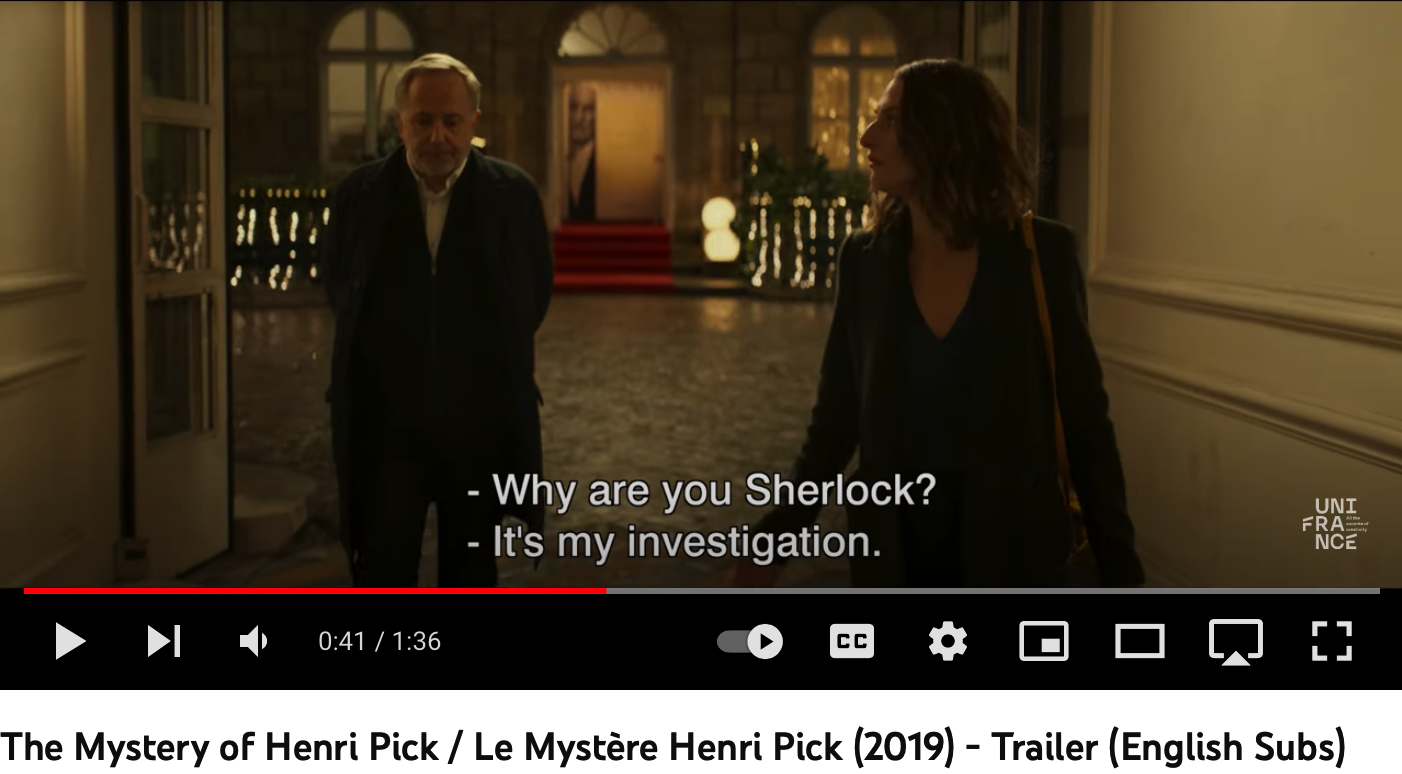

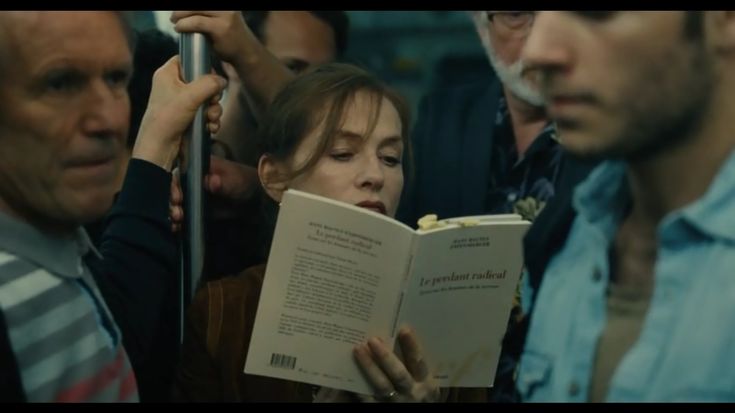

THE MYSTERY OF HENRI PICK - Trailer

DUE tomorrow, January 10 by 5:00 PM. Watch The Mystery of Henri Pick (dir. Rémi Bezançon, 2018). Write two Discussion Questions (50-200 words each) and three shots. Post Your DQs and THREE SHOTS on Canvas AND on this google document. Due tomorrow, Thursday, January 10 by 5:00 p.m. If you want to learn how to improve your discussion questions, I will be happy to meet with you during office hours or by appointment and show you.

January 9 General Questions for the Course: What Is Close Reading? What Is Closed Reading?

We will begin to address these questions by looking at one film and four literary works with analogues to close readers: the journalist; the cafe observer; the detective; the ghost-busting governess; the biographer; the Freudian analyst. Some of these analogues are related to forensics--evidence to establish the truth in a courtroom and reconstructing a crime scene. This legal method reading has its limits, as all analogies do (at some point, they break down). It assumes that truth is there to be found, discovered, and recovered. The truth is logical, rational, and a matter of consensus. In literature, the truth may be contradictory, impossible to ascertain, or to separate from irrational fantasies. What's in the text? What is not? These are not reducible to legal questions. Close reading is not exactly the opposite of closed reading, as we shall see.

Here is the an analogue of the journalist as close reader:

THE MYSTERY OF HENRI PICK - Trailer

January 11 Close(d) reading? The journalist (reading) as coroner; the library as tomb.

REQUIRED VIEWING:

The Mystery of Henri Pick (dir. Rémi Bezançon, 2018)

The film is in French with English subtitles. You will need to borrow a copy of the film on disc or rent it on a streaming service.

Recommended viewing:

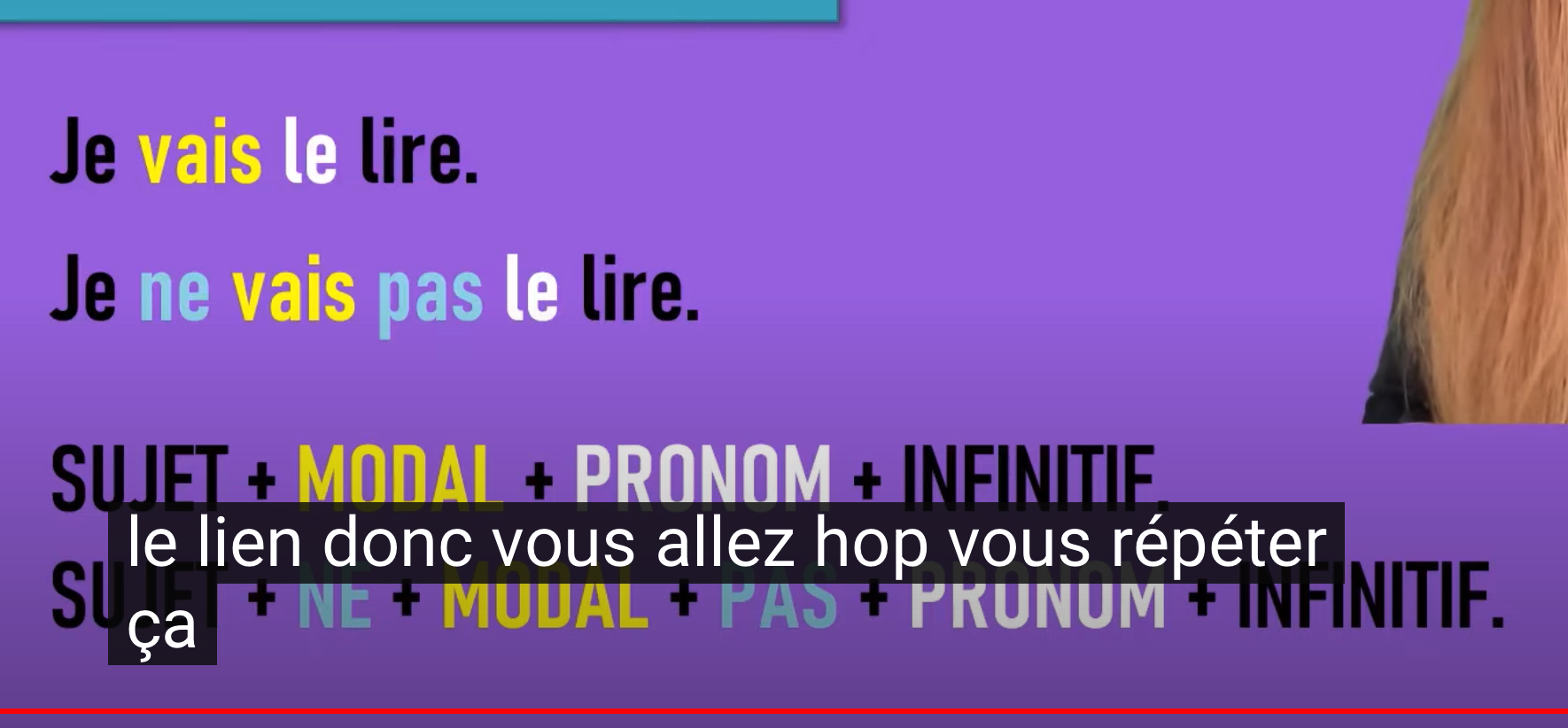

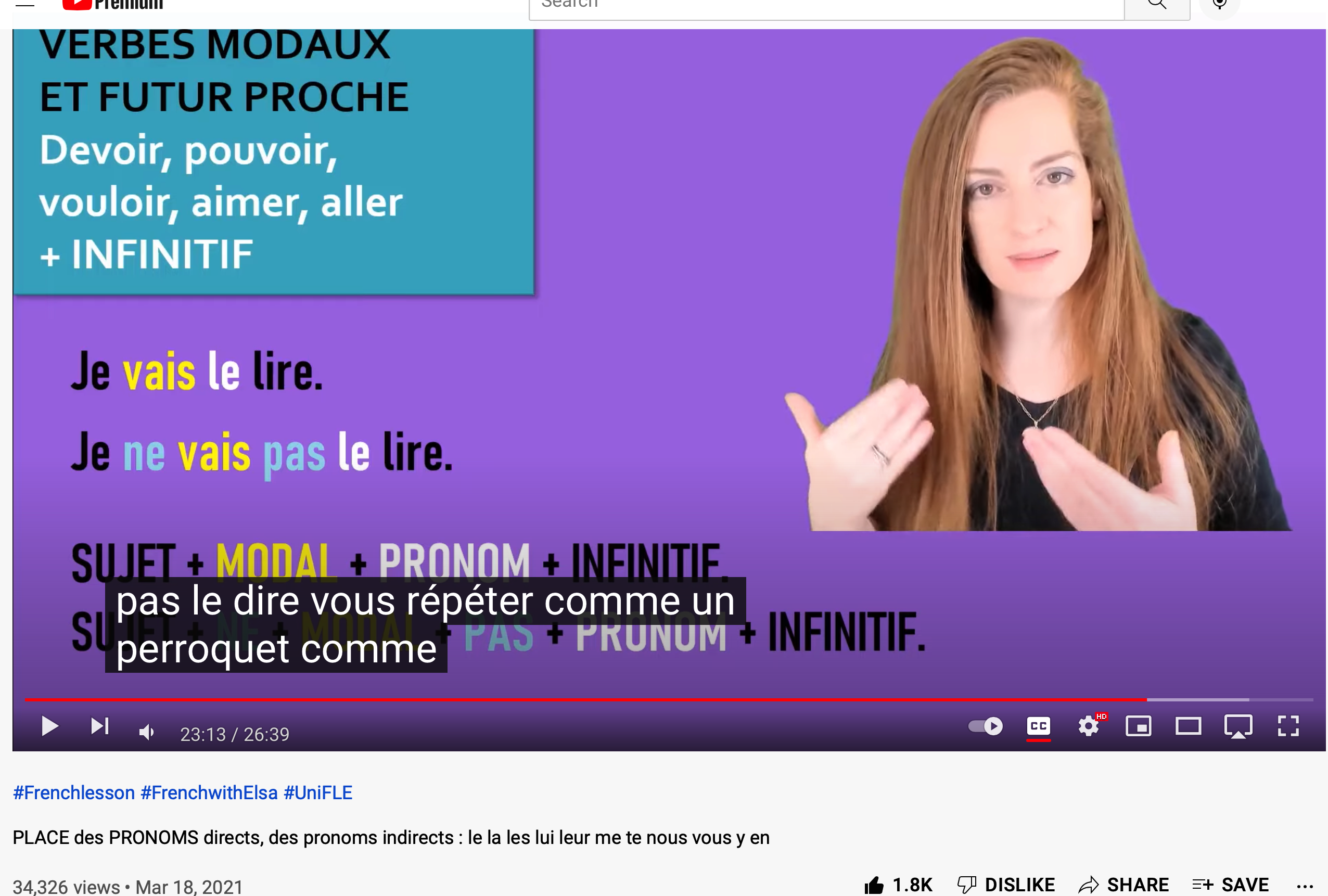

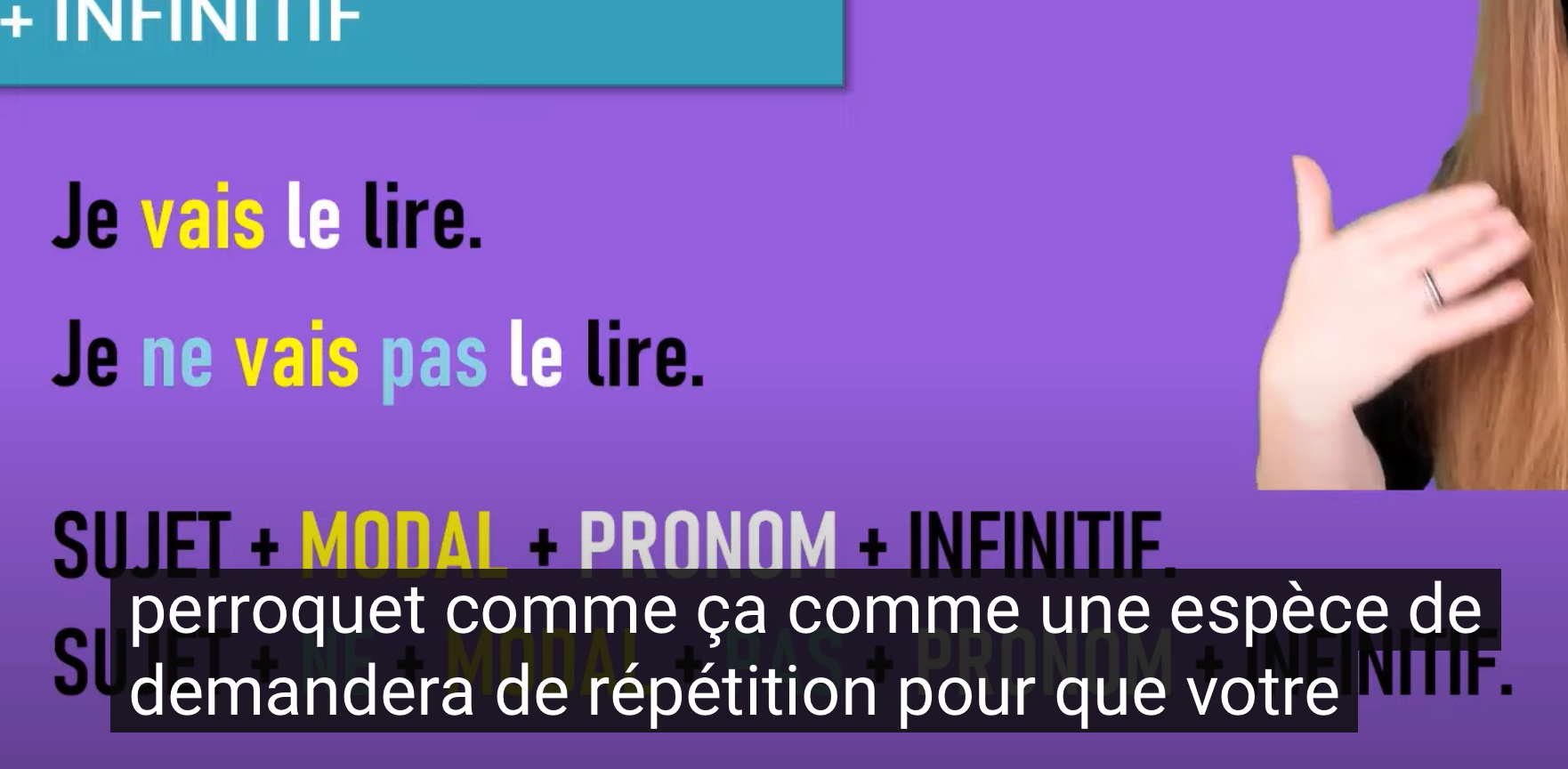

Watch online a French TV show (in French) of the kind represented in the film. Here is an example:

Découvrez la bibliothèque idéale: L'importance de la lecture dans la compréhension Feb 9, 2018

Recommend Reading:

Richard Brautigan, The Abortion: an historical romance 1966 (1972)

David Foenkinos, The Mystery of Henri Pick (read as an ebook)

Salon des Refusés (1863)

DUE January 12 by 5:00 PM: Read the poem "Aire and Angels" by John Donne several times. Write two Discussion Questions about the way it is written in a clear yet somewhat difficult manner and Three BIG WORDS. If you want to learn how to improve your discussion questions, I will be happy to meet with you during office hours or by appointment and show you.

January 13 John Donne, “Dark texts need notes.”

REQUIRED READING: Difficult Reading, or Donne in the Dark

John Donne, "Aire and Angels"

Recommended Reading:

John Donne, "The Good Morrow"

John Donne, "Lecture Upon a Shadow"

John Donne, "A Valediction of the Book"

(See also this 1962 Harvard Crimson review of Reuben A. Brower's edited collection, In Defense of Reading. Brower developed the idea of "slow reading.")

Margaret Edson, W;t (1995) has a scene with a terminally ill English professor noting a debate about a comma in one of Donne’s "Holy Sonnets." The main character mentions the name of a former student who published an ariticle on the Holy Sonnet. Here it is:

Richard Strier, "John Donne Awry and Squint: The "Holy Sonnets," 1608-1610"

Modern Philology Vol. 86, No. 4 (May, 1989), pp. 357-384

George Steiner, "On Difficulty" The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism Vol. 36, No. 3, Critical Interpretation (Spring, 1978), pp. 263-276

January 16

Holiday

To sign up to lead class, go to this google doc.

Create a google doc for your notes and share it with me by 5:00 p.m. the day before you are leading so I can add my thoughts. Make sure you give me permission to edit the document.

YOUR THIRD ASSIGNMENT, Due January 17 by 5:00 p.m.:

Here is an example of the detective as close reader:

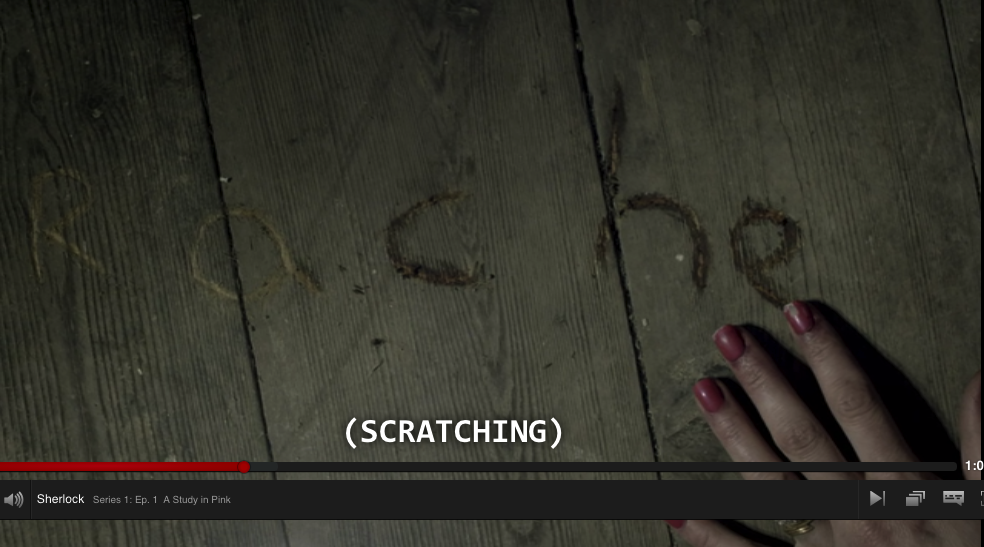

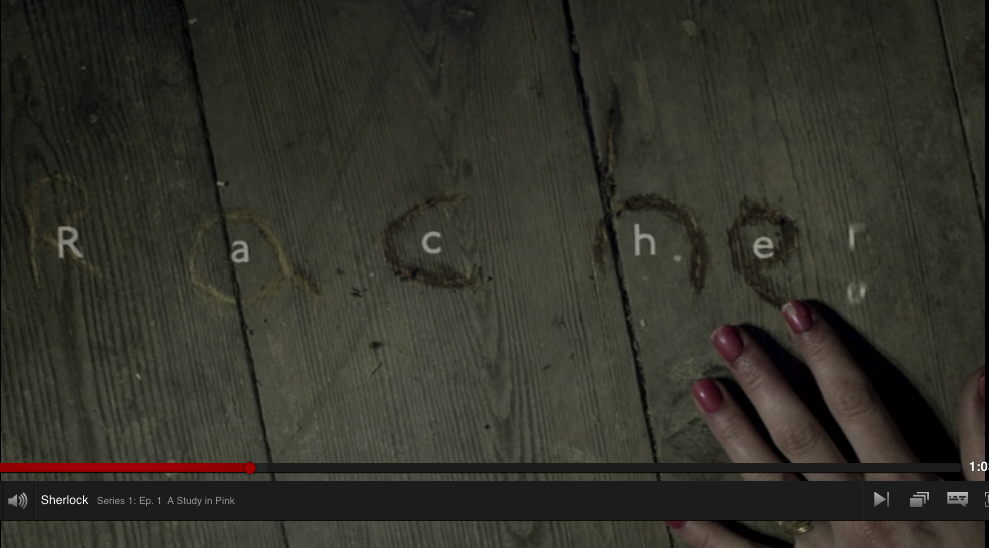

Sherlock "A Study in Pink" / (season 1, episode 1) 2010

The Crime Scene: Five letters--spelling "Rache"--have been scratched into a wooden floor by a murder victim. "Rache" is a German word meaning "revenge." But it turned out to be the first five letters of the proper name, "Rachel," the first name of the murderer.

Write two Discussion Questions and Three BIG WORDS on Edgar Allan Poe's "The Man of the Crowd." Post Your DQs etc BOTH on Canvas AND this google document here. If you want to know how to improve your discussion questions, I will be happy to meet with you during office hours or by appointment and show you.

DUE January 17 by 5:00 PM. Due January 17 by 5:00 p.m.

January 18 Closed Reading: Observation and Classification as Method or Madness? "Es läßt sich nicht lesen." (German for "it does not let itself be read.")

REQUIRED READING:

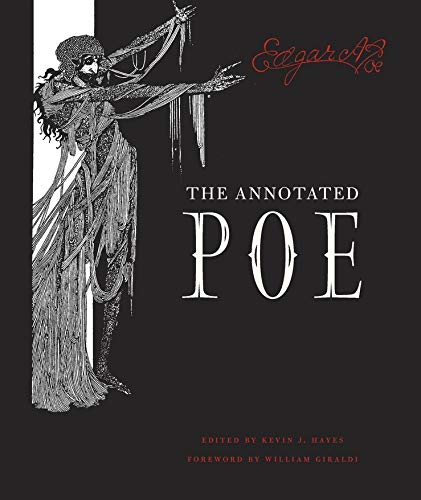

Edgar Allan Poe, "The Man of the Crowd" in The Annotated Poe, Ed. Kevin J. Hayes (Harvard UP, 2015 )

Recommended Reading:

Poe's Source? Edward Bulwer Lytton, Eugene Aram: A Tale (1832)

Friedrich August Moritz Retzsch Faust

Retzsch’s Outlines ( 1779-1857)

ISAAC DISRAELI, "RELIGIOUS NOUVELLETTES" in CURIOSITIES OF LITERATURE

“Hortulus Animæ cum Oratiunculis Aliquibus Superadditis” of Grünninger.

https://www.eapoe.org/works/mabbott/tom2t042.htm

https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/citylit/files/2015/07/poe_man_of_the_crowd.pdf

Carlo Ginzburg, “Clues: Morelli, Freud, and Sherlock Holmes,” in History Workshop, No. 9 (Spring, 1980), pp. 5-36.

Bran Nicol, "Reading and Not Reading 'The Man of the Crowd': Poe, the City, and the Gothic Text," Philological Quarterly, 91 (3) (Summer, 2012): 465-93.

Stephen Rachman, “Reading Cities: Devotional Seeing in the Nineteenth Century,” ALH 9 (Winter 1997), pp. 653- 675

Charles Dickens (source for Poe's Man of the Crowd), "The Streets—Morning, The Streets—Night, Shops and their Tenants, Meditations in Monmouth-Street, and Gin-Shops," in Sketches from Boz

Sketches by Boz "The Drunkard's Death"YOUR FOURTH ASSIGNMENT, Due January 19 by 5:00 p.m.

Read Edgar Allan Poe's "The Purloined Letter." Write two Discussion Questions and Three BIG WORDS. Post Your DQs etc. BOTH on Canvas AND this google document here.

Due Thursday, January 19 by 5:00 p.m.

I will no longer post due dates for Discussion Questions (DQs) and BIG WORDS. The work is due every Sunday and Tuesday by 5:00 p.m. unless otherwise noted.

January 20 The Eve of St. Agnes (we'll read Keats' poem on it later this semester)

The detective as close reader; hiding in plain sight; the frame as narrative device; is the reader outside the frame?

REQUIRED READING:

Edgar Allan Poe, "The Purloined Letter" in The Annotated Poe, Ed. Kevin J. Hayes (Harvard UP, 2015)

Recommended Readings:

The Mystery of Henri Pick

--Edgar Poe, "The Murders of the Rue Morgue"

The fate of reading and other essays by Hartman, Geoffrey H

Timestamp 1:23:02 The Mystery of Henri Pick (dir. Rémi Bezançon, 2018)

D.A. Greetham, "Textual Forensics"; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, "A Case of Identity" (1899) and "The Adventure of the Cardboard Box" (1893); Sigmund Freud, "The Moses of Michelangelo" (1914) Standard Edition, 13: 209-238. Digital "Exploded Manuscript" of Freud's essay."How DNA Changed the World of Forensics" NY Times, May 18, 2014

Walter Benjamin on Poe and Charles Baudelaire in "On Some Motifs in Baudelaire" and translating "À une passante" (pp. 223-24) and "Le Créspucle du soir"( pp. 324-27; p. 349n17)

Geoffrey H. Hartman, "Literature High and Low: The Case of the Mystery Story," The Fate of Reading and other Essays (1975), pp. 203-22

Experience: Description, Image, Memory

How Electricity Transformed Paris and Its Artists, from Manet to Degas

Joseph G. Kronick, "Edgar Allan Poe: The Error of Reading and the Reading of Error,"

"This change of weather had an odd effect upon the crowd, the whole of which was

at once put into new commotion, and overshadowed by a world of umbrellas."

Foreign Correspondent (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1940)

I will no longer post due dates for Discussion Questions (DQs) and BIG WORDS. They are due every Sunday and Tuesday by 5:00 p.m. unless otherwise noted.

January 23 The Governess as Close Reader (her story is being read aloud by a narrator to some friends) How Can You Tell What is True? Confessing and Narrating; two narrators; the story within a story.

REQUIRED READING:

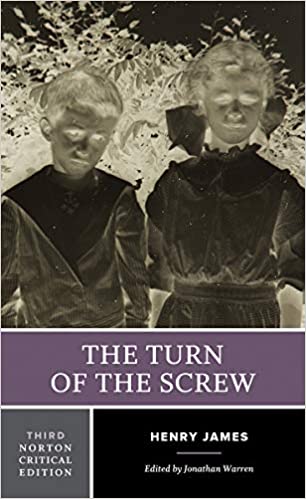

Henry James, The Turn of the Screw, Prologue and Chapters 1-VII (including chapter VII)

I recommend all of the editions below. Any one of them will do, though Peter G. Beidler's edition is the only edition to include both the Collier Weekly magazine version and the revised version in James' New York edition. Beidler is also the only editor to explore James' revisions exhaustively and make a persuasive case in his introduction and at greater length in his book The Collier's Weekly Version of The Turn of the Screw that they are significant. He is the best closer reader.

Henry James, The Turn of the Screw: A Case Study in Contemporary Criticism (Bedford/St. Martin's) Peter G. Beidler (Ed.)

Henry James, The Turn of the Screw and Other Ghost Stories (Penguin) Philip Horne (Ed.)

Henry James, The Turn of the Screw and Other Stories (Oxford World's Classics) T. J. Lustig (Ed.)

Henry James, The Turn of the Screw (Norton Critical Editions) Jonathan Warren (Ed.)

Recommended Reading:

To see what’s really going on, it helps to get close. NY Times series

"The 'frame' shows us through its incompleteness that there is no easy recourse to the author, whether implied or real, just as for the governess herself there is to be no recourse to the master, her employer."

--William R. Goetz, "The 'Frame' of The Turn of the Screw: Framing the Reader," Studies in Short Fiction 18.1 (1981): 71-7; 73.

January 25

REQUIRED READING: How do you know when to stop (re)reading? Do you have to stop reading to keep your sanity? (Neil Herz, The End of the Line) The Truth on Trial: Narrative Framing (1)

Henry James, The Turn of the Screw, Chapter VIII-XIV (including Chapter XIV)

Recommended Reading:

The Publication History of James' Story (quoted from wikisource):

"The Turn of the Screw" in Collier's Weekly (January 27–April 16, 1898)

January 27

DISCUSSION

FIRST PAPER DUE Saturday, January 28, by 11:59 p.m. Email all papers for the course to me at [email protected].You may write on any one of the assigned texts we have discussed except for The Turn of the Screw. 500-700 words.

John Donne, "Aire and Angels," Ed. Theodore Redpath for notes and APPENDIX V

January 30 James as his own closer reader (and editor) Write one DQ on each reading.

REQUIRED READING:

1. Henry James, The Turn of the Screw, Chapter XV to the end of the story

2. The Preface to Vol. 12 of the New York Edition (1908)

February 1 Ghost writing? "The story will tell." The Freudian reader as ghostbuster; the Freudian Reader as Close Reader? How close should you read? Can you read too closely?

REQUIRED READING: Write one DQ on each reading.

1. Edmund Wilson, "The Ambiguity of Henry James," (just read pages 89 through 95) first published in The Triple Thinkers (1948); revised version of a longer article originally published in Hound and Horn, VII, 385-406 (April-June, I933-34), 385-406.

2. Robert B. Heilman, "The Freudian Reading of The Turn of the Screw," Modern Language Notes Vol. 62 November, 1947, pp. 433-445.

Recommended:

Robert B. Heilman, "The Turn of the Screw as Poem," University of Kansas City Review 14 (1948): 277–89.

Harold C. Goddard, "A Pre-Freudian Reading of The Turn of the Screw," Nineteenth-Century Fiction 12 (1957): 1–36.

February 3

DISCUSSION (no required reading)

John Donne, "Aire and Angels" commentary and APPENDIX V, Ed. T Redpath

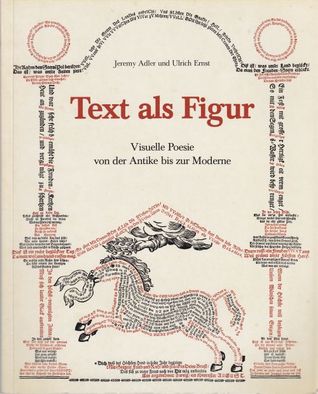

The literary page layout--Stéphane Mallarmé, "Un coup de Des jamais n'abolira le hasard"--white background becomes noticed as space, metaphorically becomes blank space.

Comparative (non)Reading (You may of course ignore the French original and read the English translation.)

Stéphane Mallarmé, "Un Coup de Des n'abolira le hasard" / "A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance," ed. and trans. A. M. Blackmore, Elizabeth McCombie, in French and English. 1897 and 1914 versions here--"a swift reading."

See Also / Further Reading

The Manuscript of Mallarmé's poem.

Caroline Bergvall & Nick Thurston, The Die Is Cast (2009). Only the last word of the translated title of the poem appears on the front cover, and the book is bound with one staple, just to the left of "CAST." Unfortunately, you can't see the staple in the digitzed image below.

Robert Walser, Microscripts

February 6 Is there a way out of reading? Is reading always open? Is is there always another way you have to turn the screw? Is the close reader sane or insane? Is the close reader a misreader? How would you know?

REQUIRED READINGS Write on DQ on each set of readings:

Shoshana Felman, "Turning the Screw of Interpretation," Yale French Studies No. 55 / 56, Literature and Psychoanalysis. The Question of Reading: Otherwise (1977), pp. 94-207.

1. Write your first DQ on these sections of Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation,":

I. An Uncanny Reading Effect," "II. What is a Freudian Reading?," and "IV. The Turns of the Story's Frame: A Theory of Narrative" pp. 94-102; 102-113; and 119-38.

2. Write your second DQ on these sections of Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation":

III.The Conflict of Interpretations: The Turns of the Debate, and X. A Ghost of a Master pp. 113-19 and pp. 203-07

NOTE: Felman's justly celebrated essay was retitled and republished as "Henry James: Madness and the Risk of Practice [Turning the Screw of Interpretation]," 141-250 in Writing and Madness (literature/philosophy/psychoanalysis) (1985); then republished with an "updated" new preface in 2003 after first appearing in the same book translated in French as La Folie et la chose littéraire (1978) but retitled as "Henry James: Folie et Interpretation," 237-346; then revised and republished again in a shorter version in a book edited by Felman, Literature and Psychoanalysis: The Question of Reading: Otherwise (1985), 94-207; and then abridged in excerpts and republished as "Turning the Screw of Interpretation," in Henry James, The Turn of the Screw Jonathan Warren, Ed. (Norton Critical Editions, 2021), pp. 215-30.

February 8

REQUIRED READING:

Write on DQ on each set of readings:

1. Write your first DQ on this section of Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation":

"V. The Scene of Writing: Purloined Letters" in Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation," pp. 138-48

2. Write your second DQ on this section of Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation":

VI. The Scene of Reading: The Surrender of the Name," in Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation," pp. 149-69

February 10

DISCUSSION

Recommended Readings:

Not saving or damning Felman's text:

Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, Felman

Felman Freud, "The 'Uncanny'".pdf

Freud, S. (1910) 'Wild' Psycho-Analysis. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 11:219-228.

Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams 3rd edition

A Casebook on Henry James's "The Turn of the Screw," ed. Gerald Willen, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1969, 2nd edition

Sigmund Freud, Delusion and Dream An Interpretation in the Light of Psychoanalysis of Gradiva, Part I

"Let us pause for a moment at this journey, planned for such remarkably uncogent reasons, and take a closer look at our hero's personality and behaviour."

Carlo Ginzburg, “Clues: Morelli, Freud, and Sherlock Holmes,” in History Workshop, No. 9 (Spring, 1980), pp. 5-36.

Sigmund Freud (1901) A. A. Brill translation Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1914)

REQUIRED READINGS:

VII. A Child is Killed in Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation," pp. 161-77

VIII. Meaning and Madness: the Turn of the Screw, in Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation," pp. 177-84

IX. The Madness of Interpretation: Literature and Psychoanalysis in Shoshana Felman's "Turning the Screw of Interpretation," p.185-204

February 15

REQUIRED VIEWING: The Fate of Reading

Things to Come (L'Avenir) dir. Mia Hansen-Løv, 2016

February 17

DISCUSSION

I. A. (Ivor Armstrong), Richards; Reuben Arthur Brower; Helen Hennessy Vendler, ed. I. A. Richards; Essays in his Honor (1973)

Raymond Queneau, Exercice de Style 1947 1963

February 20

REQUIRED READINGS:

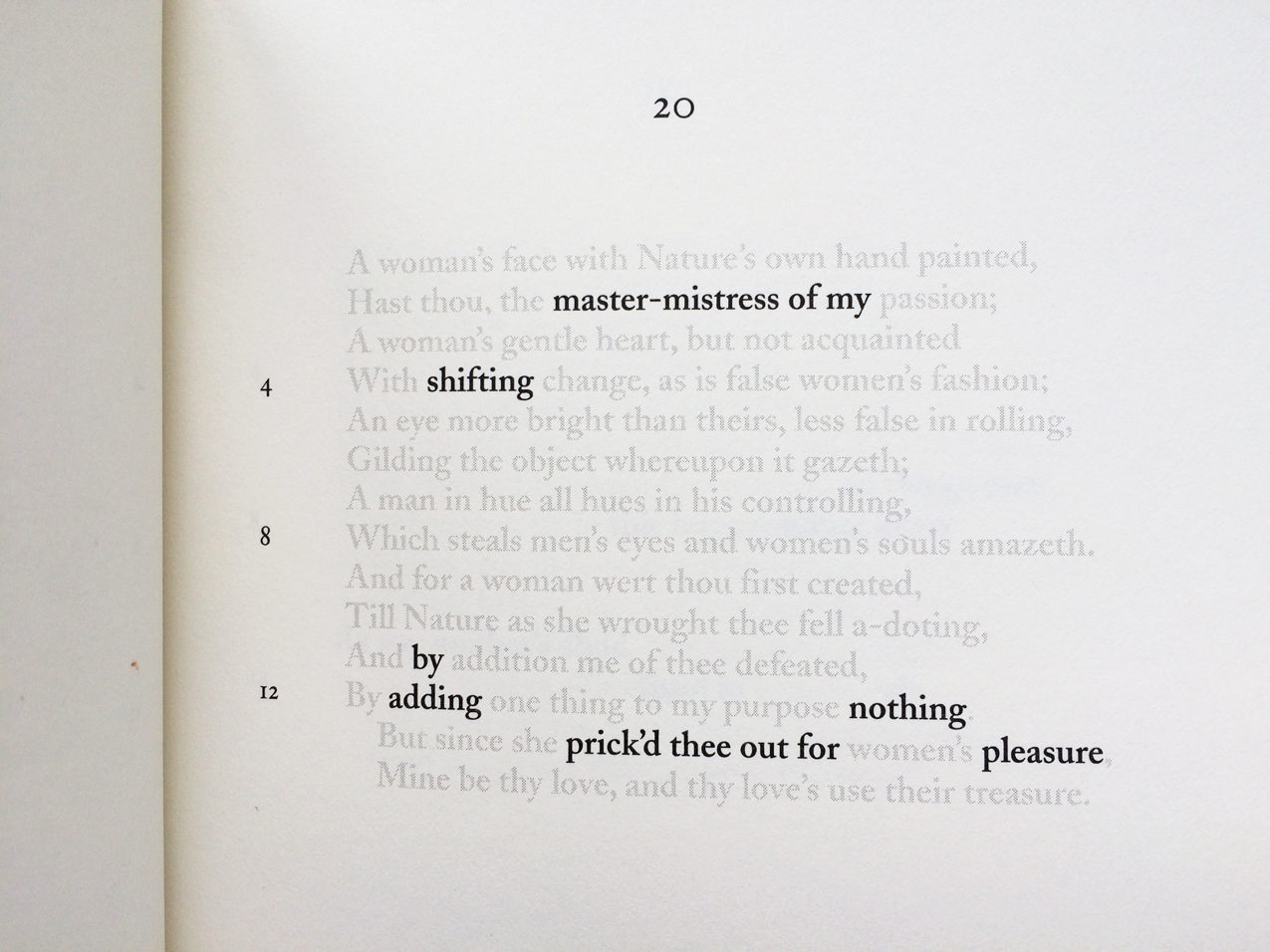

1. William Shakespeare, "Sonnet 93" and "Sonnet 94" with commentary on "Sonnet 93" and "Sonnet 94"

in Stephen Booth, Ed. Shakespeares Sonnets (Yale UP, 1977)

Recommended Reading:

Susan J. Wolfson, "Reading Intensity: Sonnet 12"

Helen Vendler, ed. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets (Harvard UP, 1997)

John Crowe Ransom," Shakespeare at Sonnets," The Southern Review (Winter 1938), pp. 531-96.

Stephen Booth, Essay on Shakespeare's Sonnets (Harvard UP), pp. 26–8.

February 22 The Critic as Close Reader

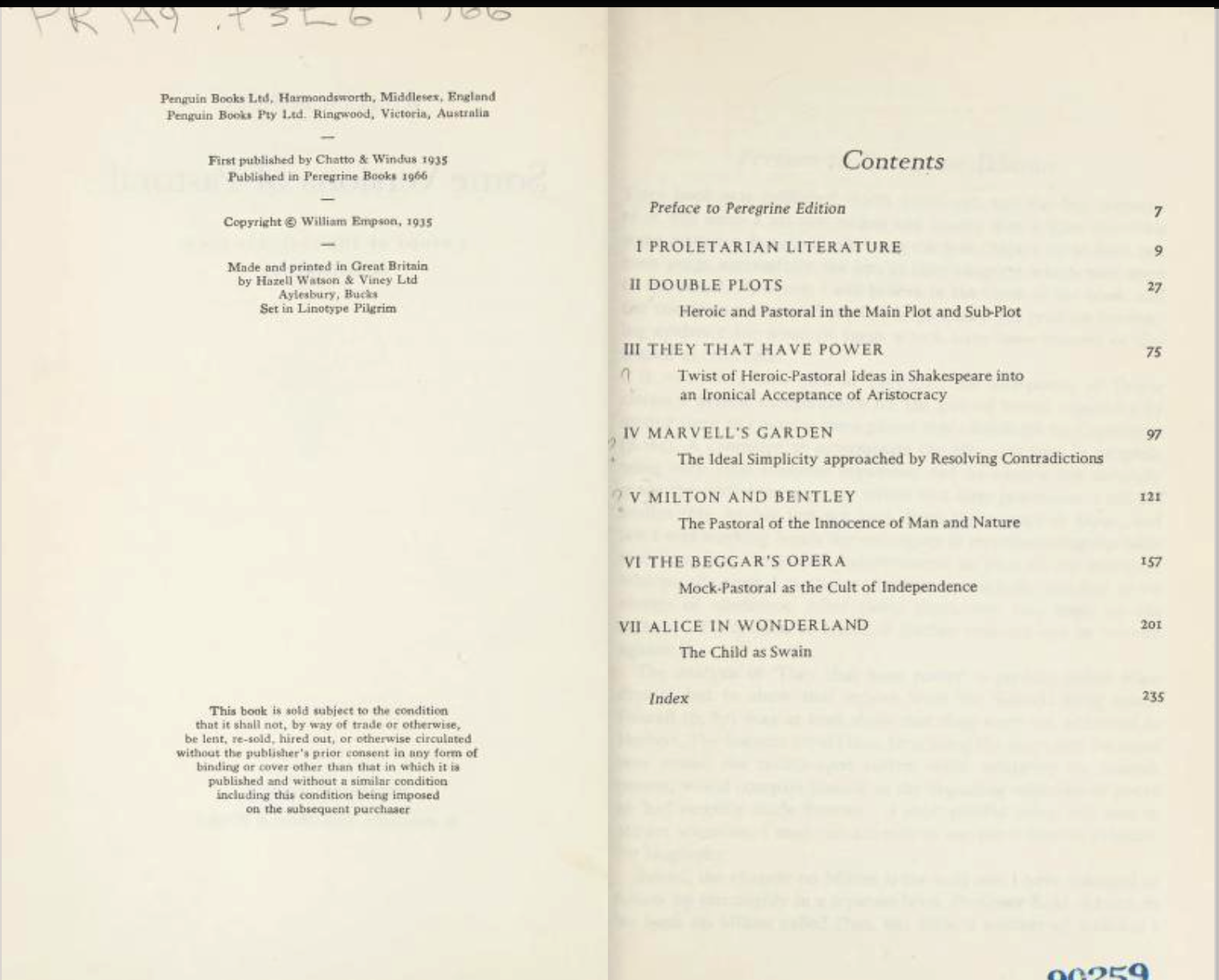

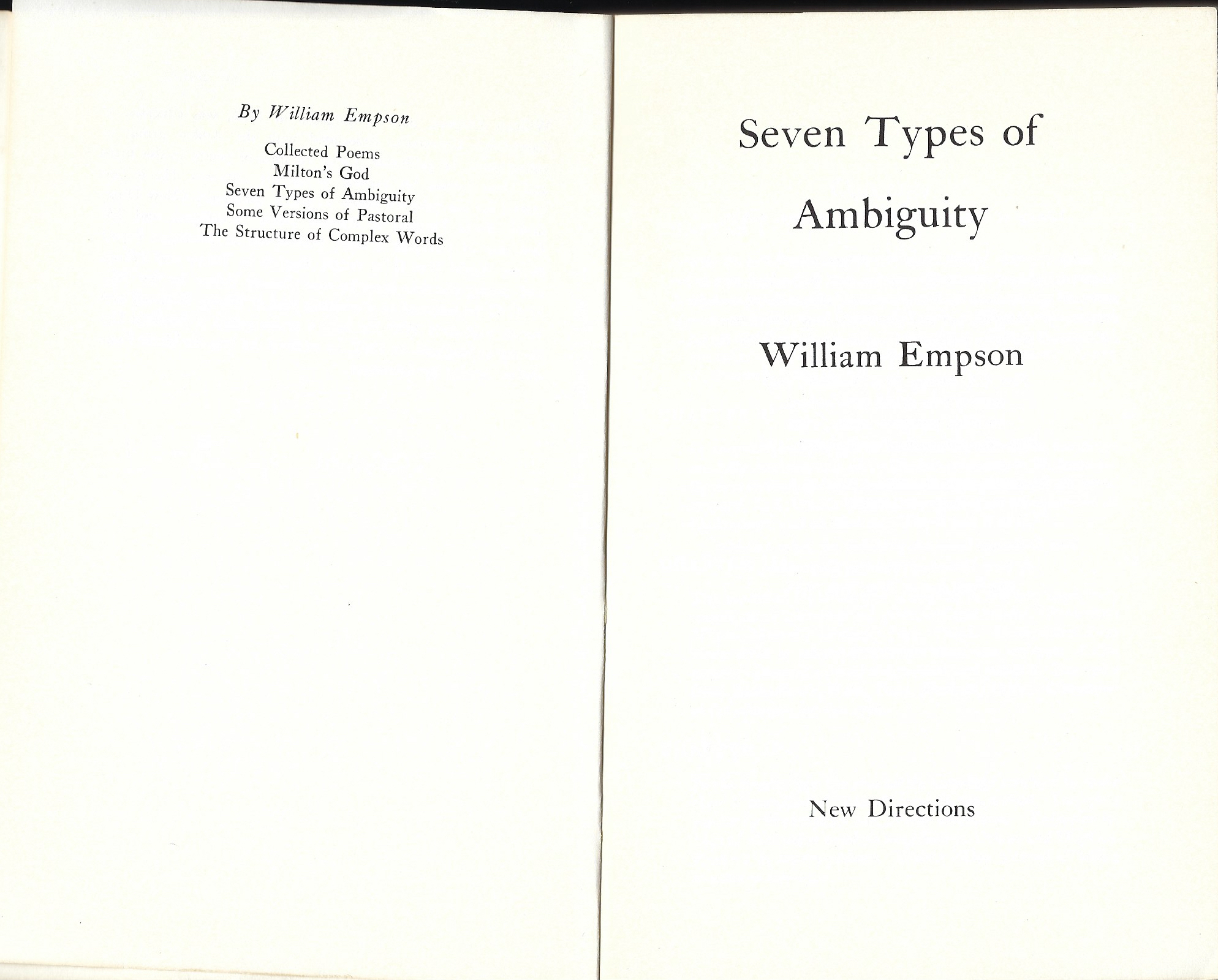

2. William Empson, "They That Have Power," in Some Versions of Pastoral, pp. 75-96

February 24

DISCUSSION

Jen Bervin, Nets (website) and Jen Bevins, Nets (scans of some pages in the book)

Double_Room/issue_five Jen_Bervin

February 27

REQUIRED READING:

1. Stephen Booth, "The Progress of Sonnet 94," in Essay on Shakespeare's Sonnets (1968)

2. William Empson, 7 Types of Ambiguity, on Shakespeare's Sonnets

RECOMMENDED LISTENING:

Sonnet 75 (“So are you to my thoughts as food to life”)

Read Aloud by Patrick Stewart

Sonnet 94 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart) | 2020.07.27

Sonnet 93 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart) | 2020.07.26

95

Sonnet 32 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart) | 2020.04.19

Sonnet 13 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart)

Sonnet 31 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart) | 2020.04.18

Sonnet 74 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart)

Sonnet 81 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Ian McKellen) | 2020.07.13

Sonnet 81 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Simon Russell Beale)

Sonnet 81 by William Shakespeare (read by Al Pacino)

Sonnet 82 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart)

Sonnet 16 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart)

Sonnet 58 by William Shakespeare - Read by John Gielgud

Recommended Reading:

Shakespeare's Sonnets, Ed. Ingram and Redpath

Helen Vendler, ed. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets(Harvard UP, 1997)

March 1

REQUIRED READINGS (Write two DQs):

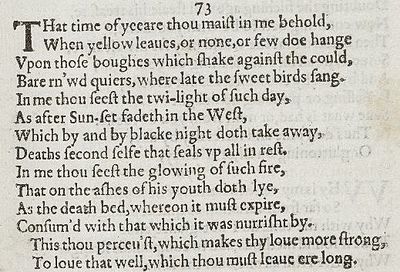

1. Willian Empson, 7 Types of Ambiguity (1947), second edition, pp. 2-3; 226-233. There are two digital facsimiles on archive.org: first and second. Readers left their marks in the sourced printed copies. There is also a diplomatic transcription here. You can cut and paste from it.

2. William Shakespeare, "Sonnet 73" in Stephen Booth, Ed. Shakespeares Sonnets, preface, facing page facsimiles and modernized sonnets, and commentary (Yale UP, 1977). (Just read the poem. You don't need to read the commentary.)

Sonnet 73 by William Shakespeare (read by Sir Patrick Stewart)

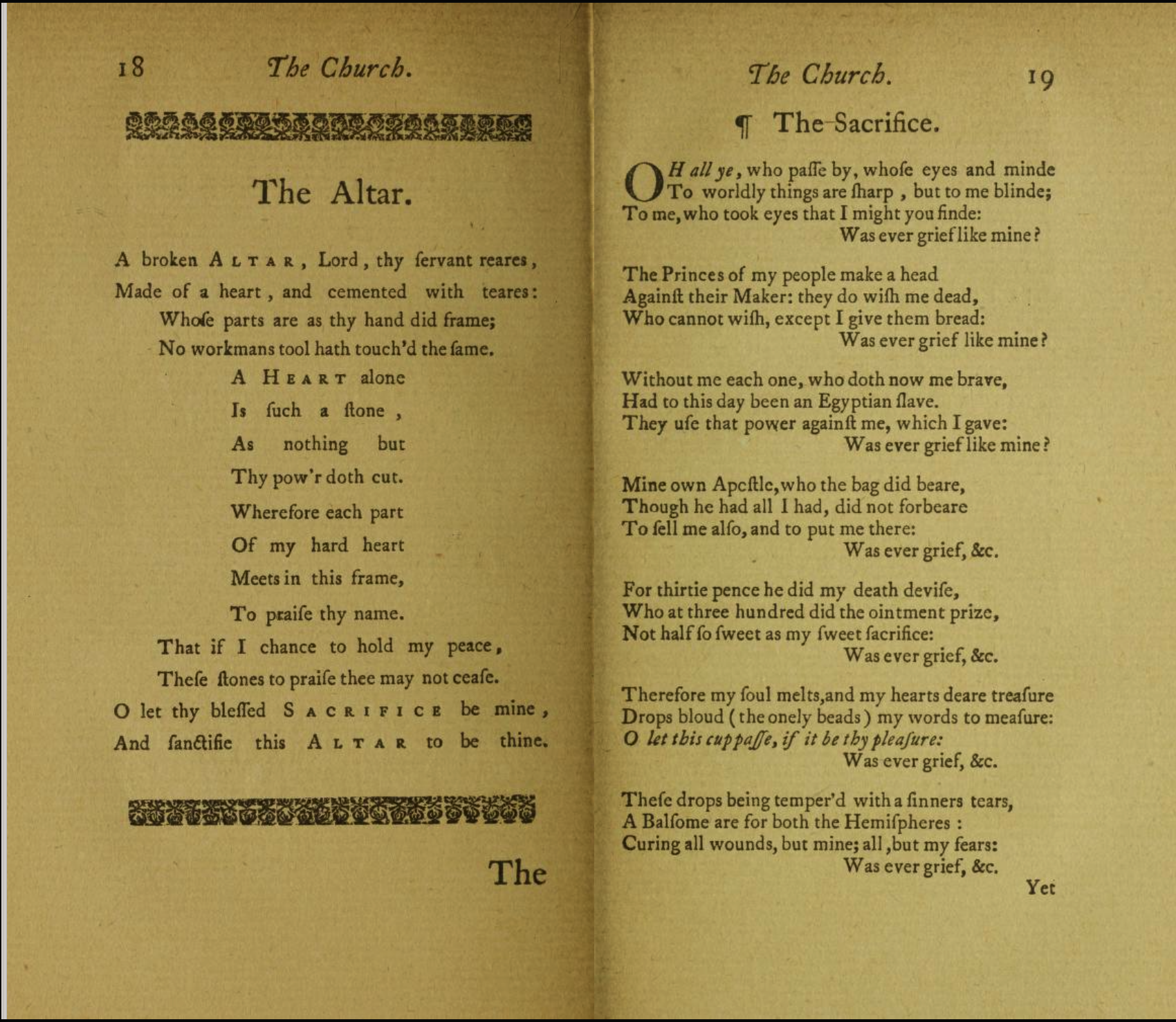

2b. George Herbert's "The Sacrifice" (1633; reprinted 1876), pp. 19-26. (Here is a later edition with footnotes--[1899].)

"Was ever grief, &."

RECOMMENDED READING:

"warning" "The first and only previous edition of this book was pub-

lished sixteen years ago. Till it went out of print, at about

the beginning of the war, it had a steady sale though a small

one; and in preparing a second edition the wishes of the buyers

ought to be considered. Many of them will be ordering a

group of books on this kind of topic, for a library, compiled

from bibliographies; some of them maybe only put the book

on their list as an awful warning against taking verbal analysis

too far.

because they have to be borne in mind in any case.)

--William Empson, Seven Types of Ambiguityp. 241

The Temple Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations. By Mr. George Herbert.

At the end . . . (I'll translate it in class.)

fourchue--forked; "Il etait une fois" means "once upon a time)

Frank Kermode, "Disgusting" Vol. 28 No. 22 · 16 November 2006

March 3

DISCUSSION

Recommended:

P. D. Eastman, Go, Dog. Go! (1961)

Stephen Booth, “Go, Dog. Go! A Map of the Beautiful,” in Reading What's There Essays on Shakespeare in Honor of Stephen Booth Ed. MICHAEL J. COLLINS (University of Delaware Press, 2014)

REQUIRED READING: (Write one DQ on each reading.)

1. William Wordsworth, "The Lucy Poems" (1798-1801)

2. J. Hillis Miller versus Meyer Abrams on Wordsworth's "A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal"

Recommended Reading:

Adam Kirsch, "Strange Fits of Passion: Wordsworth’s Revolution," in The New Yorker, November 27, 2005.

Frederick Wilse Bateson, English Poetry: A Critical Introduction (1950), pp. 29-30

Cleanth Brooks, "Irony and "Ironic" Poetry," College English, Feb., 1948, Vol. 9, No. 5 (Feb., 1948), pp. 231-237

E. D. Hirsch, Jr., "Objective Interpretation," PMLA, Vol. 75, No. 4 (Sep., 1960), pp. 463-479

Steven Knapp; Walter Benn Michaels,"Against Theory," Critical Inquiry, Vol. 8, No. 4. (Summer, 1982), pp. 723-742.

REQUIRED READING

I. A. Richards, Practical Criticism (1929) "Preface; Intoduction; Part Two: Documentation, pp. vii-29; Appendix B, C, and D, pp. 347-57.

Recommended:

Life's more than breath and the quick round of blood;

It is a great spirit and a busy heart.

The coward and the small in soul scarce do live.

One generous feeling--one great thought--one deed

Of good, ere night, would make life longer seem

Than if each year might number a thousand days,

Spent as is this by nations of mankind.

We live in deeds, not years; in thoughts, not breaths;

In feelings, not in figures on a dial.

We should count time by heart-throbs. He most lives

Who thinks most--feels the noblest--acts the best.

Life's but a means unto an end--that end

Beginning, mean, and end to all things--God.

March 10

DISCUSSION

See Also / Further Reading:

Sharmila Cohen and Paul Legault, Ed. The Sonnets: Translating and Rewriting ShakespeareI. A. Richards, Mencius on the Mind: Experiments in Multiple Definition (1964)

In Brief Gatherings By Gill Partington May 10, 2019 IN THIS REVIEW CATCH-WORDS 148pp. Information as Material. Paperback, £14. Nicholas D. Nace

SECOND PAPER DUE March 11 by 11:59 p.m. READ THROUGH THIS WEBPAGE. READ ALL OF IT. CLOSELY. VERY CLOSELY. PLEASE NOTE: Now that you have learned from your mistakes in our discussion of your first paper, and now that you have practiced writing twice a week through your DQs, I fully expect you to be able to make an argument in your essay, write grammatical sentences, use words properly, and punctuate properly. Papers that have ungrammatical sentences, mispunctuate, or misuse words will get "D" grades. Be sure to give yourself time to revise and to proofread your paper carefully before you send it to me at [email protected]. I recommend reading your work aloud. It's a good way to see what you need to revise. You can also get help at the Writing Program. See also the Plain Style: A Guide to Written English. READ THROUGH THIS WEBPAGE. READ ALL OF IT. CLOSELY. VERY CLOSELY.

Email your second paper as a word docx to me at [email protected]

March 13 SPRING BREAK

March 15 SPRING BREAK

March 17 SPRING BREAK

March 20: Reading as an Academic: Your Cross-Reference to bear; Commentary as encryption / decryption.

Focus your DQs on the way Nabokov creates a fictional editor and first person narrator, Charles Kinbote, who is an academic and who gains possession ofa fictional manuscript of a poem written by his colleague, neighbor, and supposed close friend, John Shade, after Shade is murdered. The (unfinished?) poem is written on the author's index cards. Kinbote has the poem published his own foreword and an extensive, deeply learned but at times absurd (the King of Zembla and Gradus subplot) line-by-line critical commentary on it as well as an index by Kinbote.

Required Reading:

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire, pp. 11-110; the reading ends with "and while pacing about and pondering his." You can read the novel online here. (One hour loan) Here. And Here. An audiobook is here: Pale Fire Vladimir Nabokov 9 Hours Full Audiobook.

The Vintage edition of Pale Fire is also on Kindle. And there is a sort of hypertext edition on line (The Vintage edition is the source text): Pale Fire A Poem in Four Cantos

The Reason for this new html version

Nabokov took the title of his novel from Shakespeare's tragedy Timon of Athens.

Recommended Reading for Ryhming Couplets:

Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man: Epistle I

Recommended Readings:

Pale Fire Canto 4 Commentary Project.

Pale Fire: A Poem in Four Cantos by John Shade 2011)

Dmitri Nabokov, The Original of Laura

Yuri Leving, ed. Shades of Laura: Vladimir Nabokov's Last Novel, The Original of Laura Oct 28, 2013

“Pale Fire” without Charles Kinbote | BLT

"This new scholarship may not only have filled in the mystery of the book’s first owner and annotator; it may also show the full degree to which Milton engaged with Shakespeare, and give Milton scholars 'a new and significant field of reference' for reading his work."

Claire M.L. Bourne, "Vide Supplementum: Early Modern Collation as Play-Reading in the First Folio"

March 22

REQUIRED READING

Required Reading:

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire, pages 110-210, ends with "He knew she had just come across a telltale object--a"

Recommended Reading:

Eugene Onegin - Alexander Pushkin audiobook Trans. James E. Falen

Nabokov’s Copy of Eugene Onegin:

Edmund Wilson, "The Strange Case of Pushkin and Nabokov," The New York Review of Books

READING WITH THE INDEX

Nabokov's translation and preface (4 Volumes)

March 24 The Idea of an Ideal Text (Is there a material "text?" or even a "book?" or "page"?)

DISCUSSION

Recommended Reading:

DENNIS DUNCAN, "Indexing Fictions" in Index, A History of: A Bookish Adventure from Medieval Manuscripts to the Digital Age (2022), pp. 171-202.

See also "Introduction," pp. 1-18 and "Point of Order," pp. 19-48

Dennis Duncan (Editor), Adam Smyth (Editor) Book Parts (2019)

J.G. Ballard, "The Index," The Paris Review, vol 118, (Northern) Spring, 1991. It is copyright © the Estate of the Late J.G. Ballard, 1977, 1991.

Jane Austen, Emma, An Annotated Edition. Ed. Bharat Tandon (Belknap Press, 2012).

Which books does Emma read? See p. 58n.13.

Reading made easy: Leah Price, The Anthology and Rise of the Novel (quotable sound bites).

March 27:

REQUIRED READING:

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire, pp. 211-315 (Finish reading the novel.)

Recommended Reading:

T. S. Eliot, FOUR QUARTETS (1943)

T. S. Eliot reading his 'Four Quartets' (1947)

Alec Guinness reads Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot

Edmund Wilson, "The Fruits of the MLA: I. 'Their Wedding Journey'” NYRB September 26, 1968

March 29 The Literary Cross-Reference

Why does Gérard Genette hate Pale Fire so much? The reader as literary theorist; functionalist purpose of the paratext (it remains invisible) versus literary derailing of the paratext through self-consciousness (the writer calls attention to the paratext and its dysfunction).

Required Reading:

Genette's "Introduction, Conclusion, Introduction and Conclusion (pp. 1-15; 405-10) and the discussion of Pale Fire in Paratexts (p. 10; p. 84; p. 289; p. 289n.49 is on Lolita; 323; 341-43) and the conclusion.

Gérard Genette, Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation,

March 31 The spatial metaphors for the structure of Herbert's The Temple run counter to Genette's use of "vestibule" as a metaphor for the paratext. Herbert titles the introductory poems as parts of the church. A spatial metaphor of architecture for the paratext becomes architextual. In Genette’s case, the paratext is supposed to be what you don’t (have to) read. Herbert synthesizes literary effects (titles of poems) and their architexture (ordered as if they were a blueprint or tour guide) with the pragmatic function titles have. Thesubject of Herbert's work of literature is nearly identical to its text and paratexts. Genette thinks that literary effects get in the way of the paratext's primary, pragmatic function of helping the reader understand the text or orient themselves int it . Seuils, a metaphor used as the title of Genette's book betrays a certain ambivalence in Genette both about the literariness of literary theory and about the literariness of his own very witty style. Seuils is a metaphor that opens onto every peritext and epitext. It is also a pun on the name of Genette's prestigious publisher, Seuils.

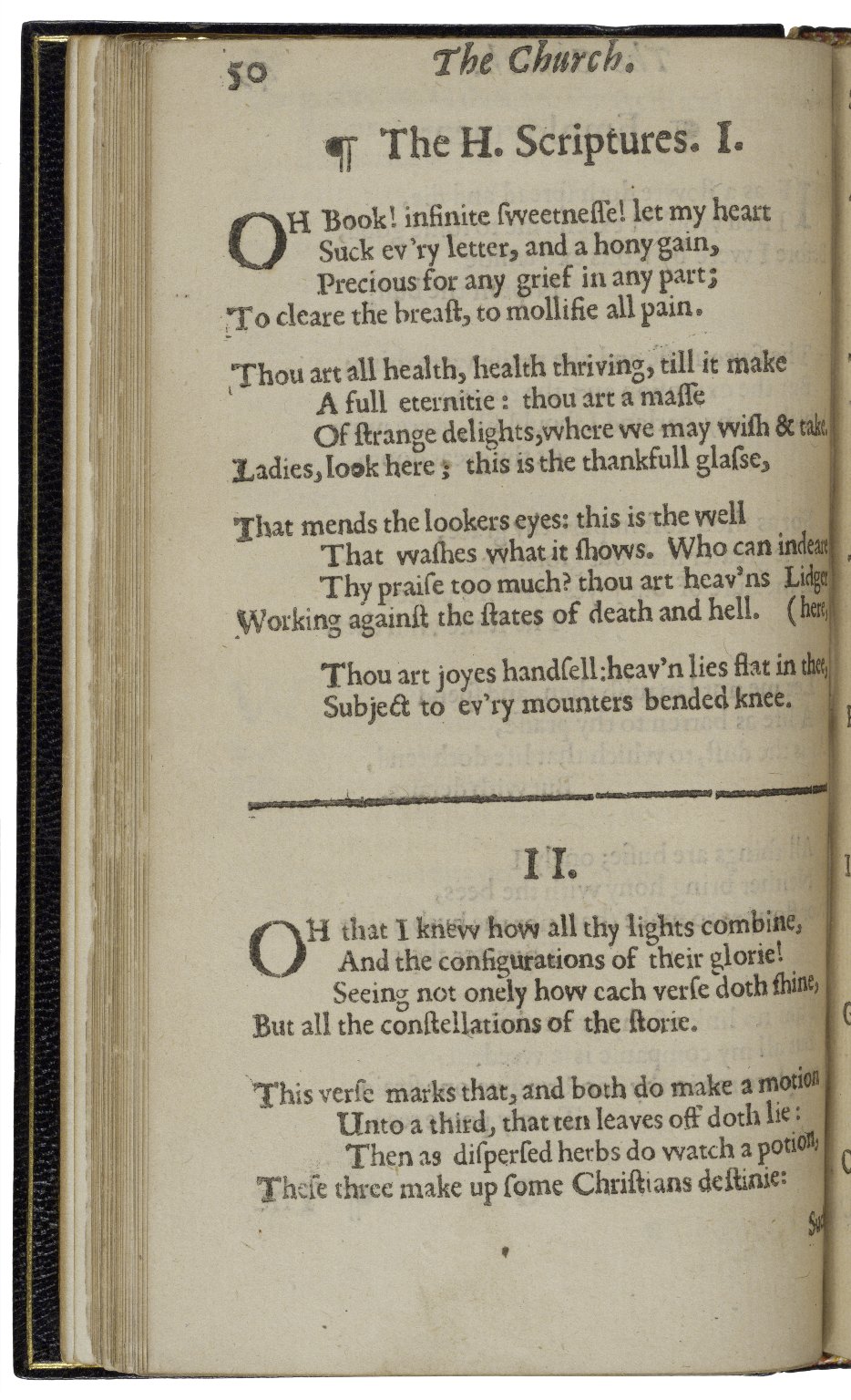

The Reader as Devotional Poet: "See Also" as a dazzling metaphor for discontinuous reading (Holy Sonnets II)

Recommended Reading: A Brief Biography of Herbert

Required Reading:

1. NICHOLAS D. NACE, "On Not Choking in Herbert's "The Collar," in Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 55, No. 1, The English Renaissance (WINTER 2015), pp. 73-94.

2. "The Altar"; "The Collar"; "The Bag"; "The Flower"; "Miserie": "Jordan (I) and (II)"; "The Pearl"; "Holy Scriptures (I) and (II); "The Holdfast"; "The Sepluchre"; "Easter Wings"; "Redemption Affliction (I)"; "Prayer (I)";--a sonnet without a transitive verb! "Church Monuments"; (where he sounds most like Donne); "Vertue"; "Submission"; "Dialogue"; "Sinnes Round"; "Paradise"; "The Forerunner"; "A True Hymne Bittersweet," in The Temple Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations. By Mr. George Herbert. 1633 Printed by Ferrar, Nicholas.

Here: The facsimile of each page and a diplomatic transcription of each poem.

(Holy Scriptures) I I.

OH that I knew how all thy lights combine,

And the configurations of their glorie!

Seeing not onely how each verse doth shine,

But all the constellations of the storie.

This verse marks that, and both do make a motion

Unto a third, that ten leaves off doth lie:

Then as dispersed herbs do watch a potion,

These three make up some Christians destinie:

Such are thy secrets, which my life makes good,

And comments on thee: for in ev’ry thing

Thy words do finde me out, & parallels bring,

And in another make me understood.

Starres are poore books, & oftentimes do misse:

This book of starres lights to eternall blisse.

Recommended Reading:

Ran- dom Cloud, "FIAT fLUX," in Crisis in Editing: Texts of the English Renaissance

Herbert, George, 1593-1633.Outlandish proverbs, selected by Mr. G.H.

Critic as Ho(st)LY FoOl Either You Criss or You Cross (Out or Off)

GEORGE HERBERT, "LOVE (III)"

“The Real Presence of Absent Puns: George Herbert’s ‘Love (III),’” in Shakespeare Up Close: Reading Early Modern Texts, ed. Nicholas Nace, Russ McDonald, and Travis D. Williams (London: Arden Shakespeare, 2013), pp. 76-83.

Prayer and Power- George Herbert and Renaissance Courtship

“I should now get back to the value of unmade puns.”

--Stephen Booth, Shakespeare Sonnets (Yale UP, 1977) p. 195

REQUIRED READING:

John Keats, "Ode to a Nightingale"; "Ode on Melancholy"; "Ode to Psyche"; and "Ode on a Grecian Urn" (in manuscript)

Cleanth Brooks, "The Heresy of Paraphrase," in The Well-Wrought Urn.

William Empson, "Thy Darling in an Urn," The Sewanee Review Vol. 55, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 1947), pp. 691-697 (7 pages)

Cleanth Brooks, "Postscript" (pp. 697-699)

RECOMMENDED READING:

T.S. Eliot, "The Music of Poetry," in Poetry and the Poets, p. 30

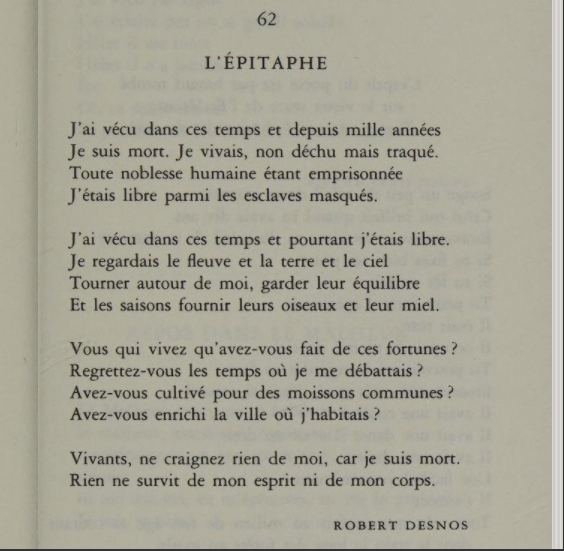

"déchu"--fallen; "traqué"--hunted; tracked down; "débattais"--struggled; "moissons"--harvest; crops

April 5 The Reader as Editor and Annotator

REQUIRED READING (one DQ on each poem):

John Keats, "The Eve of Saint Agnes" and "La Belle Dame Sans Merci" (also "Mercy" in a second version) read by Ben Whishaw

Recommended Reading:

The rough first draft of The Eve of St. Agnes (Harvard has published digitized facimiles of a huge number of Keats' manuscripts.)

A pdf of Leigh Hunt's preface and commentary on some of Keats' poems in The Indicator (1822)

On google books:

Leigh Hunt · The Indicator August 8, 1822

For "Old Romance," see

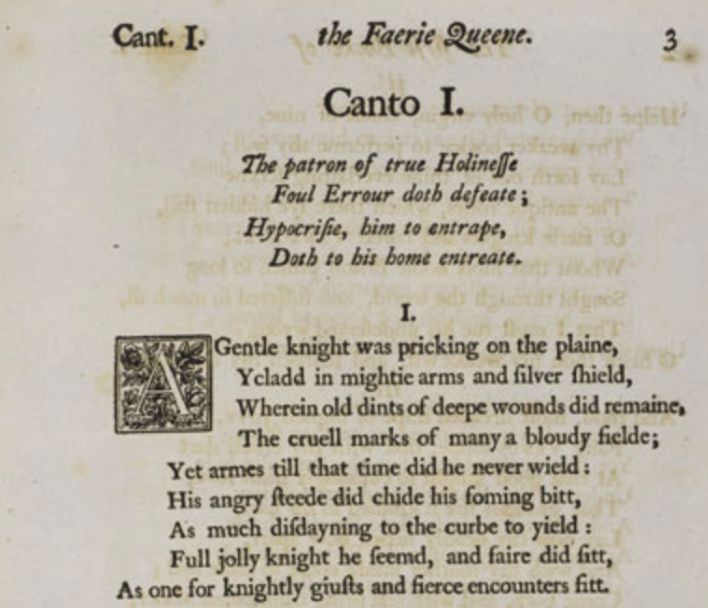

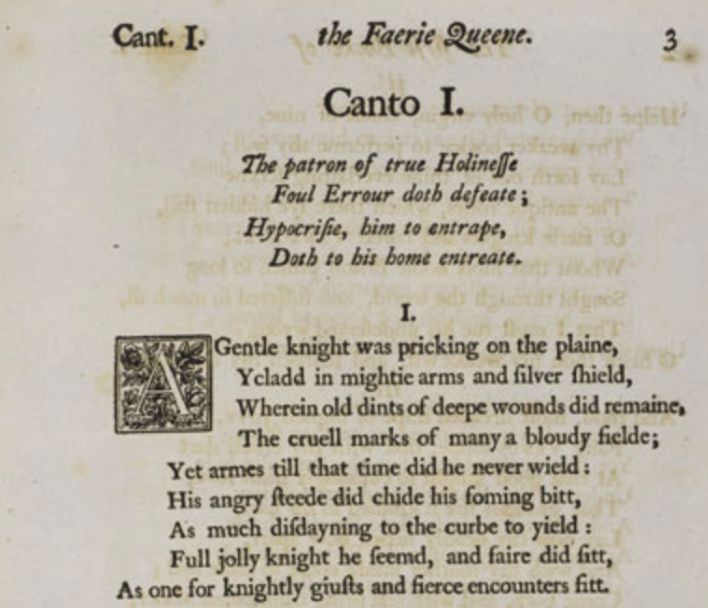

The Red Crosse Knight's dream of Una in Book I of Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene

DISCUSSION and Required Reading:

Susan Wolfson, A Greeting of the Spirit: Selected Poetry of John Keats with Commentaries, pp. 248-68.

REQUIRED READING:

1. William Wordsworth, Essays Upon Epitaphs (1810), pp. 642 and ff.

2. Paul De Man, "Autobiography as Defacement" MLN, Vol. 94, No. 5, Comparative Literature issue (Dec., 1979), pp. 919-930

April 12 The Critic as Smartie or Dummy / On Incomprehensibility

REQUIRED READING:

Paul De Man, "The Concept of Irony" and "unreadability" (Allegories of Reading)

April 14

Discussion

Let's fold these questions into one and ask a question about the potentially readable: "what is there to be read?"

Required Reading:

T.S. Eliot, The Wasteland (1922) online facsimile of the published version vs. the published text with marginal commentary with Eliot's notes vs. the published text without commentary or notes.

April 19 Author versus Art: Eliot and Céline

Required Reading:

William Empson, "Using Biography 'Eliot- My God man, there's bears on it.'"

Recommended:

Alice Kaplan, "The Master of Blame," The New York Review of Books (July 21, 2022)

Adam Gopnick, "A Newly Discovered Céline Novel Creates a Stir," The New Yorker, Jun 15, 2022

The Holberg Lecture 2016: Stephen Greenblatt: "Shakespeare's Life-making"

The Meanest Things Vladimir Nabokov Said About Other Writers

MUSING UPON THE KING’S WRECK: T. S. ELIOT’S THE WASTE LAND

IN VLADIMIR NABOKOV’S PALE FIRE

Valerie Eliot, ed. The Waste Land: A Facsimile & Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound (2020) pp. TBA

April 24

Required Reading:

Valerie Eliot, ed. The Waste Land: A Facsimile & Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound (2020) pp. TBA

April 26

THIRD PAPER DUE April 26, presented. [email protected]

YOUR THIRD AND FINAL. Presented in class the final class of the semester.

On the google document linked below, construct a table of contents for the commentary in Pale FIre creating running titles to desribe the note using five notes of your choice. You may cut and paste the notes from this website.You may consider your document an anthology of extracts. In 300 words, write a brief preface explaining the critical basis of your selection of extracts. Give the word counts for each note. And enter all of your BIG WORDS into the dictionary at the bottom of the google doc. Consult each other to make sure you don't select the same notes.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Tl6QdgPQsLloY8gk8UA4P_0UGk23DgBdkHKRp8JUP8s/edit

Your can use these tables of contents as a model. Here is Empson's:

Or consider this more playful use of chapter titles and subtitles:

See what the editor of this anthology of extracts did in

THE BEAUTIES OF STERNE: INCLUDING ALL HIS PATHETIC TALES, AND MOST DISTINGUISHED OBSERVATIONS ON LIFE. SELECTED FOR THE HEART OF SENSIBILITY.

See the strange summaries editors put at the end of each volume of Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time.

NOTHING BELOW IS REQUIRED FOR THIS COURSE. YOU MAY IGNORE IT ALL.

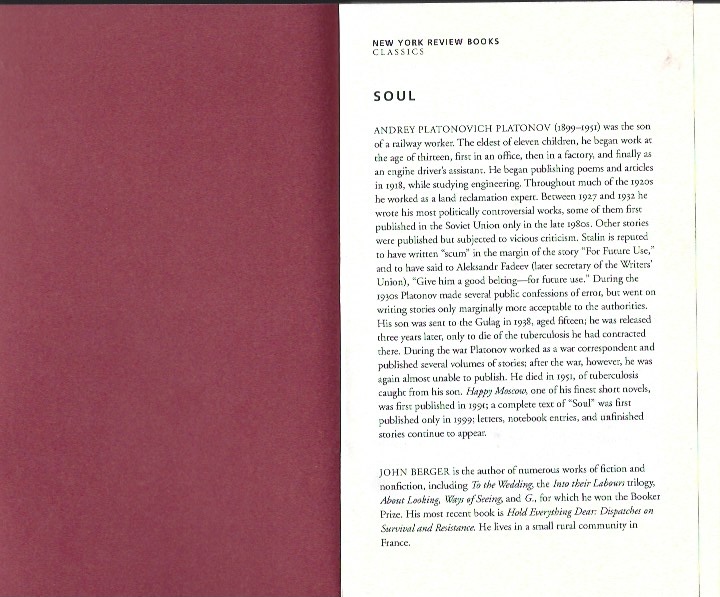

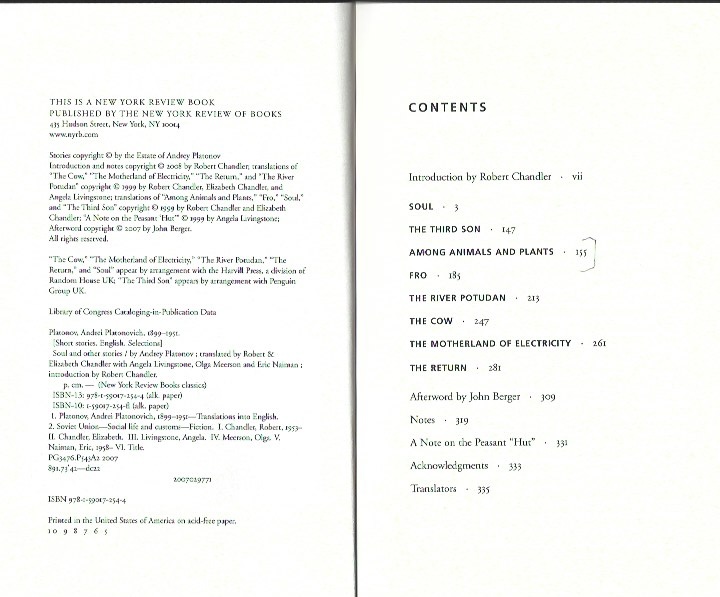

Reading discontinuously (skimming; skipping) Andrey Platonov, "Among Animals and Plants" in Soul (NYRB)

"Someone who cannot state what he means without ambiguity is not worth wasting time on."

Theodor Adorno, “Skoteinos, or How to Read Hegel” in Hegel: Three Studies, trans Shierry Weber Nicholson (MIT Press, 1993), p. 95

The only reader who does justice to Hegel is the one who does not denounce him for such indisputable weakness but instead perceives in that impulse in that weakness, who understands why this or that must be incomprehensible and in fact thereby understands it.

Hegel has a twofold expectation of his reader, not ill suited for the nature of the dialectic. The reader is to float along, to let himself be borne by the current and not force the momentary to linger. Otherwise he would change it, despite and through the greatest fidelity to it. On the other hand, the reader must develop a slow-motion procedure, to slow down the tempo at the cloudy places in such a way that they do not evaporate and their motion be seen. It is rare that these two modes of operation fall to the same act of reading. The act of reading has to separate into its polarities like the content itself.

Theodor Adorno, “Skoteinos, or How to Read Hegel” in Hegel: Three Studies, trans Shierry Weber Nicholson (MIT Press, 1993), p. 123

Shade's poem, also called "Pale Fire," is autobiographical in content,

defiantly old-fashioned in its reliance on heroic couplets, and metaphysical

in theme like much of Nabokov's own poetry.' In canto 2 Shade

recalls his daughter Hazel, an unhappy social outcast who experiments with

the occult and eventually commits suicide in college. One vignette shows

her reading a literature assignment that Shade dismisses as "some phony

modem poem" (PF 46,1. 377), but that Botkin defends in his commentary

as the work of one of "the most distinguished poets of his day" (PF 194).

Here is the scene:

Or she'd be reading in her bedroom, next

To my fluorescent lair, and you would be

In your own study, twice removed from me.

And I would bear both voices now and then:

"Mother, what's grimpen?" "What is what?"

"Grim Pen."

Pause, and your guarded scholium. Then again:

"Mother, what's chtonic?" That, too, you'd explain,

Appending: "Would you like a tangerine?"

"No. Yes. And what does sempiternal mean?"

You'd hesitate. And lustily I'd roar

The answer from my desk through the closed door.

(PF 46, II. 364-74)

This key passage meant a lot to Nabokov, for in a published response to

some early essays on his work, he praised Peter Lubin for "absolutely dazzling"

scholarship in tracing all three words to Four Quartets.^ But much

more is at stake than simply noting that Shade's phony modem poet is T. S.

Eliot and that Nabokov is willing to endorse his character's verdict. For the

story of Hazel Shade radically transforms all three words so as to pinpoint

some key reasons for Nabokov's resistance to Eliot.^

An important point of departure for the poetry-reading scene was

Edmund Wilson. In 1958, or just before he started Pale Fire, Nabokov read

Wilson's 'T.S. Eliot and the Church of England."' Though their friendship

was waning, he was so impressed with the essay that he wrote to call it

"absolutely wonderful," and insisted that "Eliot's image will never be the

same" (NWL 326). Actually Wilson says little about Eliot's poetry, but he

does sharply criticize the basic tendency of his later career, as crystallized by

his declaration for classicism in literature, royalism in politics, and Anglo-

Catholicism in religion. For Nabokov, given his father's anti-tsarist politics

and his death from the gun of a Russian monarchist, even Eliot's royalism

222 Epilogue

probably wakened conflicting feelings; but in Pale Fire he concentrates on

the religious and literary facets of Eliot's image. In line with the metaphysical

slant of John Shade's poem, every word mentioned by flazel evokes the

Anglo-Catholic spirituality of Four Quartets. But her story as a whole pointedly

transforms the meaning of the words, so that they convey a different

metaphysics while at the same time contesting Eliot's original literary

methods.

Eliot's Anglo-Catholic spirit is particularly striking in "grimpen," a local

topographical term that suitably anglicizes Dante's journey through a dark

wood. Referring to a swamp in the west of England, the word appears in

"East Coker," the second of the four quartets, whose title comes from a

village in the same region;

In the middle, not only in the middle of the way

But all the way, in a dark wood, in a bramble

On the edge of a grimpen, where is no secure foothold.'

"Chtonic," Hazel's mispronunciation of "chthonic," appears in the next

quartet, "The Dry Salvages." It establishes a more broadly Catholic context

by evoking the soul's alienation from an Aristotelian and scholastic God, the

unmoved mover:

... action were otherwise movement

Of that which is only moved

And has in it no source of movement—

Driven by daemonic, chthonic

Powers."

"Sempiternal" is used in "Little Gidding," the last quartet, to describe an

unusual day of thaw in midwinter. It launches an even broader religious

conceit, which likens this disruption of the natural cycle to a transcendence

of time attained through spiritual insight:

Midwinter spring is its own season

Sempiternal though sodden toward sundown.

Suspended in time, between pole and tropic.

When the short day is brightest, with frost and fire.

The brief sun flames the ice, on pond and ditches.

And glow more intense than blaze of branch, or brazier

Stirs the dumb spirit: no wind, but pentecostal fire."

In "Pale Fire," as Nabokov cannibalizes Eliot's language by ingeniously

making it serve his own purposes, this Anglo-Catholic metaphysics yields to

a teasingly mysterious aura of fatality. In contrast to the commentary, where

Botkin vainly looks for an omen of Hazel's death among her ambiguous

Promt over Eliot in Pale Fire 223

notes on spiritualist phenomena (PF 188-89),'^ Shade's poem reveals that

omen through Eliot's language, whose most literal meanings in Four Quartets

tell the where, when, and why of Hazel's suicide. "Grimpen" predicts

the swamp in which she will drown herself, "sempitemal" the unseasonable

thaw that makes it possible for her to fall through the ice, and "chthonic"

the state of psychological distress that led her to take her life. Moreover,

when "grimpen" is repeated as "Grim Pen," the motive behind Shade's

transformation of Eliot becomes evident, for now the word suggests a preestablished

pattern that moves relentlessly toward a tragic outcome. But,

since no first reader of the poem could be expected to grasp this point, the

grimness of fate remains an interpretation after the fact. The ultimate

sources of meaning are inscmtable before anything else, or as Shade says at

one point in his poem, they are "aloof and mute" (PF 63,1. 318). Even as

Nabokov's poet uses Eliot's words to suggest a fatalistic metaphysics,

he implies that the pattern of fate is radically unknowable except in retrospect.

Closely associated with these metaphysical differences are differences in

language use that have a direct bearing on Nabokov's attitude toward Anglo-

American high modernism as represented by Eliot. Thus Nabokov's strong

sense that ultimate meanings are inscrutable accounts for his decision to

make Eliot's words more concrete. Where so little is tmly certain, at least

the immediate and the specific can be tmsted. Hence Nabokov's techniques

of characterization and description focus on the individual and the empirical,

in contrast to Eliot's more generalized and symbolic approach.

"Chthonic" typifies the presentation of character in the Four Quartets,

which depends on first principles and discounts individuality: before Eliot

even uses this adjective, which does not apply to any particular person, he

must refer to the whole system of thought based on Aristotle's unmoved

mover. Nabokov, on the other hand, makes "chthonic" an attribute of Hazel

Shade's unique personality. By the time he introduces this term as a possible

name for her distress, she already exists as a definite character, with a

pained smile and swollen feet, with academic prizes and dateless football

weekends. Nabokov has substituted a character study grounded in specifics

for Eliot's broad typology derived from scholasticism.

This empirical approach carries over to Nabokov's descriptions, which

focus on natural particulars instead of symbols. In Eliot's picture of a midwinter

thaw, "sempiternal" is the cmcial word. It tums the natural scene

into a spiritual intuition, thus fulfilling the symbolist's aim of evoking an

enduring realm of meaning beyond this world. But in Nabokov, if "sempiternal"

is to say when Hazel's death will occur, Eliot's intention must be reversed.

Not the movement toward spiritual insight.but the original description

of spring in midwinter is the real point, as the scene of Hazel's death

makes clear:

224 Epilogue

It was a night of thaw, a night of blow

With great excitement in the air. Black spring

Stood just around the comer, shivering

In the wet starlight and on the wet ground.

The lake lay in the mist, its ice half drowned.

(PF 50-51,11.494-98)

The natural scene in itself has replaced what had been an occasion for symbolist

transcendence.

Finally, and most important, the differences in Eliot's and Nabokov's

metaphysics correspond to a sharp contrast in basic literary strategies. Implicit

in Eliot's Anglo-Catholicism is a heightened sense of cultural continuities,

especially religious and theological ones, and this sense of continuity

also explains his long-standing interest in myth as a principle of literary

organization. At the time of The Waste Land, in a comment on Joyce's Ulysses

that influenced many later definitions of modernism in the Englishspeaking

world, Eliot announced, "Instead of narrative method, we may

now use the mythical method."" Even in the generally less modernist Four

Quartets, this method is still cracial, with "grimpen" a case in point as a

west-of-England restatement of Dante's Christian metaphor from centuries

before. Nabokov, however, viewed the systematic, all-embracing use of

myth as an artistic mistake, and, as already noted in discussing the Joyce

echoes in The Gift, his Lectures on Literature in the mid-1950s had contested

Eliot's position by sharply criticizing the Homeric references in Ulysses.

Pale Fire continues the attack on another front by showing the expressive

power of narrative method, the very approach Eliot had rejected forty

years before. An ingenious story line serves to convey the mysteriousness of

destiny, the "Grim Pen" of fate that encloses Hazel Shade. The poem

thereby seeks to create a fictional world of "correlated pattern" (PF 63,1.

813), as Shade calls it, in which Hazel's story will move forward with gathering

momentum to a point where the reader can look back and recognize

Eliot's words as an omen. In a classic demonstration of those two aspects of

plot that Peter Brooks has called action and enigma," the unfolding events

and the moment of retrospeetive knowledge have joined to act out a fatalistic

metaphysics.

Because it depends so closely on an intricate plot that questions the value

of Eliot's "mythical method," the peculiar retrospective fatalism of Hazel's

story deserves to be called a narrative metaphysics. Within the poem "Pale

Fire," of course, this narrative metaphysics coexists with Shade's muchquoted

poetic metaphysics of combinational delight. For Shade, rhyme and

meter are cosmic universals, giving him a euphoric feeling of "fantastically

planned,/Richly rhymed life" where "if my private universe scans right,/So

does the verse of galaxies divine/Which I suspect is an iambic line" (PF

Proust over Eliot in Pale Fire 225

68-69,11. 969-70, 974-76). But in the end a more all-embracing narrative

structure prevails over the poetry. Shade links his poetic faith to the reasonable

certainty that he will waken the next day, but the preceding evening he

repeats his daughter's encounter with a grimmer pattern. Just as in his first

premonition of death as a child, described in canto 1 of the poem (PF 38,1.

144), he sees a gardener with a wheelbarrow (PF 69,11. 998-99). Shortly

afterwards he is mistakenly murdered by Jack Grey, an escaped convict who

believes Shade is the judge who sent him to prison.

As a reworking of Eliot, the flazel Shade episode has shuttled between

basic metaphysical assumptions and corresponding issues of literary technique.

In general outlook her story has changed the Anglo-Catholic spiritual

quest of the Four Quartets to a fatalism tinged with uncertainty, and this

awareness of uncertainty accounts for the element of intense empiricism in

Nabokov's approach.

]ohn Burt Fosterm Jr., Nabokov's Art of Memory and European Modemism (1993), 221-25

T. S Eliot, For Lancelot Andrewes: Essays on Style and Order

"Textual Sacraments: Capturing the Numinous in the Sermons of Lancelot Andrewes," Noam Reisner Renaissance Studies, Vol. 21, No. 5 (NOVEMBER 2007), pp. 662-678

T. S. Eliot, George Herbert

Stanley Eugene Fish, Seventeenth-century Prose: Modern Essays in Criticism

XCVI Sermons by the Right Honorable and Reverend Father in God, Lancelot Andrewes, Late Bishop of Winchester (London, 1629), p. 126.

George Herbert, A Priest to the Temple; Or, The Country Parson, His Character, and Rule of Holy Life (London, 1671), pp. 22–23. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A43381.0001.001?view=toc

https://archive.org/details/priesttotempleor00herb/mode/1up?ref=ol&view=theater"In Vermont, a School and Artist Fight Over Murals of Slavery"

"Created to depict the brutality of enslavement, the works are seen by some as offensive. The school wants them permanently covered. The artist says they are historically important."

(Feb. 21, 2023)

Felman, Shoshana, Literature and psychoanalysis : the question of reading, otherwise 1982

Felman, Shoshana La folie et la chose littéraire1978

Vincent Lloyd, "A Black Professor Trapped in Anti-Racist Hell" February 10, 2023

Stéphane Mallarmé, Henry Michael Weinfield (Translator), Henry Michael Weinfield (Commentary) Collected Poems of Mallarmé A Bilingual Edition (2011)

Sonnet "Ses pur ongle très-haut ..." ("De scintitlations sitôt le septour") Do the alliterative sounds "scin, si, and sept" convert the three words into the numbers cinque, six, sept (five, six, seven)?

See the last three lines:

Elle, défunte nue en le miroir, encor

Que, dans l'oubli fermé par le cadre, se fixe

De scintillations sitôt le septuor.

Maria Parrino, “His Master’s Voice: Sound Devices in Bram Stoker’s Dracula

« La voix de son maître » : dispositifs sonores dans Dracula de Bram Stoker

https://doi.org/10.4000/cve.9789

Jennifer Wicke. "Vampiric Typewriting: Dracula and Its Media." ELH, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Summer, 1992), pp. 467-493.

Avital Ronell. The Telephone Book. Technology, Schizophrenia, Electric Speech. 484 pages. Illus. Paperback. July 1991

Laurence Rickels. The Vampire Lectures. University of Minnesota Press 1999

Andreas Sommer, “Psychical Research and the Origins of American Psychology: Hugo Münsterberg, William James and Eusapia Palladino,” in Hist Human Sci. 2012 April 25 (2): 23–44.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3552602/

The very enterprise of appropriating meaning is thus reveal- ed to be the strict appropriation of precisely nothing-nothing alive, at least: "le demontage impie de la fiction et consequemment du mecanisme litteraire," writes Mallarmé, "pour étaler la piece prin-cipale ou rien (...) le conscient manque chez nous de ce qui la-haut eclate." n47

n47 "The impious dismantling of fiction and consequently of the literary mechanism as such in an effort to display the principal part or nothing, (...) the conscious lack(s) within us of what, above, bursts out and splits": Mallarme, La Musique et les Lettres, in Oeuvres Completes (Paris: Pleiade, 1945), p. 647; my translation.

p. 174

La musique et les lettres / par Stéphane Mallarmé Mallarmé, Stéphane (1842-1898). Auteur du texte. Ce document est disponible en mode texte ..

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen Chapter 1 It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

"By tea-time, however, the dose had been enough, and Mr. Bennet was glad to take his guest into the drawing-room again, and, when tea was over, glad to invite him to read aloud to the ladies. Mr. Collins readily assented, and a book was produced; but, on beholding it (for everything announced it to be from a circulating library), he started back, and begging pardon, protested that he never read novels. Kitty stared at him, and Lydia exclaimed. Other books were produced, and after some deliberation he chose Fordyce’s Sermons. Lydia gaped as he opened the volume, and before he had, with very monotonous solemnity, read three pages, she interrupted him with:

“Do you know, mamma, that my uncle Phillips talks of turning away Richard; and if he does, Colonel Forster will hire him. My aunt told me so herself on Saturday. I shall walk to Meryton to-morrow to hear more about it, and to ask when Mr. Denny comes back from town.”

Lydia was bid by her two eldest sisters to hold her tongue; but Mr. Collins, much offended, laid aside his book, and said:

“I have often observed how little young ladies are interested by books of a serious stamp, though written solely for their benefit. It amazes me, I confess; for, certainly, there can be nothing so advanta- geous to them as instruction. But I will no longer importune my young cousin.”

Then turning to Mr. Bennet, he offered himself as his antagonist at backgammon. Mr. Bennet accepted the challenge, observing that he acted very wisely in leaving the girls to their own trifling amusements. Mrs. Bennet and her daughters apologised most civilly for Lydia’s in- terruption, and promised that it should not occur again, if he would resume his book; but Mr. Collins, after assuring them that he bore his young cousin no ill-will, and should never resent her behaviour as any affront, seated himself at another table with Mr. Bennet, and prepared 48 for backgammon.

The girls stared at their father. Mrs. Bennet said only, “Nonsense, nonsense!”

“What can be the meaning of that emphatic exclamation?” cried he. “Do you consider the forms of introduction, and the stress that is laid on them, as nonsense? I cannot quite agree with you there. What say you, Mary? For you are a young lady of deep reflection, I know, and read great books and make extracts.”

Mary wished to say something sensible, but knew not how.--

Elizabeth was so much caught with what passed, as to leave her

very little attention for her book; and soon laying it wholly aside, she drew near the card-table, and stationed herself between Mr. Bingley and his eldest sister, to observe the game.

Darcy took up a book; Miss Bingley did the same; and Mrs. Hurst, principally occupied in playing with her bracelets and rings, joined now and then in her brother’s conversation with Miss Bennet.

Miss Bingley’s attention was quite as much engaged in watching Mr. Darcy’s progress through his book, as in reading her own; and she was perpetually either making some inquiry, or looking at his page. She could not win him, however, to any conversation; he merely an- swered her question, and read on. At length, quite exhausted by the attempt to be amused with her own book, which she had only chosen because it was the second volume of his, she gave a great yawn and said, “How pleasant it is to spend an evening in this way! I declare af- ter all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of anything than of a book!

Armstrong, Nancy. "The Gothic Austen." A Companion to Jane Austen.

In order to include all students in class discussion, and in order to make it easier for you to read closely and thereby improve your own writing, I have changed our discussion format for the rest of the semester. We will close read the assigned text sentence by sentence, the way we read the autobiographical story Freud tells in his essay on Gradiva earlier this semester. Discussion co-leaders and I will call on a student at random and ask that student to read a specific sentence out loud and then to close read it. If the student is unable to read the sentence closely, the co-leaders will call on another student and ask that student to read a specific sentence out loud and then to close read it. We will continue to discuss the same sentence until a student reads it closely. We will then proceed in the same fashion with the next sentence. And so on. Due to time constraints and because close reading is slow reading, we will skip parts of the assigned text, but we will always be talking and only be talking about words, syntax, punctuation, paragraphing, and narration in the text. As we move through the text, we will be able to make more general comments about parts of it. If students have comments to add on the sentence under discussion, they may raise their hands and make them once they have been called on by the co-leaders or me.

In order to learn the names of all the students in the class, I will call roll at the beginning of class. As I state on the requirements webpage, if you are late to class, I consider you absent.

Here is what I have written on the requirements webpage:

"Attendance means not only being in class, but includes completing the assigned work for each class by the time it is due and arriving to class on time. (If you arrive late to class or if you don't do the discussion questions, you are counted as absent.)

I will be asking you to learn how to do something no one may ever have asked you to do: it's called close reading. (Please do not confuse being moralistic and judgmental--"it didn't do 'x' and it should have done!"--with being critical--"why is the work doing what it is doing the way it is doing it?")."

Close reading means paying attention to language, to the words the author has used, the order in which they are used, and appreciating how well they are used. It means paying attention not to what is said but to how it is said; it means paying attention to the structure of sentences and the structure of the narrative; it means paying attention to tropes such as metaphor, metonymy, and irony, among others; it means being alert to allusions a work of literature makes to other works of literature.

See Cleanth Brooks, "The Heresy of Paraphrase," in The Well-Wrought Urn.

Close reading is a practice designed for literature, for texts that are extremely well-written. Literature is universal. Literature is often difficult to write. And it is often difficult to read. Not just anyone can write it. And not just anyone can read it closely. (If you do not know how to write a grammatical sentence or how to punctuate or how to use words correctly, you cannot learn how to read closely.) All writers of literature are excellent close readers. They know humongous amounts of (big) words.

Let me remind you of the format for discussion questions:

Example of the word document format for discussion questions due Mondays by 5:00 p.m.:

Your name in the upper left corner.

1. (Give the page number(s) or quote enough of the text for us to be able to find the passage you are discussing)

2. (Give the page number(s) or quote enough of the text for us to be able to find the passage you are discussing)

Three Big Words (on each assigned reading)

a. Write down the word and give the definition. Cut and paste the sentence where the word is used.

b. Write down the word and give the definition. Cut and paste the sentence where the word is used.

NOTE: Your discussions questions are limited to the texts and films. Do not use them as prompts to talk about something else. Ask about the formal structures of the texts and films, not about the author or historical context. Do not ask speculative questions. They cannot be answered and so are not productive for discussion.

And all the movement Charlotte Brontë remarks, from her own experience, that the writer says more than he knows, and is emphatic that this was the case with Emily. "Having formed these beings, she did not know what she had done." Of course this strikes us as no more than common sense, though Charlotte chooses to attribute it to Emily's ignorance of the world. A narrative is not a transcription of something pre-existent. And this is precisely the situation represented by Lockwood's play with the names he does not understand, his constituting out of any scribbles, a rebus for the plot of the novel he's involved in. The situation indicates the kind of work we must do when a narrative opens itself to us, and contains information in excess of what generic probability requires."

--Frank Kermode, "A Modern Way with the Classic"

New Literary History Vol. 5, No. 3 (Spring, 1974), pp. 415-434; pp. 419-20 (Bolded emphases, mine)

Required Reading:

Stephen Booth, Ed. Shakespeares Sonnets, preface, facing page facsimiles and modernized sonnets, and commentary. (Yale UP, 1977)

April 19

Required Reading:

“I should now get back to the value of unmade puns.” p. 195

Stephen Booth, Shakespeare Sonnets (Yale UP, 1977)

See also, p. 537

For other related ideas p. 537

However, see the p. 536

Note that sonnets 153 and 154 are in a poetic tradition . . . [see 45 and notes, and compare such exercises tin oxymorons to Drayton, "When I first ended, then I first began” and “Those teares, which quench my hope” [No bibliographical data given for the sources of these lines] and sonnet 30 of Spenser’s Amoretti].

Note also, p. 536

14. Vade. So Q. Dowden, adopting this form, refers to Passionate

Pilgrim, x. i, "Sweet rose, fair flower, untimely pluck'd, soon

vaded."

http://www.shakespeare-online.com/sonnets/54.html

April 24

Required Reading:

Stephen Booth, Ed. Shakespeares Sonnets, preface, facing page facsimiles of the quarto sonnets and Booth's transcription modernized , and commentary. (Yale UP, 1977)

versus Helen Vendler, ed. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets(Harvard UP, 1997)

Helen Vendler, The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets (1977)

April 26 Critic as Ho(st)LY FoOl Either You Criss or You Cross (Out or Off)

Required Reading:

GEORGE HERBERT, "LOVE (III)"

“The Real Presence of Absent Puns: George Herbert’s ‘Love (III),’” in Shakespeare Up Close: Reading Early Modern Texts, ed. Nicholas Nace, Russ McDonald, and Travis D. Williams (London: Arden Shakespeare, 2013), pp. 76-83.

Recommended Reading:

Prayer and Power- George Herbert and Renaissance Courtship

Sigmund Freud, Delusion and Dream An Interpretation in the Light of Psychoanalysis of Gradiva, Parts II, III, IV, and the postscript to the second edition, pp. 41-95

Recommended Reading:

Radical misreading of Freud's essay by Marianna Torgovnick in Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives, p. 208. The basis of her criticism of Freud is her misspelling of "Gradiva" as "Gravida."

Jacques Derrida, "Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression," pp. 53-60

Daniel Orrells, "Derrida's Impression of Gradiva: Archive Fever and Antiquity," in Derrida and Antiquity

Predatory Reading vs. Literary Criticism

How to Read a Book 1940 edition

How to Read a Book 1966 edition

How To Read A Book 1972 Edition

John T. Irwin ,"Mysteries We Reread, Mysteries of Rereading: Poe, Borges, and the Analytic Detective Story; Also Lacan, Derrida, and Johnson" MLN, Vol. 101, No. 5, Comparative Literature (Dec., 1986), pp. 1168- 1215

Cody Rose Clevidence, Dearth & God's Green Mirth (2022)

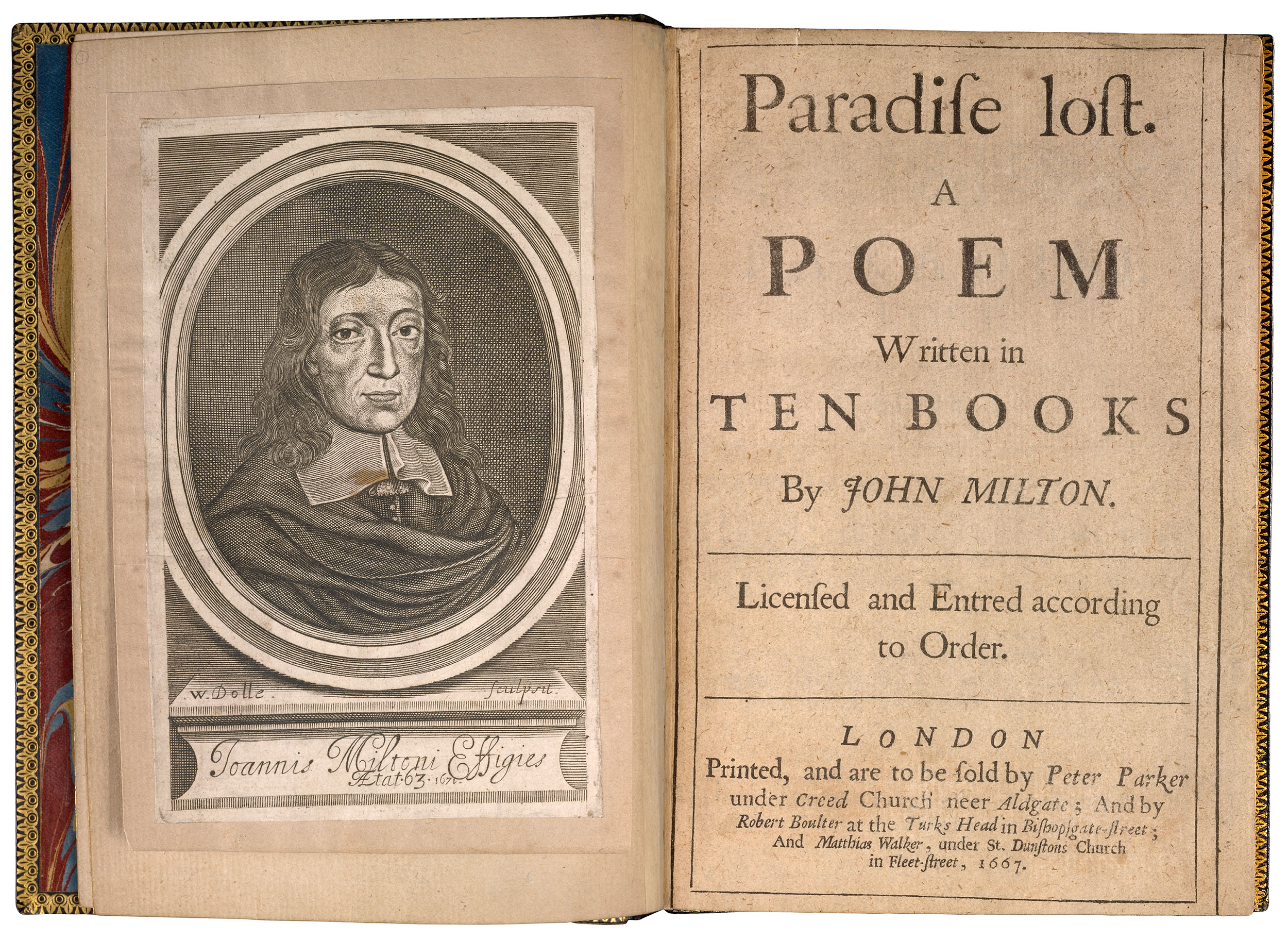

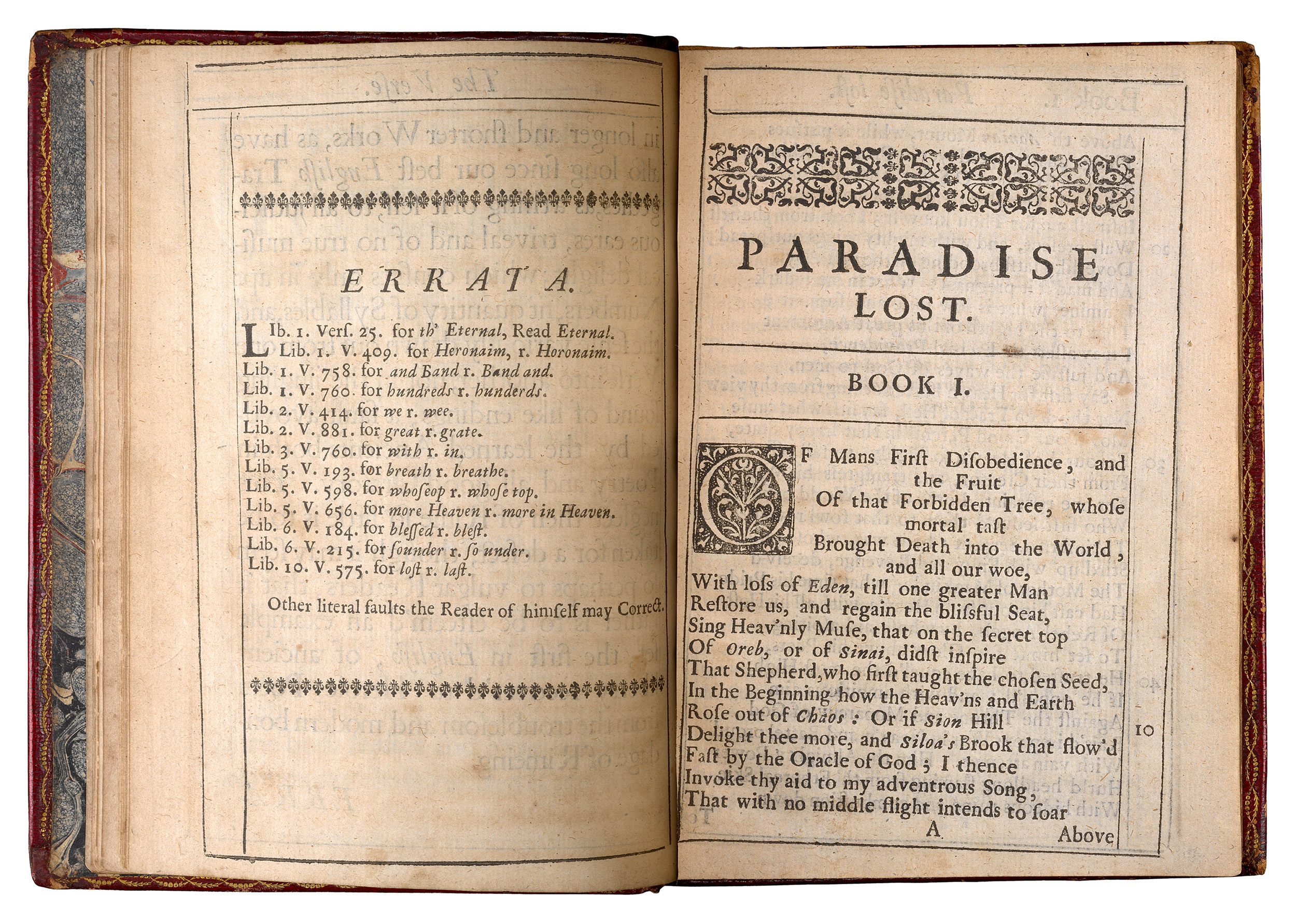

John Milton, Paradise Lost (1667 edition) / (1688 edition)

Salon des Refusés (1863)

JAMES SMITH & HORACE SMITH, REJECTED ADDRESSES: OR, THE NEW THEATRUM POETARUM (1833)

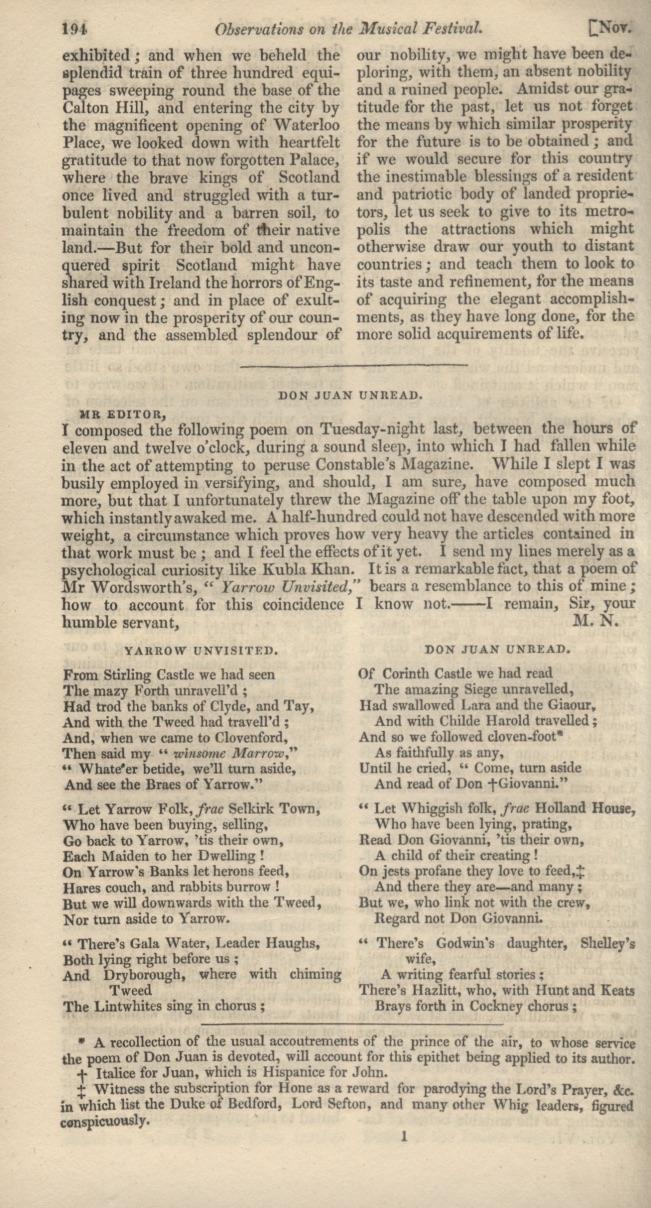

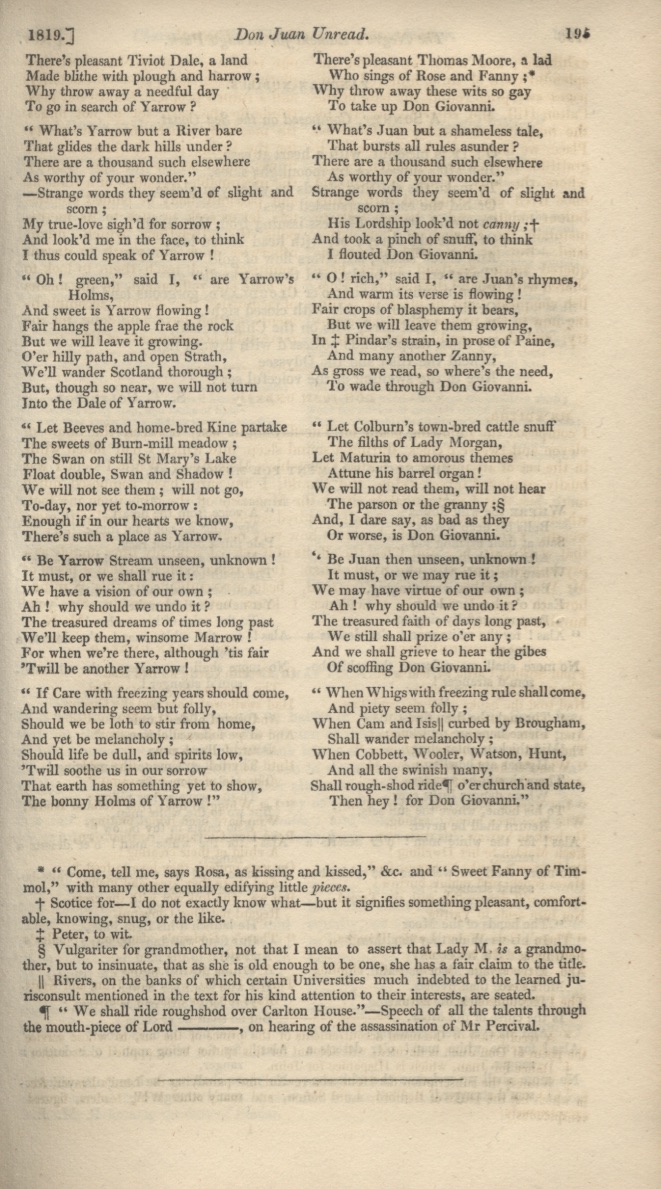

William McGinn, "Don Juan Unread" (1819)

"As gross we read, as where's the need, / To wade through Don Giovanni."

Lord Byron, Don Juan (1859)

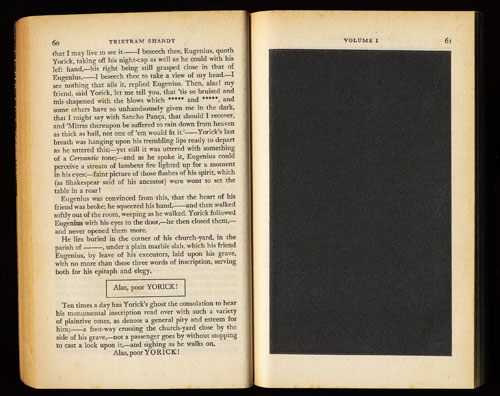

Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy, "Excummunicato" Dashed Out Writing

http://www.fulltable.com/vts/t/ts/a.htm

The Wife of Bath as one of the first cancellers of literature. Holy Fire

Wife of Bath tale book burning destruction

Reading for pleasure Chaucer

587 Whan that my fourthe housbonde was on beere,

When my fourth husband was on the funeral bier,

588 I weep algate, and made sory cheere,

I wept continuously, and acted sorry,

589 As wyves mooten, for it is usage,

As wives must do, for it is the custom,

590 And with my coverchief covered my visage,

And with my kerchief covered my face,

591 But for that I was purveyed of a make,

But because I was provided with a mate,

592 I wepte but smal, and that I undertake.

I wept but little, and that I affirm.

593 To chirche was myn housbonde born a-morwe

To church was my husband carried in the morning

594 With neighebores, that for hym maden sorwe;

By neighbors, who for him made sorrow;

595 And Jankyn, oure clerk, was oon of tho.

And Jankin, our clerk, was one of those.

596 As help me God, whan that I saugh hym go

As help me God, when I saw him go

597 After the beere, me thoughte he hadde a paire

After the bier, I thought he had a pair

598 Of legges and of feet so clene and faire

Of legs and of feet so neat and fair

599 That al myn herte I yaf unto his hoold.

That all my heart I gave unto his keeping.

600 He was, I trowe, twenty wynter oold,

He was, I believe, twenty years old,

601 And I was fourty, if I shal seye sooth;

And I was forty, if I shall tell the truth;

602 But yet I hadde alwey a coltes tooth.

But yet I had always a colt's tooth.

603 Gat-tothed I was, and that bicam me weel;

With teeth set wide apart I was, and that became me well;

604 I hadde the prente of seinte Venus seel.

I had the print of Saint Venus's seal.

605 As help me God, I was a lusty oon,

As help me God, I was a lusty one,

606 And faire, and riche, and yong, and wel bigon,

And fair, and rich, and young, and well fixed,

607 And trewely, as myne housbondes tolde me,

And truly, as my husbands told me,

608 I hadde the beste quoniam myghte be.

I had the best pudendum that might be.

609 For certes, I am al Venerien

For certainly, I am all influenced by Venus

610 In feelynge, and myn herte is Marcien.

In feeling, and my heart is influenced by Mars.

611 Venus me yaf my lust, my likerousnesse,

Venus me gave my lust, my amorousness,

612 And Mars yaf me my sturdy hardynesse;

And Mars gave me my sturdy boldness;

613 Myn ascendent was Taur, and Mars therinne.

My ascendant was Taurus, and Mars was therein.

614 Allas, allas! That evere love was synne!

Alas, alas! That ever love was sin!

615 I folwed ay myn inclinacioun

I followed always my inclination

616 By vertu of my constellacioun;

By virtue of the state of the heavens at my birth;

617 That made me I koude noght withdrawe

That made me that I could not withdraw

618 My chambre of Venus from a good felawe.

My chamber of Venus from a good fellow.

619 Yet have I Martes mark upon my face,

Yet have I Mars' mark upon my face,

620 And also in another privee place.

And also in another private place.

621 For God so wys be my savacioun,

For as God may be my salvation,

622 I ne loved nevere by no discrecioun,

I never loved in moderation,

623 But evere folwede myn appetit,

But always followed my appetite,

624 Al were he short, or long, or blak, or whit;

Whether he were short, or tall, or black-haired, or blond;

625 I took no kep, so that he liked me,

I took no notice, provided that he pleased me,

626 How poore he was, ne eek of what degree.

How poor he was, nor also of what rank.

627 What sholde I seye but, at the monthes ende,

What should I say but, at the month's end,

628 This joly clerk, Jankyn, that was so hende,

This jolly clerk, Jankin, that was so courteous,

629 Hath wedded me with greet solempnytee,

Has wedded me with great solemnity,

630 And to hym yaf I al the lond and fee

And to him I gave all the land and property

631 That evere was me yeven therbifoore.

That ever was given to me before then.

632 But afterward repented me ful soore;

But afterward I repented very bitterly;

633 He nolde suffre nothyng of my list.

He would not allow me anything of my desires.

634 By God, he smoot me ones on the lyst,

By God, he hit me once on the ear,

635 For that I rente out of his book a leef,

Because I tore a leaf out of his book,

636 That of the strook myn ere wax al deef.

So that of the stroke my ear became all deaf.

637 Stibourn I was as is a leonesse,

I was as stubborn as is a lioness,

638 And of my tonge a verray jangleresse,

And of my tongue a true chatterbox,

639 And walke I wolde, as I had doon biforn,

And I would walk, as I had done before,

640 From hous to hous, although he had it sworn;

From house to house, although he had sworn the contrary;

641 For which he often tymes wolde preche,

For which he often times would preach,

642 And me of olde Romayn geestes teche;

And teach me of old Roman stories;

643 How he Symplicius Gallus lefte his wyf,

How he, Simplicius Gallus, left his wife,

644 And hire forsook for terme of al his lyf,

And forsook her for rest of all his life,

645 Noght but for open-heveded he hir say

Because of nothing but because he saw her bare-headed

646 Lookynge out at his dore upon a day.

Looking out at his door one day.

647 Another Romayn tolde he me by name,

Another Roman he told me by name,

648 That, for his wyf was at a someres game

Who, because his wife was at a midsummer revel

649 Withouten his wityng, he forsook hire eke.

Without his knowledge, he forsook her also.

650 And thanne wolde he upon his Bible seke

And then he would seek in his Bible

651 That ilke proverbe of Ecclesiaste

That same proverb of Ecclesiasticus

652 Where he comandeth and forbedeth faste

Where he commands and strictly forbids that

653 Man shal nat suffre his wyf go roule aboute.

Man should suffer his wife go wander about.

654 Thanne wolde he seye right thus, withouten doute:

Then would he say right thus, without doubt:

655 `Whoso that buyldeth his hous al of salwes,

`Whoever builds his house all of willow twigs,

656 And priketh his blynde hors over the falwes,

And spurs his blind horse over the open fields,

657 And suffreth his wyf to go seken halwes,

And suffers his wife to go on pilgrimages,

658 Is worthy to been hanged on the galwes!'

Is worthy to be hanged on the gallows!'

659 But al for noght, I sette noght an hawe

But all for nothing, I gave not a hawthorn berry

660 Of his proverbes n' of his olde sawe,

For his proverbs nor for his old sayings,

661 Ne I wolde nat of hym corrected be.

Nor would I be corrected by him.

662 I hate hym that my vices telleth me,

I hate him who tells me my vices,

663 And so doo mo, God woot, of us than I.

And so do more of us, God knows, than I.

664 This made hym with me wood al outrely;

This made him all utterly furious with me;

665 I nolde noght forbere hym in no cas.

I would not put up with him in any way.

666 Now wol I seye yow sooth, by Seint Thomas,

Now will I tell you the truth, by Saint Thomas,

667 Why that I rente out of his book a leef,

Why I tore a leaf out of his book,

668 For which he smoot me so that I was deef.

For which he hit me so hard that I was deaf.

669 He hadde a book that gladly, nyght and day,

He had a book that regularly, night and day,

670 For his desport he wolde rede alway;

For his amusement he would always read;

671 He cleped it Valerie and Theofraste,

He called it Valerie and Theofrastus,

672 At which book he lough alwey ful faste.

At which book he always heartily laughed.

673 And eek ther was somtyme a clerk at Rome,

And also there was once a clerk at Rome,

674 A cardinal, that highte Seint Jerome,

A cardinal, who is called Saint Jerome,

675 That made a book agayn Jovinian;

That made a book against Jovinian;

676 In which book eek ther was Tertulan,

In which book also there was Tertullian,

677 Crisippus, Trotula, and Helowys,

Crisippus, Trotula, and Heloise,

678 That was abbesse nat fer fro Parys,

Who was abbess not far from Paris,

679 And eek the Parables of Salomon,

And also the Parables of Salomon,

680 Ovides Art, and bookes many on,

Ovid's Art, and many other books,

681 And alle thise were bounden in o volume.

And all these were bound in one volume.

682 And every nyght and day was his custume,

And every night and day was his custom,

683 Whan he hadde leyser and vacacioun

When he had leisure and spare time

684 From oother worldly occupacioun,

From other worldly occupations,

685 To reden on this book of wikked wyves.

To read in this book of wicked wives.

686 He knew of hem mo legendes and lyves

He knew of them more legends and lives

687 Than been of goode wyves in the Bible.

Than are of good women in the Bible.

688 For trusteth wel, it is an impossible

For trust well, it is an impossibility

689 That any clerk wol speke good of wyves,

That any clerk will speak good of women,

690 But if it be of hooly seintes lyves,

Unless it be of holy saints' lives,

691 Ne of noon oother womman never the mo.

Nor of any other woman in any way.

692 Who peyntede the leon, tel me who?

Who painted the lion, tell me who?

693 By God, if wommen hadde writen stories,

By God, if women had written stories,

694 As clerkes han withinne hire oratories,

As clerks have within their studies,

695 They wolde han writen of men moore wikkednesse

They would have written of men more wickedness

696 Than al the mark of Adam may redresse.

Than all the male sex could set right.

697 The children of Mercurie and of Venus

The children of Mercury (clerks) and of Venus (lovers)

698 Been in hir wirkyng ful contrarius;

Are directly contrary in their actions;

699 Mercurie loveth wysdam and science,

Mercury loves wisdom and knowledge,

700 And Venus loveth ryot and dispence.

And Venus loves riot and extravagant expenditures.

701 And, for hire diverse disposicioun,

And, because of their diverse dispositions,

702 Ech falleth in otheres exaltacioun.

Each falls in the other's most powerful astronomical sign.

703 And thus, God woot, Mercurie is desolat

And thus, God knows, Mercury is powerless

704 In Pisces, wher Venus is exaltat,

In Pisces (the Fish), where Venus is exalted,