Course Description

Richard Burt

LIT 4930

Narratology and the Incomplete Complete Novel

NO KNOWLEDGE OF FRENCH IS REQUIRED FOR THIS COURSE.

I don't do trigger warnings. I considered myself an adult when I went to college at age 18. Professors and graduate student T.A.s felt the same way about their students. I would have been insulted by any professor or told me I might feel a certain way about a film or a book before I'd had a chance to see it or read it myself. I was sometimes upset by a film I saw or a book I read. I still am. I felt and still feel that being disturbed by literature or film was part of learning. And I didn't think--and still don't--that talking about it necessarily makes it any less emotionally disturbing. If you tend to be "triggered," you probably should not take a course on literature or film. imo. No judgment.

“Too much clarity darkens.”

— Blaise Pascal, Pensées.

This is an intellectually and emotionally ambitious class. You will need to have the amibition to read Proust and Genette if you want to take this class. You have to want to learn.

The aim of the class is to read Marcel Proust together with Gérard Genette. To achieve that aim, we will alternate between reading Proust and reading Genette much of the time. The assigned readings by Genette focus on Proust and narration.

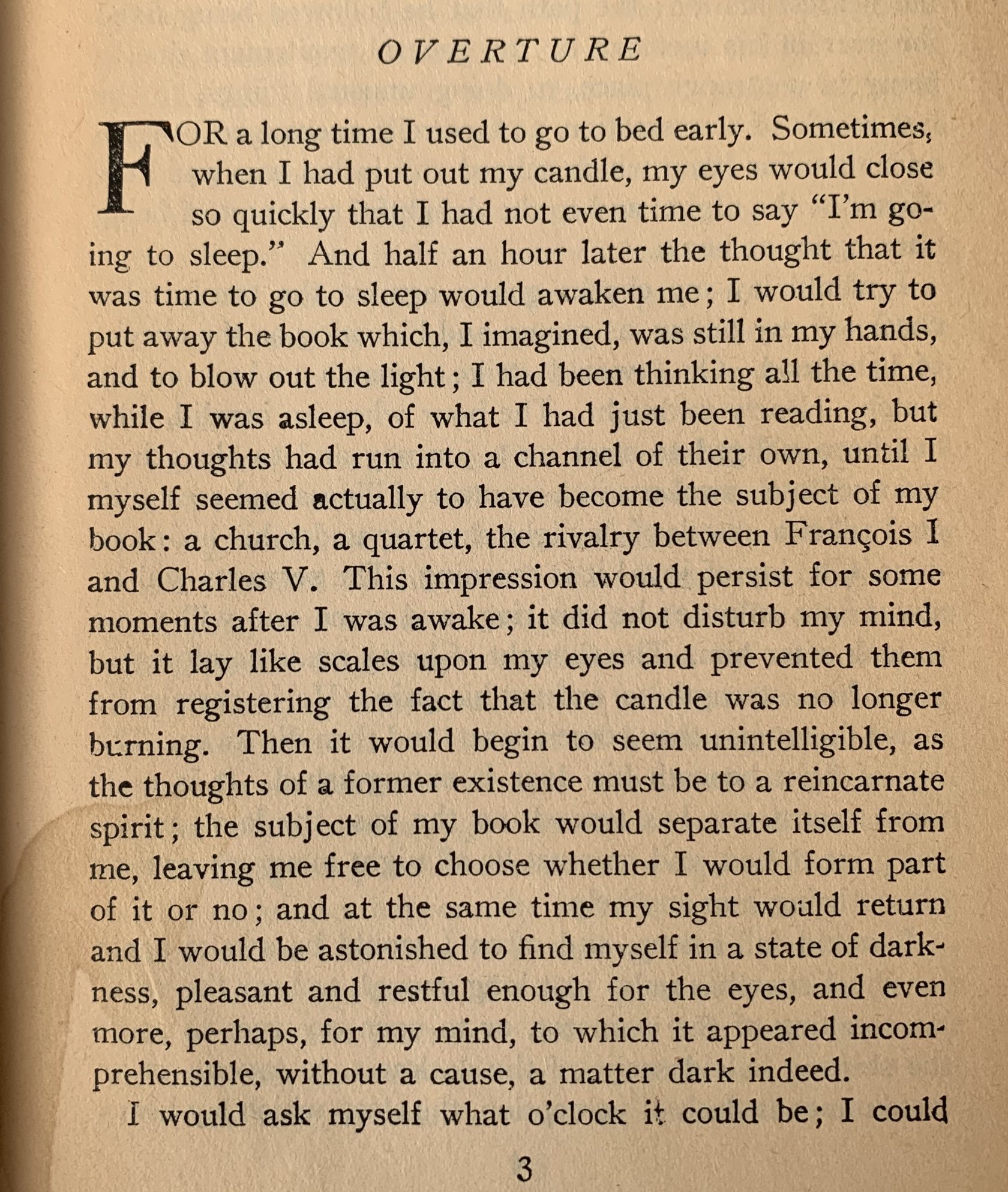

In most classes on a novel, students are told to read the novel the same way they would read any book, namely, from beginning, starting on the first page, and ending on the last. A critical edition would supply annotations, and guides to the Recherche include summaries, quotations, and commentaries. Everything is directed toward basic reading comprehension. This kind of reading is criticism at it its most basic, and although limited, it has the benefit of being very close to the text. we will be doing what Gérard Genette calls "structured reading." Instead of reading the Recherche head on by reading it in order, we will overcome its difficulty by reading it out of order, breaking up Swann's Way with digressions, so to speak, into literary theory (mostly essay and boook chapters by Genette), and leaping ahead to the last novel, Time Found Again, aka Time Regained. We will read also read scenes from other novels related to the title of this course that bear on the novel's completion and incompletion. By proceeding in this eccentric manner, we will be able to read the Recherche in two ways, attending not only to any one of the seven novels we are reading but also gaining a sense of that novel relates to the Recherche as a whole. And we will then be in a positition to ask not only what is Proustian but the more interesting and challenging question, What is Proustian about Proust?

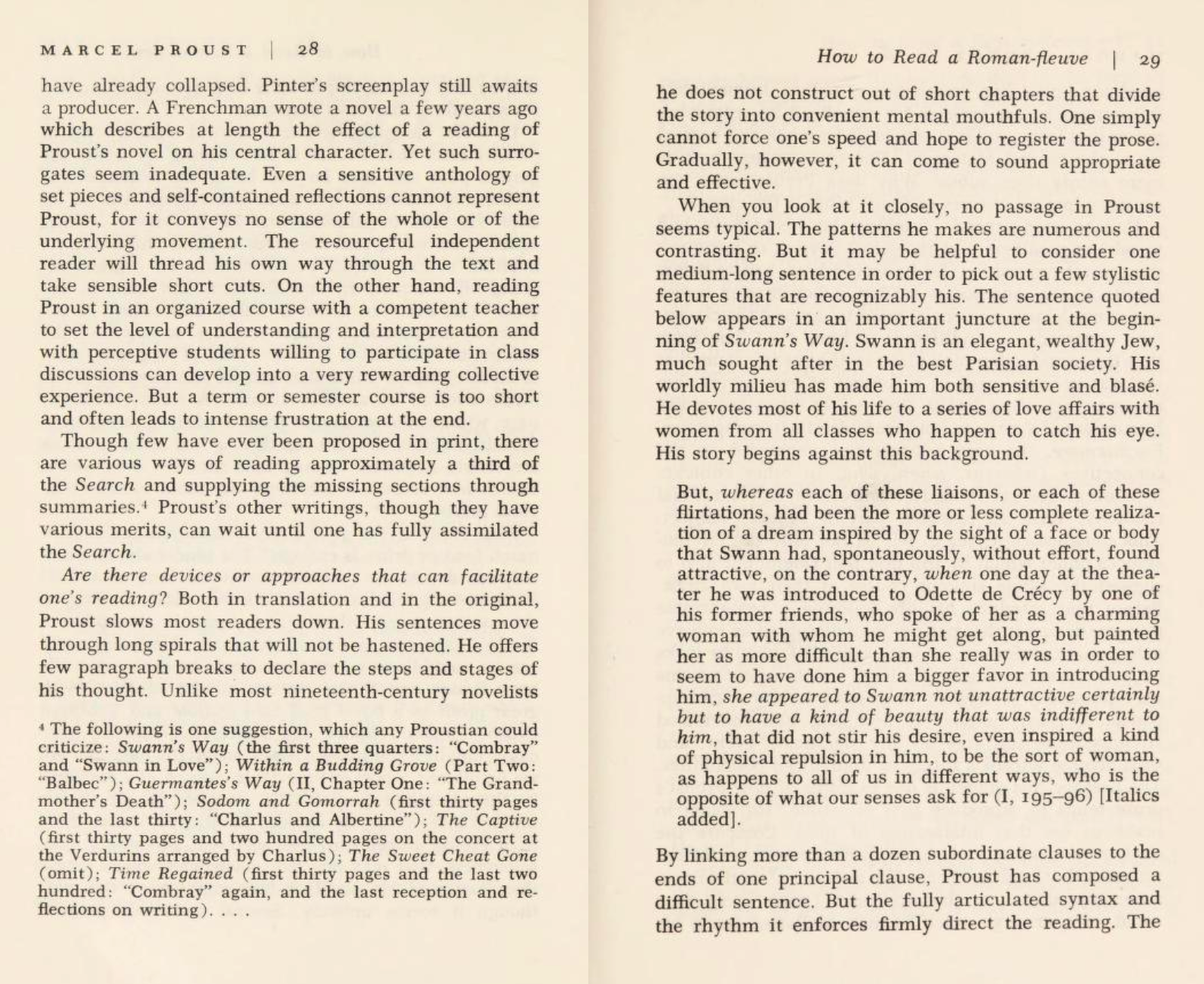

We will not read the novel in chronological order, nor will we read the entire novel. Why not? Well, it's too long. In Search of Lost Time: Proust 6-pack (Modern Library Classics) is 4,211 pages and a 1,052,750 word count; the novel made the Guiness Book of World Records). One writer of a reader's guide to Proust asks "How many of the three thousand pages do you need to read?" His answer is "No," and offers his reader his own prime cuts. Nor will we read skip ahead and read the novel's "greatest hits" in the order in which they occur. We will read all of Swann's Way, but we interrupt our reading of it several times. The problem with reading Proust one page at a time is that you may give up, as many people have. This course is a kind of advanced introduction to the novel. I will ask you to pretend that you have already novel and are now rereading. So we will use Proust's metaphor of binoculars to read the novel with two perspectives, reading for comprehension and appreciation (characterization, plot, theme, beauty) but also reading with a particular critical issue in mind, like Proust's digressions, for example. Or his use of metaphor. Or his syntax.

What does all this mean? It means that we will read the novel in a fragmentary way (see Adorno) and follow critics who have an incredible command of the novel and who touch on many of the most important parts of the novel, often the parts writers of guides to the novel or overviews of it miss, and making connections between parts that may be hundreds of pages or even several novels apart. And we will also compare Proust's famously long sentences to his relatively brief one sentence aphorisms or to passages that may be aptly regarded as what Harold Bloom calls "wisdom literature." (The novel is kind of an encyclopedia.)

We'll take our leads from Roland Barthes and Theodor Adorno's "Short Commentaries on Proust"

Roland Barthes, "It All Comes Together” How did Marcel Proust become a great writer?"

Proust's novel is concerned with the way characters become fragmentary in old age.

"As I looked at her, I did not start dreaming of the part my admiration

of Bergotte, whom she had also forgotten, had formerly played in

my love of her for I now only thought of Bergotte as the author of his

books, without remembering, except during rare and isolated flashes, my

emotion when I was introduced to him, my disappointment, my astonishment

at his conversation in the drawing-room with the white rugs,

full of violets, where such a number of lamps were brought so early and

placed upon so many different tables. All the memories which composed

the original Mlle Swann were, in fact, foreshortened by the Gilberte of

now, held back by the magnetic attraction of another universe, united to

a sentence of Bergotte and bathed in the perfume of hawthorn. The fragmentary

Gilberte of today listened smilingly to my request and setting

herself to think, she became serious and appeared to be searching for

something in her head."

--Time Recaptured

Proust's radiography / X-ray metaphors and

The Man with the X-Ray Eyes(dir. Roger Corman, 1963)

In Search of Lost Time, Volume I Swann's Way (A Modern Library E-Book)

Swann's Way In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1 (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition E-Book)

LISTEN to the original, unrevised Montcrieff translation of Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time Complete Volumes read by John Rowe on Audible.com)

FREE ONLINE:

Marcel Proust, Swann's Way Trans Montcrieff, Kilmartin, Enright

In Search of Lost Time: Volume 1 Swann's Way

on archive.org: "Full text of In Search Of Lost Time ( Complete Volumes)," a dipliomatic transcription in html

In Search Of Lost Time (Complete Volumes), a digital facsimile. Both are searchable.

Ebooks are available for both the Modern Library

and the more recent and more expensive

except for the Penguin translation of Finding Time Again. It is not available as an ebook, but I strongly recommend you get the print paperback of the Penguin edition of Finding Time Again trans. Ian Patterson. I ordered copies through the UF bookstore, but you may have to order a copy through an online vendor.

--Ian Patterson , "Introduction" (and Sample Pages) Marcel Proust, Finding Time Again

You may compare some pages from Patterson's translation to the Modern Library translation (on google books) or Amazon.

Some of the Modern Library editions are available on Kindle for as low as 99 cents.

William C. Carter has revised the first four volumes of original Montcrieff translations of In Search of Lost Time for Yale UP. And in two different reviews, both with the same title, Carter has trashed both the Penguin translations and the original Montcrieff translation:

William C. Carter, "Lost in Translation" Modernism/modernity Johns Hopkins University Press Volume 12, Number 4, November 2005 pp. 695-704

William C. Carter, "Lost in Translation: Proust and Scott Moncrieff"

This scholar has in turn trashed Carter's translation: "Style Over Substance," Boston Review. LOL

Marcel Proust (Author), William C. Carter (Editor)

Swann's Way: In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1

Presently the course of the Vivonne became choked with water-plants. At first they appeared singly, a lily, for instance, which the current, across whose path it had unfortunately grown, would never leave at rest for a moment, so that, like a ferry-boat mechanically propelled, it would drift over to one bank only to return to the other, eternally repeating its double journey.

-Marcel Proust, Swann's Way

In fact each moment of the Recherche appears in a sense twice over: first in the Recherche as the birth of a vocation and second in the Recherche as the exercise of this vocation: but these two are not given to the reader together, and it is the lot of the reader informed in extremis that the book he has just read remains to be written and that this book is more or less (but only more or less) the one he has just read --to go back to those distant pages, to the childhood at Combray, the evening at the Guermantes, the death of Albertine, which he had read as safely deposited, gloriously embalmed in a finished work, and which he must now read again, identical in fact but a little different, as if in abeyance, still unburied, anxiously stretching forward an as yet unfinished work, and conversely, forever. Thus, not only is the Recherche du temps perdu, as Blanchot says, a "completed-uncompleted" work, but its very reading is competed in incompletion, forever in suspense, forever 'to be taken up again' since the object of that reading is constantly thrown into a dizzying rotation.

--Gerard Genette, Figures of Literary Discourse, pp. 203-28, to p. 222.

Proust's work is a complete-incomplete work.

--Maurice Blanchot, "The Experience of Proust " in The Book to Come, pp. 11-24; to p. 24.

Pierre Bayard wrote an optimistic, clever book of criticism entitled: How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read. This course will ask questions sparked by his title: What happens if the author of the book you haven’t read never finished the book? What if it was published posthumously by different editors who didn’t agree on what the author did or did not write? More broadly, what is the relation between narration and narrative completion, between talking about a book and telling someone about it? We will pursue these questions by reading Gérard Genette’s works on narrative and on a novel to which Genette frequently turns, namely, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Maurice Blanchot and Genette’s description of Proust’s novel an “incomplete complete novel” is the inspiration for this course. We will also read selections from an unfinished novel Bayard discusses written by Robert Musil and entitled The Man without Qualities. And we will also devote some time to occasionally humorous controversies over English translations of Proust’s novel. Discussion questions on the reading due before each class; co-lead class twice; three short papers.Why a course on narratology and Proust when narratology concerns all literary and non-literary works? Because Gérard Genette, the leading narratologist and literary theorist of the paratext, wrote a book on narrative and Proust and wrote an article on the Proustian paratext.

Proust was his own source text. His maid wrote a biography of him entitled Monsieur Proust all about his life as a writer. He wrote drafts of parts of In Search of Lost Time but did not publish them. Marcel includes a fragment of his first (unpublished) coThe Lemoine Affair, a book we will not read either, sadly.

"Refound here the American student with whom we had coffee last Saturday, the one who was looking for a thesis subject (comparative literature), I suggested to her something on the telephone in literature of the 20th century (and beyond), starting with, for example, the telephone lady in Proust or the figure of the American operator, and then asking the question of the effects of the most advanced telematics on whatever would still remain of literature. I spoke to her about microprocessors and computer terminals, she seemed somewhat disgusted. She told me that she still loved literature (me too, I answered her, mais si, mais si). Curious to know what she understood by this."

--Jacques Derrida, The Post Card, p. 204

"D'une lecture à l'autre, on ne saute jamais les mêmes passages" (From one reading to another, one never skips the same passages), [Roland Barthes] writes in Le Plaisir du texte (1973).

THE LEMOINE AFFAIR MARCEL PROUST; TRANSLATED BY. CHARLOTTE MANDELL. P. CM.

Christine M. Cano.Proust's deadline (University of Illinois Press, c2006). PQ2631.R63 A77387 2006

Full text of "Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method"

Sainte-Beuve championed a form of biographical criticism that saw texts as morally and intellectually inseparable from their writers. Here is Sainte-Beuve, as quoted by Proust:

So long as one has not asked an author a certain number of questions and received answers to them, though they were only whispered in confidence, one cannot be sure of having a complete grasp of him, even though these questions might seem at the furthest remove from the nature of his writings. What were his religious views? How did he react to the sight of nature? How did he conduct himself in regard to women, in regard to money? Was he rich, was he poor?[1]

Such queries led Sainte-Beuve to rank Bernard, Vinet, Molé, Verdelin, Meilhan, and Azyr among the great writers of his time, to dismiss Baudelaire and Balzac as vulgar and Hugo as overly political. History has not been on Sainte-Beuve’s side, and neither was Proust. À la recherche, the novel that grew out of this early piece of literary criticism, persuasively refutes Sainte-Beuve’s method by bringing into contrast the sometimes sordid lives of its characters and the emotional nuance of their experiences of the world. At the time Proust wrote Contre Sainte-Beuve, however, this refutation was still taking shape.

--Michael Shapiro, Contre Saint-Beuve

Paul de Man "Reading (Proust)" in Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, RiIke, and Proust. New Haven and London. Yale University Press (1979),pp.57-7

Gerald Prince, “Narratology,” in The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism, ed. Michael Groden and Martin Kreiswirth (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), 524–28.

Gerald Prince, A Dictionary of Narratology (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003)

Mieke Bal, Introduction to the Theory of Narrative (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985)

Mieke Bal, "Tell-Tale Theories." Poetics Today, 7:3 (1984)

Millicent Bell, “Narrative Gaps / Narrative Meaning,” Raritan: A Quarterly Review 6, no.1 (1986): 84–102.

Cohn, Dorrit. (Correspondence with Gerard Genette) "Nouveaux nouveaux discours du recit" Poetique, 61 (1985), 101-09

Christine Brooke-Rose, "Stories, Theories, and Things," New Literary History Vol. 21, No. 1, (Autumn, 1989), pp. 121-131

Herrnstein-Smith, Barbara. "Narrative Versions, Narrative Theories." Critical Inquiry (1980), 213-236.

Todorov, Tzvetan. "Les categories du recit litteraire." Communications, 8 (1968) 125-51

Georges Poulet The Metamorphoses of the circle 1966

Georges Poulet, Studies in Human Time 1959

Georges Poulet, Proustian Space 1977

David Ellison, A Reader's Guide to Proust's 'In Search of Lost Time' 2010

Marcel Proust, On Reading Ruskin (Prefaces to La Bible D'Amiens and Sesame Et Les Lys, with Se) 2009

Gilles Deleuze, Proust and Signs: The Complete Text (2004)

Marcel Proust, A la recherche du temps perdu. Tome 4 ; éd. pub. sous la dir. de Jean-Yves Tadié avec, pour ce vol., la collab. d'Yves Baudelle, Anne Chevalier, Eugène Nicole, Pierre-Louis Rey,--[et al.] Paris : Gallimard, c1989. PQ2631.R63 A7 1989

Pierre Bayard.Le hors-sujet : Proust et la digression Paris : Editions de Minuit, 1996.

MARCEL PROUST, À la recherche du temps perdu. Édition publiée sous la direction de JEAN-YVES TADIÉ Tome I. (Pléiade). Paris, Gallimard, 1987.

MARCEL PROUST: Du côté de chez Swann. Édition présentée et annotée par ANTOINE COMPAGNON. (Folio). Paris, Gallimard, 1988.

MARCEL PROUST: Du côté de chez Swann. Édition établie sous la direction de JEAN MILLY. Paris, Flammarion, 1987.

MARCEL PROUST: Un amour de Swann. Texte présenté et commenté par MICHEL RAIMOND. Illustrations d' ANDRÉ BRASILIER. Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1987.

ALISON FINCH French Studies, Volume XLIII, Issue 1, January 1989, Pages 104–110, https://doi.org/10.1093/fs/XLIII.1.104

Proust et la Strategie Litteraire avec des Lettres de Marcel Proust a Rene Blum, Bernard Grasset et Louis Brun, 1954

French Edition by Leon Pierre-Quint (Author), Correa Buchet/Chastel (Editor)

“It All Comes Together ”How did Marcel Proust become a great writer?

Roland Barthes, MONDAY, MAY 16, 2016

Marcel Proust (1871-1922): Criticism in English

Adorno, Theodor W. "Short Commentaries on Proust." Notes to Literature, edited by Rolf Tiedemann, translated by S.W. Nicholsen, vol. 1, Columbia University Press, 1991, pp. 174-184.

Adorno, Theodor W. "On Proust." Notes to Literature, edited by Rolf Tiedemann, translated by S.W. Nicholsen, vol. 2, Columbia University Press, 1991, pp. 312-317.

Genette, Gérard. "Time and Narrative in À la Recherche du temps perdu." Aspects of Narrative: Selected Papers from the English Institute, edited by J. Hillis Miller, Columbia University Press, 1971, pp. 93-118.

Genette, Gérard. "Proust and Indirect Language." Figures of Literary Discourse, translated by Alan Sheridan, Columbia University Press, 1982, pp. 229-295.

Genette, Gérard. "Proust Palimpsest." Figures of Literary Discourse,translated by Alan Sheridan, Columbia University Press, 1982, pp. 203-228.

Genette, Gérard. "The Proustian Paratexte." Substance, vol. 17, no. 2, 1988, pp. 63-77.

Shattuck, Roger. "Proust's Stilts." Yale French Studies, vol. 34, 1965, pp. 91-98.

Bersani, Leo. "Proust and the Art of Incompletion." Aspects of Narrative: Selected Papers from the English Institute, edited by J. Hillis Miller, Columbia University Press, 1971, pp. 119-142.

The Living Handbook of Narratology

Samuel Beckett, Proust (1931)

Vincent Descombes, Proust: Philosophy of the Novel (1992)

Poetics Today Vol. 11, No. 2, Summer, 1990 Narratology Revisited I

Poetics Today Vol. 11, No. 4, Winter, 1990 Narratology Revisited II

| David R. Ellison. | |||

| Author: Ellison, David R. | |||

| Published: Baltimore, Md. : Johns Hopkins University Press, c1984. | |||

book book |

|||

| Read this E-book (Temporary Access) |

|||

UF LIBRARY WEST General Collection |

PQ2631.R63 Z579 1984 | ||

In Search of Lost Time, Volume VI: Time Regained Reader’s Guide

Please ignore everything below:

Jacques Derrida, "Le facteur de la vérité" ("The Factor / Purveyor of Truth"; "facteur" can mean both "postman" and "factor" in French) in The Post Card, pp. 412-96. (Read this translation by Alan Bass, not the translation by Jeffrey Mehlman in Yale French Studies).

Derrida, For the Love of Lacan in Resistances

Juan Luis Borges, "Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote"

Carlo Ginzburg, Clues

Sigmund Freud,The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Chapter Nine, "Symptomatic and Chance Actions" and Chapter Ten, "Errors."

Required Reading: Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Sections 1-IV (1 though IV, including IV). Bring a copy of the book in print or a print out on paper to class (Kindles, iphones, lap top computers, etc., will not be allowed.

Required Reading: Edgar Allen Poe, "The Purloined Letter"

Required Reading: Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Sections V-VI (the rest of the book). Bring a copy of the book in print or a print out on paper to class (Kindles, iphones, lap top computers, etc will not be allowed). Recommended: Sigmund Freud, "A Note upon the Mystic Writing Pad"

Required Reading: Jacques Derrida, "To Speculate--On 'Freud'" in The Post Card, 257-291 ("1. Notices (Warnings"). Bring a copy of the book in print or a print out a copy on paper and bring it with you to class (Kindles, iphones, lap top computers, etc., will not be allowed).

Recommended: Jacques Derrida, "Differance"; Jacques Derrida, "The Parergon"

Required Reading: Jacques Lacan, "Seminar on the Purloined Letter" (click on link to left for pdf)

Recommended Readings: (T.B.R.S.,P.) Wilhelm Jentsch, "The Uncanny" ; E.T.A. Hoffmann, The Sandman; Ernst Mach, Analyse der Empfindungen (The Analysis of Sensationsand the Relation of the Physical to the Psychical), cited

The apparent permanency of the ego consists chiefly in the single fact of its continuity, in the slowness of its changes. The many thoughts and plans of yesterday that are continued today, and of which our environment in waking hours incessantly reminds us (whence in dreams the ego can be very indistinct, doubled, or entirely wanting), and the little habits that are unconsciously and involuntarily kept up for long periods of time, constitute the groundwork of the ego. There can hardly be greater differences in the egos of different people, than occur in the course of years in one person. When I recall today my early youth, I should take the boy that I then was, with the exception of a few individual features, for a different person, were it not for the existence of the chain of memories. Many an article that I myself penned twenty years ago impresses me now as something quite foreign to myself. The very gradual character of the changes of the body also contributes to the stability of the ego, but in a much less degree than people imagine. Such things are much less analysed and noticed than the intellectual and the moral ego. Personally, people know themselves very poorly. When I wrote these lines in 1886, Ribot's admirable little book, The Diseases of Personality (second edition, Paris, 1888, Chicago, 1895), was unknown to me. Ribot ascribes the principal role in preserving the continuity of the ego to the general sensibility. Generally, I am in perfect accord with his views.

Ernst Mach, The Analysis of Sensations (1897). Dover Edition, 1959;

Translation: by C M Williams and Sydney Waterlow.

Having recalled this, and having taken this precaution as a matter of principle, I am not doing what one ought to do and cannot do it with you in a seminar. I cannot do all that again with you here for at least two reasons, as I was saying. The one has to do with the obvious lack of time: it would take us years. The other, less obvious, is that I also believe in the necessity, sometimes, in a seminar the work of which is not simply reading, in the necessity, and even the fecundity, when I’m optimistic and confident, of a certain number of leaps, certain new perspectives from a turn in the text, from a stretch of path that gives you another view of the whole, like, for example, when you’re driving a car on a mountain road, a hairpin or a turn, an abrupt and precipitous elevation suddenly gives you in an instant a new perspective on the whole, or a large part of the itinerary or of what orients, designs, or destines it. And here there intervene not only each person’s reading-idioms, with their history, their way of driving (it goes without saying that each of my choices and my perspectives depends broadly here, as I will never try to hide, on my history, my previous work, my way of driving, driving on this road [I first mistakenly transcribed "read" in place of "road,"R.B.], on my drives, desires and phantasms, even if I always try to make them both intelligible, shareable, convincing and open to discussion) [here there intervene, not only each person’s reading-idioms, with their history, their way of driving] in the mountains or on the flat, on dirt roads or on highways, following this or that map, this or that route, but also the crossing, the decision already taken and imposed by you by fiat as soon as it was proposed to you, to read a given seminar by Heidegger and Robinson Crusoe, i.e., two discourses also on the way and on the path which can multiply perspectives from which two vehicles can light up, their headlights crossing, the overall cartography and the landscape in which we are traveling and driving together, driving on all these paths interlaced, intercut, overloaded with bridges, fords, no entries or one-way streets, etc.

Jacques Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign, Vol. 2, (2012) 206

Ernst Mach, The Analysis of Sensations (1897). Dover Edition, 1959;

Translation: by C M Williams and Sydney Waterlow.