"Should I take a course with Burt? "

OK, if you enrolled in this class only because it fits your schedule and you could care less about the course content, I urge you to drop it asap and find another class. Students who skip class do not pass.

If you enrolled in the class because you were interested in the course content, consider these questions:

1. When was the last time I changed my mind about something important?

2. When was the last time I was wrong about something important and said so to someone I respect?

3. When was the last time I apologized to someone?

4. Do you think people can change?

If you had no trouble answering these questions, you might want to take a course with Burt.

Here are seven more questions for you:

1. Do you like to listen to music?

2. Do you like to read? I mean, a lot? Compulsively?

3. Do you like to watch foreign films with English subtitles?

4. Do you like to be challenged intellectually?

5. Do you like words? And word play?

6. Do you like black and white films?

7. Do you have a good sense of humor?

If you answered "yes" to all seven questions above, we should get along famously.

P.S. I lament the reduction of the research university and education in general to STEM majors, and I think it’s a disgrace students who had to take “The Good Life” were forced to sit through a video talk by former UF President Machen about “following your dreams” however you wish as long as you decide on a stem major in order to "get ahead" and make lots of money. Talk about a captive audience. I prefer the acronym “STEAM,” as in “Science, Technology, Economics, ARTS, and Math.”

In classes, I will ask you to do something you may not have done in any other class, namely, close reading, or slow reading of literature, film, and European or Continental philosophy. I view learning as co-operative. I am a Skeptic, an intellectual.

According to word on the street, some students say I am a somewhat polarizing teacher. Others say I am magnetic, lol. Most students who take my classes like me and say they learn a lot. A few students really do not like me, however. That makes me very sad. I wish they had dropped the class before the end of add/drop and found a teacher they did like. I could say "haters gonna hate" and leave it at that. There's probably nothing I can do or say to prevent some students from taking a class from Burt who just don't like Burt. Like Popeye, I am who I am. (I may have chosen my destiny when I was ten years old.)

But let me try to address what I hear is a commonly made criticism from some student, namely, that my classes "don't have enough structure," explaining myself briefly to you before you decide to take a class with Burt anyway. It's not too late to realize you made a mistake and correct it if you did!

My classes do have structure. Lots and lots of structure. Just check the schedule and requirements pages of my course websites. What students seem to mean by lack of structure is that I do not take authority in the class the way professors almost always do. These students are absolutely correct. In fact, I try to divest myself of whatever authority I have. I do not lecture to students. I do not even always lead discussion. Most of the time, students co-lead discussion. I do not stand or sit at the front of the classroom. I do not pretend to be Socrates. I have students sit in a large circle, not in rows, so we can all see each other. Discussion is not chaotic, and I speak up frequently. It's not as if I abdicate responsibility for class discussion. I demand A LOT of preparation and work from you. But I do not come to class with a specific agenda of powerpoints or takeaway points to present to you. I am something of an anarchist when it comes to method, perhaps an anarchivist. I do insist that we focus on the form of a work--on its structure, on the way a story is told. We will do close reading. Students in my classes have both the opportunity and the responsibility to make the discussion as good as it can be. If you don't want to participate in class discussion, then don't take a class with Burt.

So now let me explain myself a little. I love teaching. I have a sense of humor. I like irony. My approach to literature and film is philosophical. I am more interested in questions than I am in answers. I think you can learn more by taking an oblique approach than you can taking a frontal approach. I like to read difficult books, even books that are possibly unreadable. I like philosophy that is literary. I am fascinated by error, failure, detours, vicious and hermeneutic circles, destinerrant timber trails and paths, telephones, the uncanny in Freud and Heidegger, distraction, lapses, breakdowns and breakthroughs, guilt, parables, noise, silence, Freudian slips, paratexts, incomprehensiblity, stupidity, and losers. I am a bad proofreader. I make lots of typos, and then I fail to find them and correct them. I love puns, word play, especially PARONOMASIA, portmaneau words, and neologisms. I know some French, German, and Italian. I know less Spanish than I would like. I like to travel. I also like donuts. I like to read. I like books. I have over 2,500 in my home. You can check out my library here. (I have no record of my vhs, dvd, and blu-ray library at home and on campus.)

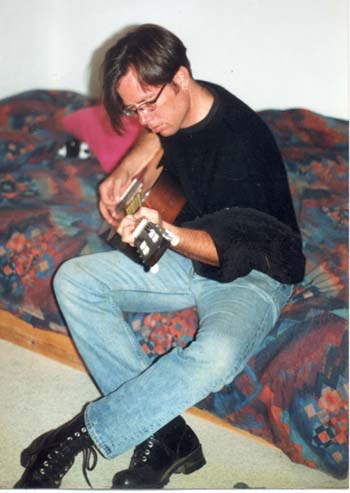

I have been an avid reader and film viewer ever since I was a child. I read all of the stories and poems in the Viking Portable Library of Edgar Allan Poe when I was in third grade. I took philosophy and literature classes as an undergraduate and became very interested in literary theory, especially deconstruction, that questioned the seemingly clear distinction between literature and philosophy. I decided to major in English after taking a British Literature survey class from Janet Adelman. We read--very closely--just Chaucer and Spenser. In graduate school, I was especially interested in the work of Jacques Derrida and Paul de Man. I still am. As a freshman, I took a course on Martin Heidegger's Being and Time and another on the Pre-Socratics. I had started reading works by Karl Marx, Juergen Habermas, Albert Camus, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Jean-Paul Sartre in high school. I read Franz Kafka's The Trial in high school as well (on my own). In college, I read Sigmund Freud's works, again on my own. Since I spend most of my time reading, writing, and watching films, I spend most of my time alone. Wordsworth's "The Solitary Reaper" is one of my favorite poems. I also like Montaigne a lot. In the past twenty years, I have become interested in biopolitics, media storage, media history, media theory, and the work of art. I am also interested in law. My recurrent interests are in unreadability and illegibility. I have also begun work on a course on philosophy (German and French), music, and punctuation. I have a Martin D-35 guitar made in 1971. And I have a Strat made in 1976.

I keep designing new courses that I usually teach only once. The courses I have taught and plan to teach are all linked here. Because my courses are new, I often make minor schedule changes during the semester. I announce any changes well ahead of time in class and by email. But if you like a syllabus that is set in stone, don't take a class with Burt.

Let me repeat myself. I may occasionally call on you, but, like Heidegger, I think the call that conscience places is silent. I do not lecture. I facilitate discussion. I have students sit in a circle so that we can all see each other. I demand that students participate in class discussion. I have students co-lead discussion. I also demand a fair amount of work from you. I will know your name by the third week of class at the latest. I meet with you twice in my office to grade your paper in front of you. I call that "live grading." My classes are structured in some very tight ways and in some very loose ways. I have you write questions about the readings or films before we meet to discuss them. The kinds of questions I want you to ask are highly constrained but they also demand you be creative. Class discussion is exploratory and experimental. I spend a lot of time and energy preparing for each class. But I don't have a specific agenda for each class. As I said above, I don't have "take away points" I want you to learn from each class. I don't use power point. I don't have a method. We learn organically and "anarchivically" in class. We will never finish discussing a text or film; rather, we will have begun a feverish discussion that may never end. I don't believe in coverage, although I do think one should read and learn as much as one can in one lifetime. Nor am I interested in certain kinds of shelving operations such as literary history and biography. By "shelving operations," I mean ways of not reading, ways of closing the book by putting it on the shelf. If you want a master to tell you what to think, you should not take a class from Burt. Learning and messiness are not opposites but mutually constitutive. I do want you to learn how to read or look closely at literature, film, and philosophy. This is my only agenda. Close reading is harder than you may think. According to Paul de Man, no one wants to do it. In a more humorous way, Pierre Bayard asks if we ever talk about books we've read since we forget most of what we've read. I am convinced that slow reading is the same thing as close reading, and I am also interested in far reading, even far out reading. (See David Mikics' overly earnest Slow Reading in a Hurried Age as opposed to Paul North's excellent book Distraction.)

If you want to see the kind of writing I do, you may "look inside" a book I co-wrote that was published in 2013.

One reason I design new courses is that the English Department and other literatures have lost around a third of their faculty since I arrived at UF in 2003: 38 Humanities faculty have left , and three who have been hired have stayed). Some of our grad students now teach upper division courses that should be staffed by faculty. So I try to do several things at once in the same course in order to allow you to make sense of the ways the courses you take can go together. Sometimes I bring in books to show you. I talk about them briefly and pass them around the class.

There are no prerequisites for my classes, but since I teach senior level literature and film courses, I do have several expectations you will have to meet in order to learn: I expect that you know how to how to follow directions, how to write a persuasive essay, have an interest in language, love literature and film, be open to learning new ways of approaching film and literature, and have some basic knowledge of literary criticism and film analysis. This is not an introductory composition class nor is it an introductory literature or film analysis class. If you don't know what a thesis is, what mise-en-scene is, what a shot is, what a dissolve is, what a montage is, what continuity editing is, what an auteur is, how to access UF's online course reserves, how to research peer reviewed journal articles, have never checked a book or journal out of the UF library, rely on google for all your knowledge needs, don't like to analyze literature or films, and don't like to talk in class, then my couses are not for you. And if you are an extremely tidy person who thinks everything has an assigned place and should go in itand stay there, if you don't like messes, then I advise you not to take a class with Burt. However, if you like to read, if you like words, if you are imaginative, if you are intellectual, open-minded, and skeptical, please, by all means, do take a course with me.

If you want to learn more about my teaching philosophy, please go to these pages:

http://users.clas.ufl.edu/burt/teachinglearning.html

http://users.clas.ufl.edu/burt/teachreach.html

http://users.clas.ufl.edu/burt/Nietzsche.html

That's me in Berlin, 1995, when I still had hair. I lived in Berlin from 1995-96. (I had a Fulbright and taught at the Free University and Humboldt University.)

If this text is incomprehensible to anyone and grates on their ears, then the blame as I see it does not necessarily lie with me. It is clear enough, assuming as I assume one has read my earlier writings and done so without sparing the considerable effort; these are in fact not easily accessible. For instance as concerns my Zarathrustra, I will regard no one as its connoisseur who at some time was not deeply wounded and at some time not deeply delighted by its every word: for only then may he enjoy the privilege of reverent participation in the halcyon element out of which it was born, in its sunny brilliance, distance, health, breadth and curiosity. In other cases the aphoristic form presents a difficulty: this is based on the fact that today this form is not taken seriously enough. An aphorism that is properly stamped and poured is not yet "deciphered" just because someone has read it through; on the contrary, its interpretation must begin now, which requires an art of interpretation. In the third treatise of this book I have offered a sample of what I call "interpretation" in such a case:--this treatise is preceded by an aphorism, and the treatise itself is a commentary. Of course one thing above all is necessary in order to practice reading as an art to this extent, a skill that today has been unlearned best of all--which is why more time must pass for my writings to be "readable"--something for which it is almost necessary to be a cow and in any case not a "modern man": rumination . . .

Friedrich Nietzsche,

Sils maria, UPPER ENGADINE,

IN JULY 1887.