|

|

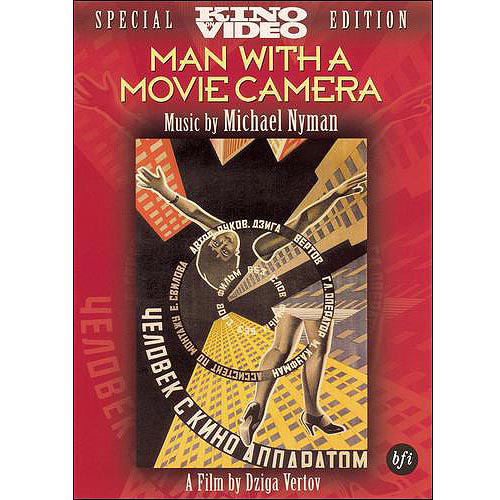

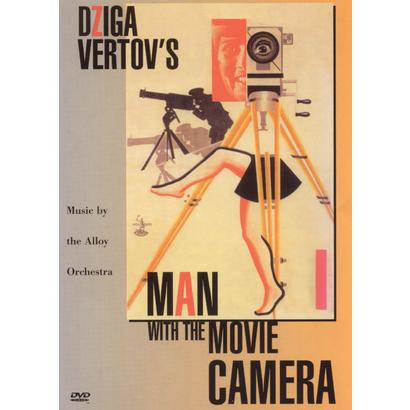

Course Description: Film history is conventionally marked by the development of sound film, or "talkies," in 1927-29, and The Jazz Singer (1927) is widely taken to be the break-through film. Some critical attention has been paid by film historians to the ways in which silent films were never silent but always accompanied either by music or by film-explainers. We will complicate this history, not contest it. We will look at a neglected area of silent film digital restoration, namely, the soundtrack. Many restoration soundtracks have film scores composed for the restoration. Some critics do not like the result. Here is one example of what I call "audioclash":

Here is another example, a review of the blu-ray edition Carl Dreyer's Jeanne d'Arc (1929):

"When Masters of Cinema announced that it would be releasing this new restoration of the film on Blu-Ray and DVD, expectation and anticipation began to flutter. But there was also some concern about the fact that the new release would not feature Richard Einhorn’s beloved score, Voices of Light, found on the Criterion Collection’s Region 1 DVD. So, how do the two scores offered by Masters of Cinema compare?"

Here are a few questions these examples raises: Does this kind of objection have any critical basis? Is there any way to avoid various kinds of audiclash in film restoration? Even if a scores for silent films has not been lost, isn't a digital version with new insturments played by living composers a simulation of the "oriignal" soundtrack? Should all silent film restorations in which have scores that simulate music from the period the film was made? Were music and silent film always "synched," in one standardized manner? What should be done about films that had more than one score? Why do silent film restorers often commission scores that do not simulate contemporary period music, sometimes commission two or more? Can a musician score a silent film soundtrack that is not, however indirectly, founded on sound film musical soundtracks? And should silent film resotration allow for sound effects or even voices in films? What are the criteria for a "good" silent film soundtrack digital restoration?

We will explore these broad questions by looking at a number of particular digital restorations of famous silent films as well examine the use of silence in sound film, and we will look at cases that complicate the conventional history of film, cases in which the same director remade the same silent film as a sound film or added a soundtrack to a silent film and released the film and differnt scores composed for different DVD and blu-ray editions of the same film. To understand the tacit assumptions informing silent film digital soundtracks, we will look at the origins of the soundtrack in the German opera [Gesamtkunstwerk, or "total work of art"] of Richard Wagner and the influence of his method of musical composition on composers who emigrated from Berlin to Hollywood from the 1920s to the 1940s. We will also look at films which use Wagner's orchestral music as their soundtracks. After examining film soundtracks, we will pursue sound design, soundscapes, and so on.

We will gradually attend to various kinds of audioclash that occur even in sound films. We examine the persistence of silent in sound film, the ways in which various directors--from Alfred Hitchcock to Jean-Luc Godard--have called attention to silence in sound film, and in the case of Dogme 95, rejected extra-diegetic music completely. We will also examine the way sound film involves both spoken dialogue and music. Finally, we will pay some attention to intertiles in silent films, simulated intertitles, English translations of intertiles, English substitles in foreign films, lack of subtitles in Hollywood films when languages ohter than English are spoken (Hangmen also Die; Across the Pacific) and dubbing (What's Up Tiger Lily).

Required Readings: Michel Chion, Film, A Sound Art ( 2009); Paolo Cherchi Usai, Silent Cinema, an Introduction (British Film Institute); Theodor Adorno and Hans Eisler, Composing for Films; Theodor Adorno, In Search of Wagner; Paolo Cherchi Usai, Francis, David, Horwath, Alexander, Loebenstein, Michael, ed. Film Curatorship: Museums, Curatorship and the Moving Image; Paolo Cherchi Usai, The Death of Cinema: History, Cultural Memory, and the Digital Dark Age.